A Wasteland No More

There's a new kind of climate change heating up the nation's newsrooms.Welcome to the Golden Age of environmental journalism. But is it a sustainable development?

It’s another warm, sunny day in late October 2006 and Alanna Mitchell is working in a tiny window-walled office that overlooks her porch in Toronto’s east end. She’s finishing an article for The Walrus, to be published in the winter, about the furious pace of climate change. A framed copy of the mock front page her colleagues gave her when she left The Globe and Mail hangs at the entryway, the headline like a benediction: “Think Globally, Act Globally – The Alanna Mitchell Story.” The strategic communications associate for the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) is doing just that.

Mitchell loves working from home, but it took some adjustment. In 1990, as a new social trends reporter for the Globe, she covered science stories and eventually became the paper’s earth sciences reporter. Until two years ago, she split her time between her home office – neatly filled with science books, papers, childen’s art and work-related memorabilia – and her desk in the Globe newsroom. The routine worked for more than a decade and she reaped recognition. In 2000, Mitchell won the Reuters-iucn Global Media Award for excellence in environmental journalism for “A Special Report From the Vanishing Forests of Madagascar.” Her prize was a fellowship at the University of Oxford. A book deal – resulting in 2004’s Dancing at the Dead Sea: Tracking the World’s Environmental Hotspots – followed.

Despite the acclaim, the equilibrium at the Globe shifted for Mitchell. In July 2002, Edward Greenspon became editor-in-chief. He told staff he believed in beat reporting and he wanted to bring more in-depth coverage and investigative journalism to the paper. However, according to Mitchell, her new boss wasn’t convinced the science of climate change deserved regular coverage and by summer 2004, she says Greenspon had taken her aside and questioned the need for her to be on the earth sciences beat at all. “He told me that he thought I couldn’t write objectively on the subject anymore.” She remembers feeling that “he thought I’d been bought.” Mitchell left in December 2004. (Greenspon’s office did not reply to interview requests for this story.)

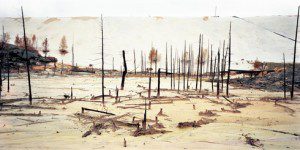

Almost three years later, editorial leaders at the Globe are singing from a different hymn book. In his January 27, 2007 editorial letter, Greenspon acknowledged that the paper had not “fully devoted [itself] into plumbing the depths of the science of global warming, the emerging policies or the economic implications.” He promised that the paper’s “year of going green officially starts today.” And if the masthead’s symbolically emerald background didn’t prove the paper’s devotion, the dramatic photo spread of melting ice caps, monster wildfires, January golfers, ruined fruit crops, snowless skiruns, starving polar bears and Vancouver’s devastated Stanley Park certainly did. “Welcome to the new climate,” read the headline.

Canadian print media hasn’t exactly led the green chorus. In the past two years, best-selling books, award-winning films and celebrityowned Priuses have spotlighted the seriousness of climate change. An Ipsos-Reid poll conducted in October 2006 found that 63 per cent of Canadians were “desperately concerned” that, without major changes, the end is near. CTVglobemedia commissioned its own poll, confirming that 86 per cent of Canadians are serious about environmental action and support higher fuel efficiency standards.

Newspaper executives weren’t the only ones surprised by the public’s newfound concern. In a 2006 Decima Research poll, the environment surpassed health care as the issue voters were most concerned about. And with that, the Conservative government had some re-prioritizing to do. The amount of ridicule heaped on its proposed Clean Air Act in fall 2006 came as a surprise. After Stéphane Dion, draped in lime green, made the environment a key component of his campaign and won the Liberal leadership in December, the government appointed a new environment minister to develop another platform. One month later, a poll showed 11 per cent of respondents were prepared to vote for the Green Party, suggesting it could even win seats in the next federal election.

For the Globe, the era of questioning climate change is over. It has become the new orthodoxy – some critics call it the new religion – and the looming crisis has meant a surge in environmental journalism. During the past six months, the Canadian public has found itself awash in information. Whether this new-found attention is sustainable, or merely another trend based on reader surveys, is debatable. When global warming is no longer polling hot, the media might cool their coverage, just like they did last time.

Climate change didn’t become the hot topic in the Canadian news industry overnight – but almost. Edmonton Journal environment reporter Hanneke Brooymans wonders whether former U.S. vice-president, environmental advocate and Academy Award-winning documentarian Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth was the impetus. The Toronto Star’s national science reporter Peter Calamai speculates that a trickle-down effect occurred when “scientific gobbledygook” started being translated into digestible bits. Martin Mittelstaedt, the Globe’s current environment reporter, rattles off an accumulation of events that together may have built momentum: “Winters without much winter, extreme heat, extreme storms, the Tory attack on climate change policies, the defeat of the Republicans at the U.S. mid-term elections, people repudiating George W. Bush, repudiating a lot of the policies he stood for, more overwhelming science – add those things together and you get a change in people’s views.”

Before the conversion, Mitchell was one of a handful of journalists to cover the science of climate change – but not the first nudged off the beat. Michael Keating wrote some of the first environmental stories in Canada starting in 1966 and later as a reporter for the Globe from 1979 to 1988. Back then, chemical use was the big issue, thanks in part to Rachel Carson’s now canonical Silent Spring, published in 1962. Also an award-winning journalist, Keating was eventually forced out. “They said I was getting stale, to do something else,” he says. “So I jumped ship.” He worked as a freelance writer, a consultant for Environment Canada and a professor at the University of Western Ontario’s Graduate School of Journalism. In the balmy late fall of 2006, Keating recalled a prediction that scientists at Environment Canada made in 1986: “Southern Ontario would have weather like Ohio or Kentucky within about 20 years. We’d have much greater variation in weather, more extremes, more warming in the Arctic,” he says they told him. “It’s all panned out, right on schedule.”

When the United Nations and the World Meteorological Organization formed the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988, the news didn’t cause much of a ripple. Keating admits coverage was difficult then because of the lack of narrative drive. “It falls back on the head of the journalist for not being able to make it a human interest story,” he says. “We might have sold it better to the editors.” The IPCC – a group of hundreds of scientists and policy-makers from around the world – released its first Assessment Report in 1990. The massive document, drawn from mounds of scientific study, concluded that climate change was irrefutably happening.

At the time, plenty of environmental stories ran in newspapers about the dangers of PCBs, the greenhouse effect, acid rain and tree dieback in Canadian forests. The stories may have been an intense wake-up call, but explanations didn’t always look for human causes (“Dinosaur dung provides clue to ancient greenhouse effect” – Kitchener-Waterloo Record, October 23, 1991). Still, environmental coverage was on the upswing to the point that, just after the IPCC released its first report, the Ryerson Review of Journalism’s Maria Smith wondered if we weren’t in an “age of environmental enlightenment.” She wrote in 1990, “But maybe this time concern for the environment will override worries about the bank balance.”

Smith had reason to be optimistic. During the economic boom of the 1980s, editors felt flush and environmental journalism found its place – at least in the margins of the mainstream. But this gradually gave way, especially when the recession of the early 1990s forced editorial budgets to tighten. Then came the Internet frenzy, followed inevitably by the dotcom bust in 2000, the Enron scandal, the freefall of Canadian technology titan Nortel’s stock, Bush vs. Gore and 9/11. It’s no wonder stories about emissions reduction and climate change were scarce.

In 2001, the IPCC released its third Assessment Report (a second came out in 1995). The debate among world scientists focused on what was causing the climate shift. Although the earth does go through natural warming and cooling periods, the panel predicted a spike in global temperatures anywhere from 1.4 to 5.8 degrees. Any change will have enormous impact on the globe – a four-degree shift ended the last Ice Age. The reaction by Canadian news to the report was passing. Most papers posted a story the day of and left it at that. Others – notably the Edmonton Journal, The Vancouver Sun and the Winnipeg Free Press – buried it or didn’t cover it at all. Meanwhile, public debate swirled around the myth potential of global warming, hampered by short attention spans and a lack of familiarity with complex scientific language.

Not anymore. When the IPCC released the findings of its fourth consensus report this February – repeating its previous refrain, with stentorian emphasis – Mittelstaedt said it was “like a five-alarm blaze on the beat.”

T he blaze, which once smoldered deep in A sections, now burns up the front pages, along with charts, graphs and sidebars to break it all down for hungry readers looking for answers. “Science is hard,” Mitchell says. “It’s hard to read, it’s hard to understand and it’s really hard to translate.” Part of the reporter’s job is to sift through mountains of data and jargon, which requires enormous amounts of time and research in order to “democratize the information,” as Mitchell says, and put it into a compelling narrative. This has always been true, but stories once perceived to have been written by advocacy journalists, now focus on searching for solutions to the global warming problem.

At least journalists are no longer expected to play the point-counterpoint game. The days of stories written under the assumption that the reality of climate change is debatable are over. Skeptics were once given equal playing time. “When a child is murdered,” Mitchell says, “we don’t enter into a big social debate about whether it’s appropriate to kill children. We just take it as a given that we don’t want our children to be killed. So we don’t go about interviewing a whole bunch of people who kill children, who want to justify killing children.”

But environmental stories still compete with every other interest. “People crawl over broken glass to get space,” Calamai says. “It’s always a battle to get enough space for articles that go into the complexities.” He also worries that the increase in quantity hasn’t necessarily meant an increase in quality. Some people, he says, “just aren’t checking their numbers against anything but the previous day’s story.”

If the public’s interest is maintained, they’ll be looking for solution-based stories, not just more information. The tendency among many news outlets to shirk conversations about sustainable development business models and in-depth scientific analysis has been noted frequently by frustrated journalists – as well as in media analyses such as The Missing News, a Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives study published in 2000. The authors, while acknowledging the difficulty in reporting on “the byzantine world of research and science,” categorized Canadian coverage of environmental stories as “lacklustre” and guilty of playing up dramatic stories – such as oil spills and radiation leaks – “at the expense of open-ended issues, which are continental and extend over long periods of time.”

A side effect of the climate change conversion is that the science and environmental reporters no longer have exclusive control over their turf. Reporters from other sections are joining the flock. “The Globe has a bunch of interesting environmental reporting, including in the business section, and that’s smart,” Mitchell notes. At the Star, sports reporter Randy Starkman’s story on how climate change affects winter sports (“Melting slopes ‘scary’ sign of climate change,” November 30, 2006) made the front page.

Eventually, if the greening of newspapers continues, stories such as “Fighting for Space at the Mall” – an unquestioning story about the $200,000 Gurkha SUV that makes the Hummer look like a toy, which ran on the front page of the Star’s Wheels section last December – could become a thing of the past. But as long as media outlets publish climate change stories on page one while celebrating trucks the size of tanks in its specialty sections, the new orthodoxy will appear to be a mile wide and only a few inches deep.

While the shift in public opinion became obvious in 2006, not every journalist joined the chorus.

Terence Corcoran’s office at the National Post building in suburban Toronto is lined with books on climate change. Books that support the science, books that refute the science and books that are the science mingle on stuffed and sagging shelves. On his giant L-shaped desk, bright yellow legal-size folders are stacked with their labelled spines facing the centre of the action – Corcoran’s chair. Most of the handwritten labels are slugs for environmental issues – softwood, smog, junk science, tsunami, monsanto. Corcoran leans back in his chair, near a bulletin board covered with signs and stickers such as “Save the World from Greenpeace” and “Proud Member of a Vast Right Wing Conspiracy.”

The Globe’s Margaret Wente and CBC’s Rex Murphy have mocked the rush toward climate change acceptance in the past, and although they both have recently taken a moderated position, Corcoran, editor of The Financial Post and one of its lead columnists, is unrepentant in his disregard for the new orthodoxy. “Junk science” is what he calls the “exaggerated and politicized” data that supports climate change. “I say no to believing in climate change in the same way that, if somebody said, ‘Do you believe in God?’ then I would say, ‘Well, probably no.'”

Corcoran, who in person is courteous and quiet, continues, “I don’t really know and I don’t think anybody else really knows.” Corcoran’s agnosticism – and the conflation of global warming with faith – reached page one of the Saturday Post on February 10. The headline asked readers, “Is environmentalism the new religion?” while the accompanying large illustration showed Gore as a saint holding his good book, An Inconvenient Truth. Belief, skepticism, devotion – the language of faith surrounds climate change, and it’s a phenomenon that annoys Mitchell. “When people say, ‘Do you believe in climate change?’ it’s not like, ‘Do you believe in God?’ It’s not a religion – it’s not even particularly controversial in most parts of the world. This is scientific literature of stuff that’s been observed and printed.”

The Globe’s editor-in-chief agrees. In his public confession, Greenspon assured readers that going green did not mean the paper had “traded in journalist agnosticism for religion… We are in the business of promoting debate, not dogma.” This denial of climate change religiosity didn’t stop either the Globe or the Star from using words and phrases such as “green icon,” “Goracle,” “celeb status,” “climate-crisis hero” and “eco-pilgrims” to report on a February 21 appearance by Gore at the University of Toronto’s Convocation Hall – suggesting, in other words, that this new secular congregation was heralding its prophet.

Back in March 2006, freelance journalist Chris Wood travelled to Mexico City to cover the Fourth World Water Forum, an international gathering of non-governmental organizations, businesses, citizens and governments. On assignment for the Vancouver-based online news outlet The Tyee, Wood highlighted some major points of the event, including the coming water crisis, Canada’s large reserves of fresh water and the role the country will play in the looming calamity. His reports were illuminating, but the editor’s note at the top of his first article was the real shock: “Of 800 international journalists covering the Fourth World Water Forum underway in Mexico City, Chris Wood is the only Canadian.”

That was the original lead of this Review piece, because the anecdote symbolized the state of environmental journalism six months ago. Well, that was then. In the course of reporting for this story – from September 2006 to February 2007 – environmental coverage has shifted from deep skepticism (atheism) to neutrality (agnosticism) to full-blown belief, with all the zealotry that entails.

But we’ve heard this sermon before. What happens if the flock grows tired of repeated oracular warnings? If the current craze for climate change coverage doesn’t hold, Anthony Downs won’t be surprised. Thirty-five years ago, the Brookings Institution-based scholar published his essay, “Up and Down With Ecology: The Issue-Attention Cycle,” which chronicled public interest in ecological and environmental issues. Downs identified five notable stages of interest: pre-problem, alarmed discovery and euphoric enthusiasm, realization of the cost of significant progress, gradual decline of intense public interest and post-problem. In 1972 he noted that during stage three – when “euphoric enthusiasm” about the environment gave way to real concerns – “There is good reason to believe that the bundle of issues called ‘improving the environment’ will also suffer the gradual loss of public attention characteristic of the later stages of the ‘issue-attention cycle.'”

Science and environmental reporters get a lot of ink these days, and that’s good because they have a lot to work with. The coverage is more forceful than in the “environmental enlightenment” era of the late ’80s and early ’90s – and looks better too. Large-scale catastrophes such as the December 2006 windstorm that ripped Stanley Park to pieces make for excellent visual enhancements. Even less immediate events can now be portrayed vividly: photographs depicting the glacial Alps 45 years ago and today, placed side by side, are splashes of cold water to accompany a story on glacial melting.

But the real test for journalists will be to keep the story going when the weather is benign, when the political winds shift and when the next commissioned poll says public interest in climate change has waned.