Crewless

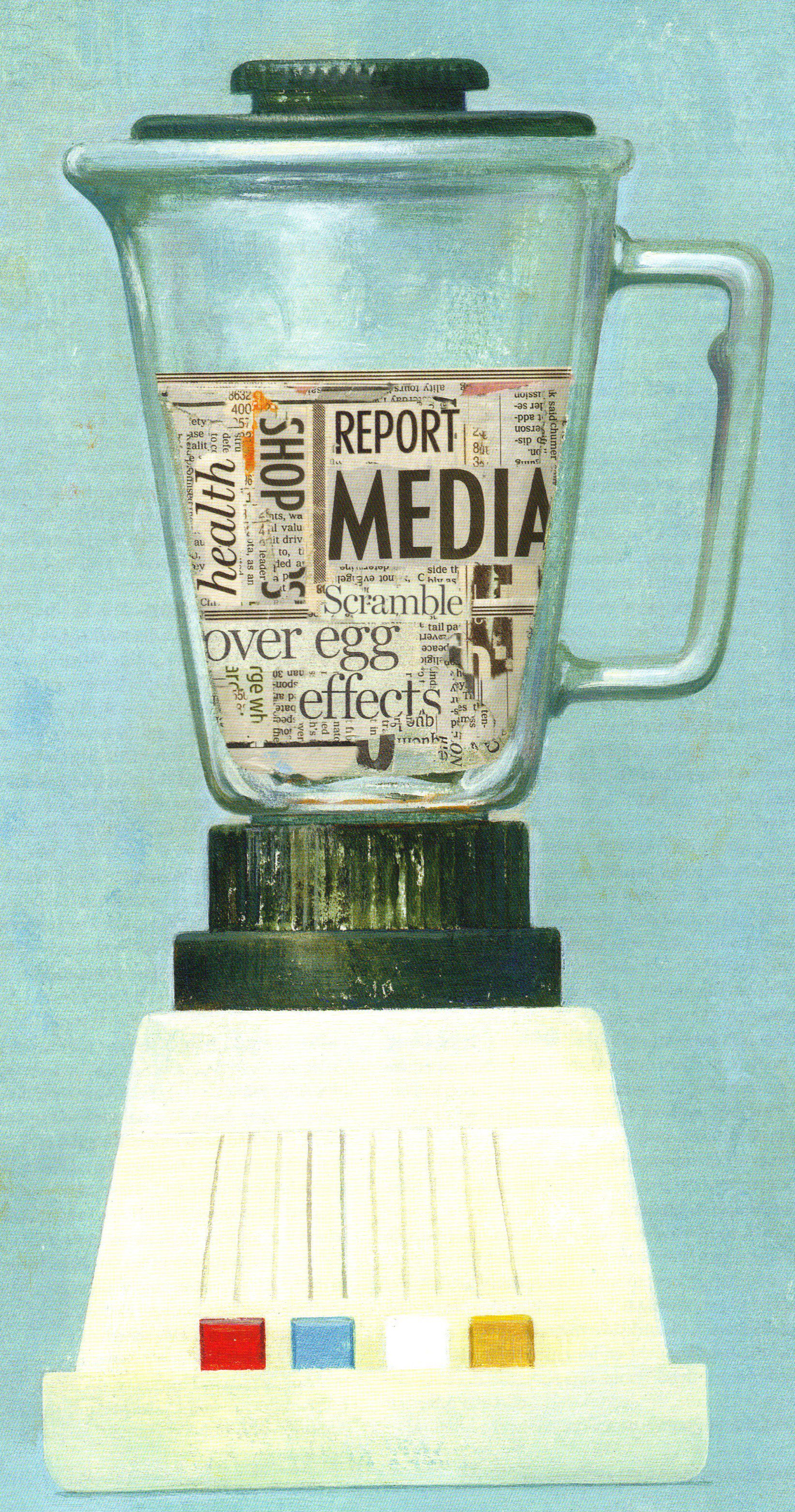

Cheaper, faster and better: Working solo, video journalists are infiltrating TV news. Everywhere

It’s hockey night in Windsor and the hometown’s Spitfires are hosting the Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds in a Monday night battle at Windsor Arena. Nine rows above ice level, Scott Scantlebury is looking through the viewfinder of his Canon Hi-8 video camera. He could be the proud father of a player filming a home movie of the game, but in fact he’s a sportscaster and video journalist, or VJ, for CBET, the CBC’s Windsor station, on assignment for The Windsor Late News. Beside him stands the two-man crew from Baton Broadcasting, a reporter and a camera operator toting a Sony Betacam three times the size of Scantlebury’s Hi-8.

Ice level action is furious-a fight, a penalty-but no goals yet. Scantlebury can only stay for the first period-he’s got to get back to the station and put his sportscast together-and he’s counting on at least one goal to use as a highlight in his report. He picks up his camera and moves in behind the Greyhounds’ net-if the Spits score, he’ll have the best angle on the goal. The BBS crew stays put. The first period is half over when Scantlebury hurries back to his original position and rummages through the gym bag holding his extra equipment.

“My battery went dead. You should always carry a couple with you,” he explains as he shoves a new battery into his camera. He’s rushing back to his spot behind the Greyhounds’ net, camera in hand, when the Spits score. Scantlebury’s shoulders sag. He looks back at the BBS crew-still filming-and shrugs. There aren’t any more goals in the first period so he heads back to the station without the footage he needs.

For opponents of the VJ approach to news gathering, Scantlebury’s experience illustrates all that is wrong with the one-man-band method of television reporting.

Traditionally, most TV news was-and still is-covered by crews of two, three or four people: a reporter, a sound technician, a camera operator and maybe a field producer. VJs can get the story alone. While many television executives love VJs because they’re cheap, Cameron Bell, the former news director at BCTV, toldThe Vancouver Sun last spring, “The assumption that a guy can be a good cinematographer and a good reporter is debatable.” He thinks that some reporters could make the transition to shooting their own stories, but some could not. As critics argue, a reporter can get either great pictures or great interviews but never both. The technological responsibilities of the job distract the VJ from the story and the quality of the journalism suffers. That’s one reason VJs aren’t common in Canada; another reason is the unions.

Powerful unions like CEP-NABET and the Canadian Media Guild are worried, understandably, that if work done by a three-person crew can be done just as effectively by a VJ, a lot of camera operators and broadcast journalists may lose their jobs. Still, even the most ardent union supporters concede that video journalism is a rapidly growing part of broadcast journalism.

It’s like Kim Kristy, a VJ colleague of Scott Scantlebury’s, says: “It’s a natural evolution of what television is all about.” A lot of Kristy’s colleagues agree with this assessment. Among them is Nancy Durham.

Durham is a CBC foreign correspondent based in London, England. She’s worked as a traditional TV reporter for three years and toiled as a radio journalist for six years before that. Almost two years ago she started going on assignments by herself with a Hi-8 camera. One day in Sarajevo she walked right into the bathroom with a Bosnian woman. Durham aimed her Sony Hi-8 and filmed the woman putting on makeup by candlelight because the electricity was off. Later she recorded as the woman took water out of her bathtub, cup by cup, to fill her washing machine. And when the power finally came on for an hour, Durham filmed the woman rushing down her stairs to do a load of laundry.

“Journalism is more and more packaged and that’s another reason why this Hi-8 video journalism is a kind of salvation,” says Durham, who hates attending press conferences or doing prepackaged stories. “Its cheap, you can go out and gather yourself, get your own angle on a story.”

Foreign correpondent VJs like Durham go into war zones, they travel into restricted areas and they find the hidden story not despite being alond but because they’re alone. “You can get really intimate with people, into intimate places,” says Durham. “I don’t think you could do that with a crew.” There’s no way, for example, she could have crawled into a haywagon with Serbian refugees, as she did last fall. But by herself she traveled with the two women, capturing their journey to safety across the war-scarred landscape of the former Yugoslavia.

Durham’s only been a VJ for a couple of years, not like Sue Lloyd-Roberts, whom Durham describes as a pioneer of investigative video journalism. Lloyd-Roberts of the BBC began working as a VJ in the mid-eighties and in the spring of 1994 she hid a video camera in her bag and got the first footage ever shot in a Chinese forced labor camp. She’s been to Burma, Australia, the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and Iraq getting items conventional television news crews could never do. Last fall,she went to Eastern Europe for an investigative story on prostitutes during which she filmed the longest line of hookers ever, 400 standing shoulder to shoulder. She didn’t bring a camera operator and a sound technician with her. “They’d simply be lynched by the pimps, but it’s the type of thing you can film if you’ve got a small Hi-8 camera and a passing car.”

Of course, the solo television reporter has existed for years. Eccentric freelancers took their cameras to faraway lands, where they filmed, wrote and edited stories on their own. But these early VJs were rare and it wasn’t until the early eighties, when Toronto’s CityTV introduced its “videographers,” that new possibilities became apparent. While City’s VJs were mostly assigned to smaller feature stories, outside Canada the wider use of video journalists grew. In 1989 the world’s first all-VJ station opened in Bergen, Norway. Three years later, New York City became the home of New York 1, a 24-hour cable news station that armed its reporters with Hi-8 cameras and told them to cover North America’s biggest city. NY 1 has spawned copy-cat cable stations in Chicago, Washington, San Francisco as well as in England.

Will video journalism ever replace conventional news-gathering methods on daily news broadcasts? Norm Bolen, now the CBC’s head of TV news and current affairs, doesn’t believe so. “You can think of all kinds of situations where you’d probably want another set of hands,” he says. “It’s no panacea; you’re not going to immediately convert all national reporters into video journalists.” Dennis MacIntosh, a senior producer at CTV News, concedes that video journalism is a growing trend. But VJs haven’t come to CTV’s national news yet. “You get more pictures and better quality the more people you send out,” he explains.

Skeptics concede that VJs are useful for soft feature stories but question their ability to go out and get the breaking news day in and day out. The CBC decided to test the limits of video journalism and embarked on a two-year project that has been dubbed “The Windsor Experiment.”

In December 1990, CBC budget cuts led to the closing of Windsor’s TV station. Nearly 90 people lost their jobs and CBET took a station break that lasted more than three years. But on October 3, 1994 at 5:30 p.m.,The Windsor Evening News returned to channel nine in a slick new format driven by video journalists.

Norm Bolen, the CBC’s Ontario regional director at the time the station was resurrected, says that some CBC managers “thought that by doing an experiment in Windsor with new technology, new workplace methods, they might be able to bring in a budget and make it saleable to head office and get it back on the air.” Well, head office liked the idea it was necessary to convince the powerful, established unions in the CBC that allowing a reporter to pick up a camera wouldn’t put union jobs across the country in jeopardy. The Canadian Media Guild represents 3,500 CBC reporters and producers and CEP-NABET represents 2,500 technical employees like camera operators and editors. Mike Sullivan is a CEP-NABET repesentative who was heavily involved in drafting the agreement that put Windsor back on the air. “Early on in the negotiations we said let’s not get into video journalism in a big way, let’s just see if we can put Windsor on the air much smaller,” he recalls. Management insisted on using VJs and eventually the unions came on board. “So with some trepidation about the precend it might set, we sat down and worked out an experiment,” says Sullivan.

“The Windsor Agreement” allows reporters to use cameras, allows camera operators to do the work of reporters and makes it possible for fewer than 30 people to put together Windsor’s daily television news. There are now 10 VJs at the Windsor CBC. Five have technical backgrounds as camera operators or editors and five used to be reporters. Throughout the negotiations leading up to the Windsor agreement, both the unions and management agreed on one very important thing. As Sullivan says: “Whether it was an experiment or not, the CBC’s journalism had to remain the best there is.”

To achieve this. Cynthia Reyes, a top CBC trainer, was called on to whip everyone in Windsor into shape and to insure the maintenance of high journalistic standards. She studied the work of video journalists from around the world and designed a six-week program to teach camera operators how to report and reporters how to shoot. Although not everyone at the station is a VJ, every employee at CBET took part in the workshop. On October 3, 1994, Reyes sat back to see if “The Windsor Experiment” would work. It did.

“For me it was a combination of relief-that we actually had a professional-looking show-and a delight,” she recalls. Part of the training involved erasing any prejudices that reporters might feel toward camera operators and editors. “We greatly underestimated the talent and ability of our so-called technical people,” says Reyes. “I never refer to them as technical people, I always call them journalists.”

After nearly a year and a half on the air, the VJs at CBET reflect on the things they’ve learned. One lesson is that a VJ can do a whole lot but there are stories where more than one person is needed. “I think that people are embracing this as an answer to everything,” says Windsor VJ Pat Jeflyn. “It’s a mistake because sometimes you need three people. I mean, if the story’s really big, if there’s a lot of hostility involved, if there’s a lot of digging investigation, if there’s a lot of really tough technical work to be done or a lot of tough information to be dug out, you need two people.” The Windor VJs agree that press conferences, court stories, large symposiums and dangerous stories are best covered by two or three people.

But Jeflyn is quick to add that for many stories one person is ideal. She recalls her interview with an incest survivor who was very relieved not to face a room full of cameras, bright lights and people. He relaxed when he saw that Jeflyn was alone and it made for a better story.

Jeflyn, whos worked in both TV and radio, says she’s often asked if a VJ can produce good work: “I think if you’re a good journalist and you believe in what you’re doing, you’re going to keep the quality. I wouldn’t do it if I couldn’t.” Windsor VJs have proven themselves in the field?-former reporter Kim Kristy has sold footage to American companies, and one-time camera operators like Brett Morrison have become solid reporters.

Morrison doesn’t have any trouble shooting a story, but admits he agonizes over his script and, because he’s a little shy, he still often feels uncomfortable during his interviews.

Physical strain is also a factor, especially in Windsor, where all but two of the VJs use 20-pound Sony Betacams. A Windsor VJ carries a camera and a tripod-close to 50 pounds of equipment. Lighting equipment is extra. Jeflyn embarked on a weight-training program at the local Y to prepare herself for the physical rigours of her job and she and Kristy admit that there are days when they’re just too exhausted to move.

Only the confidence that comes with experience will help Brett Morrison and other VJs who find themselves learning new skills, but advances in technology are making it possible for VJs to use lighter equipment without losing very much sound or picture quality. Sue Lloyd-Roberts uses a Hi-8 and though she admits her pictures might not meet the high standards of the BBC’s technicians, viewers don’t complain. In fact, Hi-8 cameras produce pictures that are virtually indistinguishable from those shot on top-of-the line Betacams. And a Hi-8 is cheap, about one-third the price of a Betacam.

The sound recorded on a Hi-8 is excellent. “I sell the audio from my camera to the BBC,” says Nancy Durham, who adds that the technicians at BBC radio “nearly flip” when she tells them she’s managed to get such good sound with a little Hi-8.

The cameras are also user-friendly. Durham, having never touched a camera before, needed only two days of intensive training before she was ready to shoot pictures for the CBC’s national news.

Durham and the VJs in Windsor agree that their brand of journalism is going to become increasingly popular. In the very near future news directors are going to be looking for reporters who know how to use a camera. A number of journalism schools are preparing their students for this inevitability. Mel Tsuji teaches “videography” at Toronto’s Humber College. Tsuji’s course gives students the journalistic roots needed to be professional VJs. He stresses that the most important facet of the VJ’s job is journalism. “I think the prime condition of it is you have to be able to write a story,” he says. Tsuji’s been teaching the course for three years and a handful of his students have graduated and are already working as VJs. The course was created to help students adapt to “the changing nature of the business.”

Humber College is not alone in offering an education in video journalism. In 1992 Columbia University in New York City spent $75,000 on new equipment, including 10 Hi-8 cameras, and is credited with establishing the world’s first course in video journalism. Northwestern University, just outside Chicago, spent over $600,000 buying nine Hi-8s and upgrading its facilities in the early nineties to prepare its graduates for the new jobs in journalism.

Obviously, many journalism schools agree that VJs are a growing part of broadcast news. Sure, the work done by VJs will be criticized, but it’s like Paul Sagan, vice president of news and programming for NY 1 says: “I’d sympathize with the critics the way I’d sympathize with the owner of a buggy-whip factory who just looked out the window and saw a Model-T drive by.”