Good stuff, kid

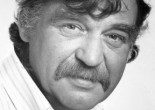

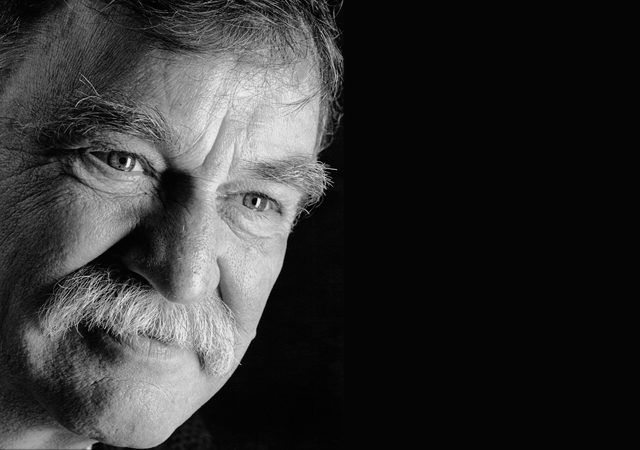

Don Obe reflects on his career and his longtime love affair with New Journalism, which has taken him from Maclean's to Toronto Life to, in 1983, the founding of this magazine.

Don Obe has just learned, after an in-person meeting with Peter C. Newman, that he is going to be an associate editor at Maclean’s. It is early 1972. Since Maclean’s has the same level of prestige in Canada as The New Yorker in the United States, this is big news. Everybody wants to work at Maclean’s because that’s where a writer will be noticed right away. It’s a huge career boost.

For Obe, it’s what he wanted “more than anything,” so he celebrates. After he returns to his home in Toronto’s Moore Park, he gets out a snifter “about the size of a pail,” and fills it with cognac. He puts on a seven-inch vinyl single of Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer” and cranks it loud. He heads to his Eames chair but lands on the footrest. He begins to spin around while singing the lyrics at the top of his lungs. Despite his jubilation, however, he isn’t sure what he is getting himself into at Maclean’s.

Obe is proud to have made it to Maclean’s. He thinks about where he started. Born on March 1, 1936, in Brantford, Ontario, a small industrial town. Mother a mix of British Isles blood, mostly English. Raised five children. Father a full-blooded Mohawk who grew up on the nearby Six Nations reserve. Dad becomes stoker, first class in the Royal Canadian Navy, feeding coal to a frigate’s boiler in the North Atlantic during the Second World War. While Dad is away, Obe shares his first house—a rundown, wooden two-storey place near a dump toward the town’s north end—with his mother, two siblings, two grandparents, an aunt and uncle, and their brood of children. Eventually the family moves to Terrace Hill, a working-class district in Brantford’s core. Obe’s dad returns in 1945 and resumes work as a fitter-welder.

Despite being of mixed native and European blood, Obe is never treated like an outcast. He attends Brantford Collegiate Institute and Vocational School, a little north of Brantford’s Grand Island. Upon graduation, he works two jobs to make enough money to attend the Ryerson Institute of Technology in 1956. He graduates in 1959. In his first year studying practical journalism at Ryerson, Obe learns how to run printing presses and make plates. The embryonic program hasn’t acquired its prestige at this point. “While Carleton and Western would supply the Stars and the Globes, Ryerson would supply the Simcoe Reformers,” Obe says. “It really was the sort of scruffy kid of post-secondary education.”

Obe helped to change that. Over his teaching career from 1983 to 2001, he mentored and inspired numerous journalists. Bertrand Marotte, Quebec business correspondent for The Globe and Mail, was in Obe’s 1984 to 1985 class. He wrote a feature for the second issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism on the quality of news journalism at Citytv, and served as the magazine’s production manager. He says getting positive notes from Obe was “like getting a blessing from the Pope.” Author, editor, and journalism instructor Moira Farr, who was reviews editor of the 1985 RRJ, and has been a contributing editor since the mid-’90s, says, “The fundamentals I have learned—it does all go back to him.”

Now it’s 1972 and Obe is working at Maclean’s under Newman. He may have thought the magazine prestigious, but Newman is a complicated man to work for. Obe has just come out of a story meeting, which was, as usual, a verbal free-for-all. Newman’s agenda for the magazine isn’t sitting well with Obe, and other editors like Walter Stewart are getting into arguments with everybody from writers to editors to Newman.

At the Telegram, Obe met writer and editor Tom Hedley, with whom Obe would be close friends for many years. Hedley at the time was working on Showcase, an entertainment supplement that quickly became well known due to its unique design and the strength of its writers. Hedley says the relationships he made from editing Showcase were thanks to ideas he first bounced off Obe. “Those relationships were key,” he says, “and my very earliest relationship to it all was Don Obe.” Hedley would leave the Tely to become an associate editor at Esquire.

While at the paper, Hedley, Obe, and other writers were amazed and inspired by features published in the magazine under the direction of Harold Hayes, such as Gay Talese’s “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” and Tom Wolfe’s “The Last American Hero Is Junior Johnson. Yes!” These stories, filtered through the sensibility of the writer, redeploying fiction techniques in the service of nonfiction, were proof that good writers no longer had to move to fiction to further their careers. “First, you’d go and work on a newspaper for five years or so and get your speed and work on your style,” says Obe. “And then you’d quit and write the novel. And what we were discovering and pushing, and what I frankly have been pushing my whole editorial life, is that the best journalism can rival the novel, and can be almost on a level of art.”

Now it’s 1972 and Obe is working at Maclean’s under Newman. He may have thought the magazine prestigious, but Newman is a complicated man to work for. Obe has just come out of a story meeting, which was, as usual, a verbal free-for-all. Newman’s agenda for the magazine isn’t sitting well with Obe, and other editors like Walter Stewart are getting into arguments with everybody from writers to editors to Newman.

In his autobiography Here Be Dragons, Newman fondly recalls honing the magazine, which was in dire financial shape, from a monthly into the newsweekly it is today. Those who worked there during those times remember it differently. John Macfarlane, editor of The Walrus, was one of the few staff kept on when Newman took over. “Let’s say it was more of a political environment than many that I’d worked in before and since,” says Macfarlane, who was an associate editor at the time. “People were grinding various axes. People were pursuing agendas.” Author and feature writer Marci McDonald was one of Newman’s first hires. “He had a way of pitting people against each other,” she says. “People would find out that they were doing the same job as someone else, but they were being paid a lot less.” Obe is less civil. “Everybody hated Newman and everybody fought with him. Newman took great pride in this. He thought it was a great atmosphere. Rather than having quiet professionals who did what they were told, he had a bunch of wild men who told him he was full of shit several times a day. I gave him the hardest goddamn time.” This included Obe announcing his resignation several times.

At the same time, Obe respects what Newman was doing. “He would run all these stories, he would assign them to well-known writers. The series was called ‘My Canada!’ Goddamn, it embarrassed us. But he was right. He struck a tone with his economic nationalism that brought the magazine a solid readership and put it back on its feet.”

Now it’s 1976 and Obe is sitting in Club 22, part of the Windsor Arms Hotel, having a beer with Tom Hedley and Robert Markle, the abstract expressionist painter. This is where they’d often go when looking for ideas for stories, and it’s a good place to do that. Musicians, writers, poets, actors, and the like all hang out there. The idea for the Toronto International Film Festival was born there. Also a talented writer, Markle has recently started playing hockey, and he can’t stop talking about it. Suddenly Obe has an idea: “Write me a story and I will get your picture taken at centre ice in Maple Leaf Gardens.”

Now it’s 1976 and Obe is sitting in Club 22, part of the Windsor Arms Hotel, having a beer with Tom Hedley and Robert Markle, the abstract expressionist painter. This is where they’d often go when looking for ideas for stories, and it’s a good place to do that. Musicians, writers, poets, actors, and the like all hang out there. The idea for the Toronto International Film Festival was born there. Also a talented writer, Markle has recently started playing hockey, and he can’t stop talking about it. Suddenly Obe has an idea: “Write me a story and I will get your picture taken at centre ice in Maple Leaf Gardens.”

Two years before this meeting, Obe became editor-in-chief of The Canadian, a weekly roto distributed in newspapers across the country that aimed to encapsulate modern Canadian culture through stories about sports, politics, the arts, and more. It was also the place where he would meet art director Jim Ireland, a designer for the magazine at the time, who became a long-time friend. “You have complete power, as long as you stay within your budget,” says Obe.

With this power, Obe did something unprecedented at The Canadian, publishing a series on Canadian modernist art. Obe loved the Isaacs Gallery, owned by Avrom Isaacs, whose main mission was exposing young Canadian talent. The gallery was right around the corner from the Pilot Tavern, another place Obe and Hedley frequented.

Obe also nurtured writers. He helped Roy MacGregor, whom Obe offered a job once he was at The Canadian. “I was hired as the assistant editor and it sounded like a wonderful job but it was really the lowest job in the entire organization,” MacGregor says of joining Maclean’s in 1973. “I basically just answered the mail that came in from around the country by form letter. Don was one of the people to encourage me to try my hand at an article.” He did, and his first story, about his family history with artist Tom Thomson, got a lot of attention. “Don’s offer was that I come over and be a full-time writer at The Canadian, which I was not at Maclean’s.”

Earl McRae was another writer who improved under Obe’s guidance. Obe saw McRae’s previous sports writing for the magazine as goofy and loud. Obe was planning to fire him, but decided to give him one last chance to write a decent piece. He assigned McRae a story on violence in hockey, centred around Reggie Fleming, an aggressive former NHLer who was finishing off his career in the minor leagues. During every game he was injured by younger players who wanted to prove their grit. McRae returned with a manuscript and handed it to Obe, who immediately called MacGregor to say, “Come up here! You’ve gotta read this.”

“It was wonderful,” Obe recalls. “It may be the best sports story ever written in Canada.” Obe still thinks McRae is one of the top sportswriters Canada has ever produced, and the nine National Magazine Awards nominations for sportswriting he received lend credence to his use of the superlative.

Obe has always had a passion for sports, even though he’s never written about them. During his time at The Canadian, he played on Toronto Life’s softball team, since The Canadian didn’t have one. Sometimes his work and play got mixed up, such as in one near-legendary story. MacGregor was in Winnipeg reporting on a story, but in Toronto a softball playoff game was happening. Obe flew MacGregor to Toronto to play the game, then flew him back to Winnipeg to finish the story.

Being the head of a magazine that put out several features per week—working with talented feature writers such as MacGregor, McRae, and others, with Jim Ireland as art director, plus numerous photographers and illustrators—Obe probably would have stayed at The Canadian forever, but the magazine was losing money. Its owner, Torstar Corporation, brought in marketing experts to make the magazine a more effective ad vehicle. The consultants decided the magazine’s focus should be Canadian heroes. Obe saw the recommendation as a sign to move on: “I’m not gonna stick around and put out a formulaic magazine that celebrates Canadian heroes, thank you very much. So I went toToronto Life.”

Toronto Life would prove to be another challenge. Says Marq de Villiers, who was writing freelance for the magazine at the time, “I remember Obe was hired, he took one kind of horrified look around and put his head down and started to work.” The magazine was suffering after its previous two editors, Hedley and Alexander Ross, who emphasized writing and magazine culture over production deadlines. Issues of Toronto Life under their watch were regularly late to newsstands. “Those guys didn’t give a shit about deadlines,” Obe says. “When you have a magazine that’s full of listings of things to do and it gets to the newsstands after half of those listings had already happened, you’re not going to succeed.” Star writer David Olive, whom Obe hired at Toronto Life, also noted the missed deadlines. “The magazine was still run in a somewhat amateurish way with regards to production,” he says. “That’s the first thing that Don fixed.” Not unlike Clay Felker atNew York magazine, Obe focused on and maintained a deep respect for service journalism. “You’ve got to do that,” continues Olive, “because 90 percent of your readers, that’s what they’re there for. They’re not there for your fancy New Journalism.” Hedley, who directly preceded Obe, occasionally edited the magazine out of a restaurant named Café des Copains on Wellington Street, more or less across from Toronto Life’s Front Street offices. Hedley picked up the habit of editing outside the office during his time at Esquire, on Harold Hayes’s recommendation that editors should be out in the field. That romantic view of editing wasn’t happening under Obe’s watch.

Jocelyn Laurence, who worked as chief copy editor under Obe, remembers his commitment to staying on budget. She dreaded every time she had to tell him that a page needed to be opened, meaning fixing typos at a late stage. Obe would always remind her that it cost money to do that. “So finally I went to him and I said, ‘Well, how much does it cost to open a page?’ I was thinking a couple hundred bucks or something, and he said something like $5,” Laurence says. Obe regretted not having enough money to hire Ian Brown, but worked with plenty of other writers like Carsten Stroud, Philip Marchand, Judith Timson, and Tom Alderman.

Obe quit his editor-in-chief job in 1981 because he missed writing, and began contributing a media column freelance for Toronto Life. One of his columns, “The Dissident Rabbi,” won a 1982 National Magazine Award for religious journalism. “By the time I left, Toronto Life was right on the verge of thriving. And of course it did. It went on to become fat and glossy and no fucking good.”

Obe’s freelancing didn’t last much longer than a year, but during that period he contributed about a dozen media columns and did some editing. Author and freelance writer David Hayes, who picked up the media column after Obe, used his columns as models. Obe’s deep industry knowledge also helped Hayes find sources. “He knew so much about media,” Hayes says. “I’d be talking to him about any media story I was doing.”

Obe had to quit freelancing for two reasons. First, he was rusty as a writer, having mostly been editing for the last decade. And second, his first marriage to author and journalist Sheila Gormley had fallen apart. “I wanted to be as generous as I possibly could be, and I paid off the mortgage,” he says. “I just lost everything. I was just absolutely stone broke.”

Tom Hedley has recently made a couple of hundred thousand dollars from the sale of the script for Flashdance, and he’s invited Obe to come and stay at his place in Malibu. It is early in 1983 and Hedley and Obe are enjoying an extension of their lifestyle in Toronto—frequenting bars, hanging out with writers and poets, and, as Hedley puts it, “living in the period.”

Later that year, Obe sees an ad in the newspaper looking for a new chair of Ryerson’s School of Journalism. He applies and is accepted. The transition from writer and editor to professor isn’t seamless. “For my first class, a three-hour class in magazine writing, I scripted the whole thing. I wrote the whole three-hour talk,” Obe says. “There wasn’t so much as a break for a piss. I just read for three solid hours, scarcely

looking up!”

Now it is September 1983 and Obe, Jim Ireland, and “the Intrepid Eleven,” the nickname for the first RRJ group, are sitting in a converted broom closet, located in the basement of the school of journalism. Nearly everyone smokes. Ashtrays overflow. Obe smokes Winstons. Hanging on the wall are manuscripts and undeveloped photos. Ryerson Polytechnical Institute will soon have its first professional magazine, the Ryerson Review of Journalism, published at the end of the school year, April 1984. “I just loved the idea,” says Ireland of Obe’s new project. “It was something new for Ryerson—something new for me.” Ireland worked on the issue for next to nothing. “Bleak” is how he remembers the early process. “We tried our hardest to make it professional.”

Kit Melamed, features editor on the first issue and now a producer for CBC’s the fifth estate, concurs with Ireland’s assessment. “We had no money,” she says. “We had to scramble to find ways to do things cheap. I do remember driving along Bloor Street—in whose car I don’t know—stopping with Laurie Gillies, the editor, to see if she had indeed found the right, cheapest, and best printer we could find to do the magazine.” Those kinds of adventures were “totally uncharted territory,” and to this day she considers that first magazine production cycle a highlight of her career.

Not only was it hard to build a magazine on a shoestring, but the students had to push themselves to write to Obe’s satisfaction. “The knock was Ryerson students knew how to write a lead but they didn’t know how to think,” he says. “So it was mechanics. I thought of the Review as a way of breaking down that reputation. The stuff had to be written and produced on a level that was highly professional and could not be taken for trade school work.“The thinking in the magazine pieces was on a higher level so that we could break down that bad rep through sheer excellence.”

Drinking has played a role in Obe’s life for most of his journalistic career, occasionally to deleterious effect. “It’s sort of classic, old-timey newspaper guy kind of behaviour,” says Lynn Cunningham, his second wife (and instructor for this issue), from whom he’s been separated for 10 years. “He was by no means unusual. I’m not saying this was a good thing—it wasn’t.”

After retiring from Ryerson in 2001, he decided to quit drinking, checked into the Bellwood Health Centre, and came out sober 21 days later. “I was extremely proud of him,” says David Hayes. However, his drinking resurfaced in 2003. The year before, his only child, from his first marriage, died suddenly at 36. Kira had long been troubled, a runaway at 15, eventually the mother of five children, none of whom she raised for long. The fourth, Andrew, was born in 1990 with fetal alcohol syndrome, and raised from 1992 by Obe and Cunningham, then Cunningham alone. The family attributed Kira’s tragic death to a bad combination of alcohol and codeine, to which she was addicted.

Battles with the bottle weren’t Obe’s only struggles. In 1992, another front opened when he was diagnosed with lung cancer. Fortunately, it was discovered early enough and was operable. He lost a third of one lung, but didn’t require chemotherapy or radiation. He only took a one-semester leave from teaching at Ryerson in fall 1992, a move he later regretted, as he hadn’t fully regained his stamina. And in 1995, yet another front opened, this time a political tilt, when Obe took a strong stand in the so-called Hannon affair at Ryerson. Toward the end of 1995, the Toronto Sun published a sensational story about Toronto writer and Ryerson journalism instructor Gerald Hannon. The Sun’s Heather Bird reminded readers that back in 1977, Hannon had written a Body Politic article entitled “Men Loving Boys Loving Men,” espousing the view that men and boys in some instances could have healthy sexual relationships. Bird was gnashing her teeth for the benefit of right-wing readers, but then she broke the news that Hannon was also working as a male prostitute. Obe was acting chair of the school, and rather than withdraw from the press and wait for the issue to die down, Obe told Hannon to answer any and all questions because there was nothing to be ashamed of. Obe even debated Toronto Star reporter Judy Steed on TVO’s Studio 2; she had tipped Bird to the story originally, and firmly believed that Hannon shouldn’t be allowed to teach at Ryerson. “Defending yourself is one thing, but defending someone else is a lot harder,” says Hannon. “Especially when the issues are so delicate as alleged pedophile support and sex work and all the rest of it—it didn’t seem to daunt Don at all.” Obe’s fight for academic rights, impassioned as it was, still wasn’t enough to convince Ryerson to renew Hannon’s teaching contract.

After the first RRJ issue in 1984, it took little time for the magazine to start winning awards. Many were from the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, and RRJ writers have since won six National Magazine Awards and dozens of AEJMC awards. “When I entered the competition that first time and we won the best magazine award, you can see we were on the way,” says Obe. “Trade school, my ass. Nobody at the University of Missouri journalism school had heard of Ryerson. They sure as hell have now. In fact, they complain that we win too many awards.”

Obe extended his mentoring reach a few years later. In 1989, he became senior editor at the Banff Centre’s Creative Nonfiction and Cultural Journalism program, which he did for 10 years. His “negotiated editing” technique became popular there: rather than rewrite copy, he would make suggestions. That way, writers could take more pride in authorship. One of the writers he nurtured was Moira Farr, who would go on to become a senior editor with the program, now called Literary Journalism.

Others Obe mentored include Erna Paris, whose Banff article became part of her book Long Shadows. Obe had previously worked with Paris at Maclean’s in the early ’70s, where she was hired as an associate editor. “I was completely ignorant about magazine editing and production,” says Paris. “In fact, I can’t imagine why I was hired in the first place! Don was tremendously supportive. I don’t think I could have managed in that environment without his help.”

All of this editing and teaching and coaching began to add up to something dauntingly impressive, and Obe was recognized for his talent by his peers. He proudly shows some of the nomination letters he received when he accepted his 1993 Foundation Award for Outstanding Achievement, which the National Magazine Awards considers its most important annual prize given to one person. There were letters from Robert Fulford, David Olive, Jim Ireland, and many more. Roy MacGregor’s nomination letter included the following: “Personally, I do not write a single sentence without wondering how he would react to it—and this, 14 years after I last worked for him, I know I am not alone.”

Photograph Courtesy of John Reeves

This is a joint byline for the Ryerson Review of Journalism. All content is produced by students in their final year of the graduate or undergraduate program at the Ryerson School of Journalism.

By Michael Thomas

By Michael Thomas