Developing from the Negative

Forced out of shrinking newsrooms, photojournalists are going rogue to keep their craft alive

When Louie Palu left The Globe and Mail in 2007, his plan was to pursue personal documentary projects. He spent four years alongside Canadian and American military units in Kandahar, Afghanistan. The News Photographers Association of Canada named him Canadian Photojournalist of the Year in 2008. In 2011, he went to Mexico on a fellowship from the New America Foundation. For more than a year, he travelled along the U.S. border photographing members of organized crime groups, victims of gruesome gun violence and the drug-addicted.

As a freelancer, Palu is not bound by third-party deadlines and has built up a body of work that ranges from portraits to spot news. Inspired by the work of photographer Will Steacy, Palu imagined his own concept newspaper. He wanted to publish his work with minimal text and without advertising—a paper dedicated entirely to images.

Funded by his fellowship, Palu created Mira Mexico, or See Mexico, in 2013. Sixteen full-sized images on eight 11.5-by-15- inch pages depict quotidian life in Mexico on one side and the dark underbelly of the drug war on the other. Visually striking, Mira Mexico’s loose-leaf format allows readers to do their own editing by reordering and folding the photographs to create different perspectives.

Several publications, including the Globe and The Atlantic, picked up some of the images. Had he been working for one of these deadline-driven organizations, it’s unlikely that Palu would have been able to embark on such a long-term project. Now, more freelancers are following his lead. Budget cuts and an emphasis on multimedia have pushed many staff photographers out the door, but not necessarily to the fringes. Freelancers like Palu are creating personal projects that challenge the boundaries between journalism and art. Their creative approach to the craft is evolving from the traditional idea of photojournalism and reasserting the value of the still image.

When the Chicago Sun-Times gutted its entire photography department in 2013, the paper gave its reporters a training session on iPhone photography basics. It was an attempt to make up for the loss of nearly 30 staff photojournalists. “Chicago Sun-Times-ing” became a term that could be used to describe similar cutbacks in the industry.

Almost a year later, the Globe liquidated its own photo department, save for two senior staffers: John Lehmann, based in Vancouver, and Fred Lum in Toronto. It replaced the laid-off photographers with freelancers, including at least two former staffers. Now, the only difference in their job description is that the Globe no longer pays them an hourly wage, nor does it provide health benefits or give them company gear.

In March 2015, Brunswick News decided to “Chicago Sun-Times” the photo departments of its daily newspapers. Several people lost their jobs, including three from Moncton’s Times and Transcript, two from Saint John’s Telegraph-Journal and one from Fredericton’s The Daily Gleaner. Regional general manager Jean-Claude D’Amours said the move was “in line with our long-term strategy of digital transition” and that it would help the company adjust to a “new technological reality.”

Listen: Ian Willms, co-founder of the Boreal Collective, describes what’s lost when newspapers replace their photo departments with iPhone-wielding reporters

Hiring freelancers instead of employing full-time photo staff is more expensive on a daily basis, according to Globe photo editor Moe Doiron, but it’s cheaper in the long run. A freelancer for the paper typically makes about $200 to $300 per assignment (which, Doiron says, is above the average industry rate). But after factoring in salary, set work hours and company-provided gear, the average staff photographer costs more per week than a freelancer.

The call for digital transition and the infatuation with the multimedia journalist has been a decades-long obsession. In 1997, American photojournalist Dirck Halstead developed the “Platypus Theory” to describe the push for photographers to venture into videography.

Upon its discovery in the late 18th century, the platypus caused an uproar in the zoological community because it couldn’t be categorized. It wasn’t really a bird or, strictly speaking, a mammal—it was a hybrid. The multimedia journalist is a platypus, expected to be equally skilled in all aspects of journalism: audio, video, photography and writing.

In recent years, this push has become more of a shove. Even before the launch of the Star Touch tablet app, Taras Slawnych, visuals editor at the Toronto Star, stipulated that photographers applying to the paper should submit a short video to demonstrate their proficiency as videographers. Similarly, Doiron won’t look twice at a resume if it doesn’t mention multimedia skills. South of the border, the Sun-Times rehired four former photojournalists as multimedia journalists.

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag writes, “Nonstop imagery (television, streaming video, movies) is our surround, but when it comes to remembering, the photograph has the deeper bite.” Though Slawnych doesn’t deny the power of the photograph, he says the emphasis on video has one primary motivator: money. The decline in advertising makes revenue from print harder to come by, and digital advertising is even less lucrative. Not everyone clicks on banner ads, and paywalls can deter readers. But those annoying video ads that run before news pieces are an effective way of cashing in digitally. According to a 2014 Pew Research study, videos account for more than a quarter of all display ad spending. And it’s difficult to put a commercial in front of a photo.

Technically speaking, high-quality video and photography have never been so easy to produce or share—nor so affordable. Since Apple unveiled the first iPhone in 2007, the phone has become one of the world’s more recognizable mobile technologies—approximately 101 million iPhones were used in the U.S. in 2015 alone. The camera quality of the latest version, the iPhone 6S, is comparable to the Nikon D3 camera, which was hailed as “state-of-the-art” and sold for $5,499 when it was released in 2007. The iPhone 6S retails from $899 to $1,029. For Android fans, the Samsung Galaxy S6 camera is also comparable to a DSLR and is even cheaper—ranging from $699 to $969. In a field that seems forever in decline, reporters armed with accessible, user-friendly smartphones are an enticing alternative to the traditional—and now largely defunct—photo department.

Annie Sakkab has displayed her work on the walls of trailer homes in Dubai, at the Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival in Toronto and in the pages of Canadian newspapers. Her formal training in photography helps her tell stories in a compelling way. Photos courtesy of Annie Sakkab

Annie Sakkab took the long road to photojournalism. At 16, she received her first camera from her brother when she went to the U.K. to study fine art. After realizing she couldn’t make a living as an artist, she went back to school and became a graphic designer. Then, in 2008, while taking a photography workshop, she travelled to a work camp in Dubai. There, she documented the lives of over 3,000 migrant workers. “Doing that project was when it really hit me, what photography is all about,” she says.

The same year, she moved to Toronto to pursue a new career in documentary photography.

In 2010, Sakkab returned to the camp with the intention of showing her photographs to the workers. When she arrived, she found that only 35 or so of the previous tenants remained—most of the others had moved elsewhere.

With such a small audience, she decided the most effective way to show the images was to project them onto the workers’ trailer homes. She also documented their reactions and exhibited the resulting collection of photographs in a group show, entitled Dislocations, at the 2013 Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival in Toronto.

Art and photojournalism have always been linked. Before the introduction of the camera in the mid-19th century, historical and socially significant events were documented through paintings or etchings. Scholars describe Goya’s The Disasters of War, a collection of etchings depicting the atrocities of battle, as an ancestor of modern conflict photography. The daguerreotype process was developed in 1839; nearly 15 years later, the first war photographs were taken during the Crimean War and would later be exhibited.

Palu says this historical intertwining is important. Art is about conveying a message in an accessible way, while the means of conveying it—through painting, sculpture, sketching—is an exclusive talent. Though anyone can hold a brush, not everyone can paint a masterpiece.

The same is true of photojournalism. While the technology is readily available, the ability to visually convey a message effectively is something that comes with time, experience and extensive training. “What distinguishes the pictures I take on an iPhone over a reporter’s is, obviously, skill,” Lehmann says. “I would like to think that you could put any tool in my hand and I will do a good job with it.”

A study conducted in 2014 by the National Press Photographers Association tracked the eye movements of participants, who were presented with 100 photographs taken by professional photographers and 100 photos submitted to newspapers by the general public. The results showed that people could differentiate between professional and amateur photographs 90 percent of the time.

Nearly all the study’s participants mentioned the importance of storytelling. One man said that if he were running a newspaper, quality images would be a top priority rather than, as he put it, “Everyone just kind of sent stuff in.” Newspapers that employ freelancers are at least maintaining the quality that untrained, or undertrained, reporters with smartphones can’t quite match. After graduating in April 2015 with a photojournalism degree from Loyalist College in Belleville, Ontario, Sakkab had a brief stint at the Waterloo Region Record before leaving for Jordan, her home country, to cover the refugee crisis as a freelancer for the Globe. She says her fine art training influences her work, but she doesn’t believe an art-based approach is exclusively hers. She says the idea that photojournalists can’t be artists simply isn’t true, and that the two are, in fact, inseparable.

The attention to composition, the consideration of lines and space, the intentionality of the image and the anticipation of how the image will be published are all foundational art practices. She also says this gives her and her colleagues an edge over their iPhone-wielding competitors. “As a photographer, everything around you, everything you see, everything you’ve been told culminates in that moment when you take that one picture,” she says. And all of that is lost when untrained reporters shoot pictures with their iPhones. “They just take it, then they’re gone.”

In the weeks leading up to last October’s federal election, the outcome was still anyone’s guess. Support for Stephen Harper’s Conservatives remained strong, and it seemed entirely plausible that the party’s near-10-year reign could, and would, continue.

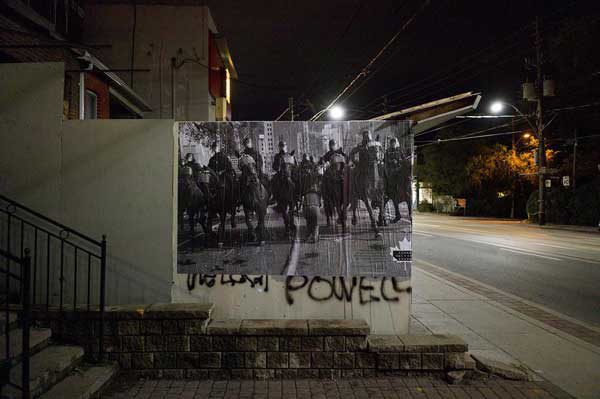

The Boreal Collective took its photos to the streets with Canada Has Changed, its politically minded wheat-pasting campaign. As newspaper photo departments dwindle, photojournalists are free to start their own creative, independent projects and initiatives. Photos courtesy of Ian Williams/Boreal Collective

Laurence Butet-Roch is a member of the Boreal Collective, a group of international photojournalists whose mandate is to “inspire greater creative and social consciousness at a time when the photographic industry is being dismantled.” Even before she joined the Collective, her work as a freelance photographer and staff photo editor for the French magazine Polka promoted what fellow members have dubbed “artful journalism.” She also launched the Canada Has Changed wheat-pasting campaign, inspired by the #Dysturb initiative that originated in France.

Under the cover of darkness—armed with rolls of large-scale images and a homemade paste made of flour and water—the artists wheat-pasted walls around Toronto and Montreal. The gooey, starchy mixture dripped off the rollers and down their sleeves. It pooled in the elbows of their shirts as they criss-crossed each city, plastering construction boards and covering old concert posters. Each image was split into three segments that, when pasted side by side, revealed a black and white print, measuring three- to four-feet wide and up to five-feet high. One showed children playing baseball in Aamjiwnaang, Ontario, with a synthetic rubber plant looming in the background. Another was an aerial shot of the Alberta tar sands. Yet another showed someone nearly being trampled by mounted police during the 2010 G20 protests in Toronto. For weeks: align, roll, paste, repeat. Don’t stop until something runs out.

The French #Dysturb campaign was apolitical. But Butet-Roch thought Canada Has Changed should be the opposite. The project’s six images addressed issues that either originated from, or were exacerbated by, legislation passed by the Conservative government. There was no advertising and minimal text, save for a small caption giving each photo context. “The idea,” says Butet-Roch, “was to let people know what Canada was like today.”

Ian Willms, co-founder of the Boreal Collective, says being a small, independent enterprise allows the group to take on big, creative projects. “The overhead is next to nothing, so when we see an idea we like that requires us to change, we can do that, which is something that larger newspapers or magazines can’t do,” he says. “We’re small, we’re loose and we’re willing to try new things.”

At 30, Willms is already an established photojournalist and regular contributor to The New York Times. His photographs have been shown in Canadian, American and European galleries. But in 2010, he began to steer away from the institution that had garnered him so much success.

Unsatisfied with the photographs published in newspapers and on the pages of glossy magazines, Willms and a handful of other photographers founded the Collective. The details are fuzzy, but Willms recalls that the idea was conceived in a car, lubricated by marijuana and the comfort felt among friends.

Since its inception, the Collective has grown to include 12 photographers. On top of group projects, they curate exhibitions and hold educational workshops. For the past three years, it has hosted the Boreal Bash, an event that includes gallery exhibitions, portfolio reviews and guest speakers, including renowned photojournalist Larry Towell.

Willms, Sakkab and Palu all agree that it’s often tough to make a living as a freelancer, but the creative freedom is worth it. That’s why Doiron doesn’t consider the decrease in staff jobs or the rise of multimedia journalism to be the death of still photography. Pros who aren’t, as he says, “pegged on the idea of getting money” give him a wider range of style and content to choose from. “It’s almost like photojournalism is going back to a fine art vocation and less of a ‘hired gun,’” Doiron says. With newspapers like his becoming increasingly dependent on freelancers for images, a creative spin on the traditional is a welcome change. There’s a resurgence of the values photojournalism was originally built on. These photojournalists are creating work for its own importance and for society’s benefit—and it’s about time.

Allison Baker is the multimedia editor for the Spring 2016 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.