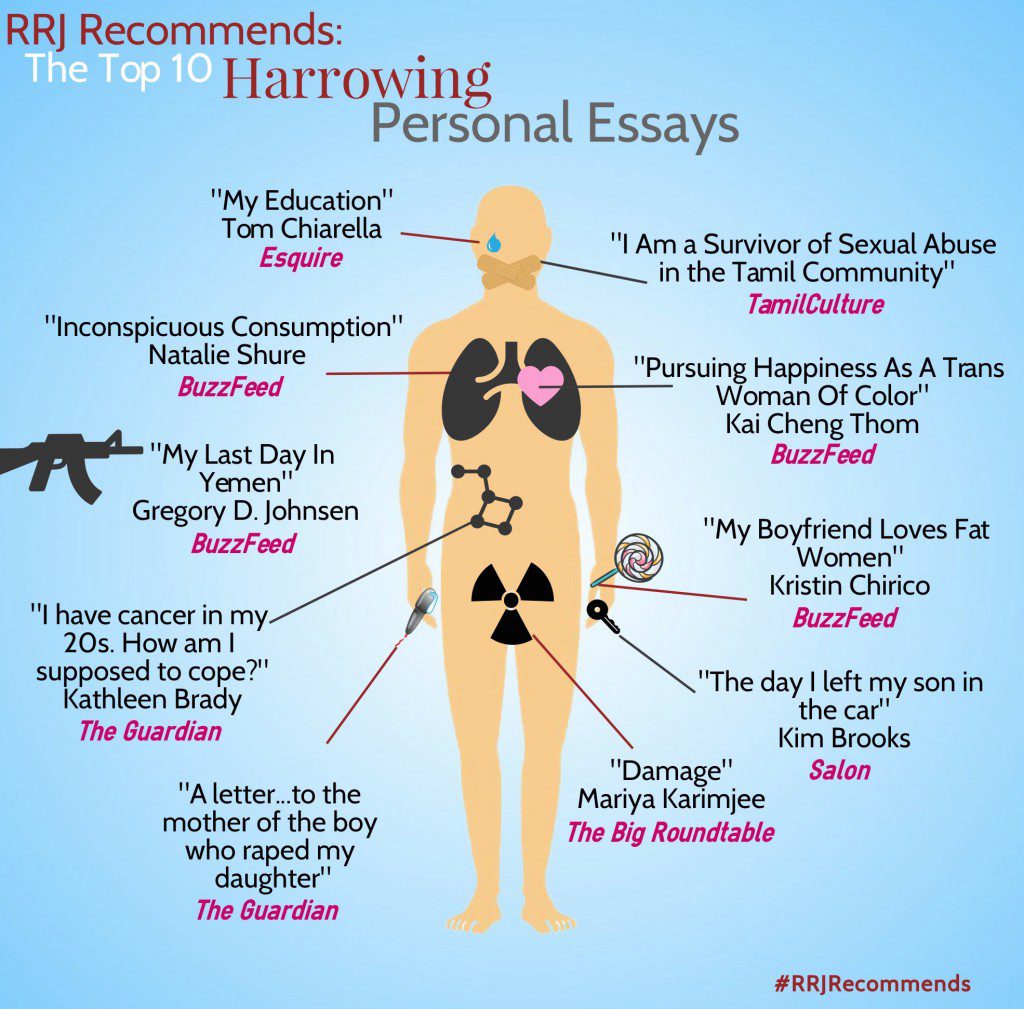

Everybody’s Got a Story that’ll Break Your Heart

First-person journalism can bring out the critics, but that hasn’t stopped online publications from using it as a powerful tool to connect with readers

Leigh Stein’s boyfriend Jason threw her against the refrigerator and didn’t believe she was hurt until she showed him the bruises. They had moved to New Mexico together so she could write her book while he worked—it was the most romantic plan she had ever heard. She recounted her relationship in a BuzzFeed story about how she investigated Jason’s arrest for a stabbing incident 11 days before his death in a motorcycle accident. “I thought I’d be able to draw a clear, straight line between our visit, his crime and the accident,” she wrote, “and then the story of our lives together would finally make sense.” In the comments section, many women shared their own stories of abuse.

Stein’s story is evidence that personal journalism, which is increasingly accessible online, allows writers to explore important topics such as mental health and domestic violence in a way that has a powerful effect on readers. They’re like getting hooked on someone else’s pain. While critics of first-person narratives say they are self-indulgent and get published only when they tell a painful story, the articles resonate with readers.

Personal journalism has always been around, says BuzzFeed Canada’s Lauren Strapagiel, but the difference now is that there is so much more content out there—people can always find an experience that speaks to them. “People are going to ask for it and go looking for it, and people are going to write to meet that need.”

In an August Vice story about surviving Hurricane Katrina and living with the guilt, Megan Koester took readers through her evacuation to the present, describing how lucky she is compared to those who didn’t escape. A January piece on The Huffington Post blog by Abby King was written in the form of an apology to her children for divorcing their father: “I will forever feel guilty that we broke your home and world apart.”

These articles give readers going through the same experiences validation by showing that other people feel the same way. “On a fundamental level, we connect with stories that have a strong human component,” says Craig Silverman, Buzzfeed Canada’s editor. “From a strategic perspective, first-person stories can do well online—people share them if it’s an experience that they can relate to.”

The Huffington Post opened a Canadian office in 2011, and blog, which publishes many first-person pieces, now has 5,000 contributors. Blogs editor Sadiya Ansari says the posts contribute to the public conversation from the perspective of an individual. Although personal narratives are found most notably on the Living and Parents pages, they are in every section—even on the Business page. A tale of a woman’s miscarriage on Huffpost Parents attracted a lot of readers, and Ansari can see why: “It’s very powerful in first person because it wasn’t about what miscarriage looks like from the outside.”

But some people see these pieces as self-indulgent and an easy out for writers. Janice Tibbetts, a journalism instructor at Carleton University, says she has nothing against first-person narratives and doesn’t call herself a critic of them, but doesn’t see much growth in them for a journalist. “It’s the kind of thing I don’t see as a skill that takes a lot of time to develop.” This is the main reason she doesn’t allow her first-year students to use the first person. Writing about yourself can simply be “the path of least resistance.”

In an article attacking first-person journalism in September, Laura Bennett, a senior editor at Slate, argued that websites such as xoJane, Buzzfeed Ideas and Gawker are turning any thought or experience a writer has into a meaningless article. But, she noted, personal stories are often the only way for young journalists to get a response from publications. And the ones that gain traction are those that describe something terrible that a writer had to go through.

For freelance journalists, the personal essay is a quick way to make some cash—no research or fact-checking required. Writers who can’t afford to spend much time on each of their stories in order to make enough money to survive know they need to give a good pitch or they won’t be published. The stories that grab attention are ones about sad and painful events. Bennett quoted Jia Tolentino, Jezebel’s features editor, who says, “Writers feel like the best thing they have to offer is the worst thing that ever happened to them.”

Meanwhile, Hamilton Nolan, who wrote “The ‘Writing About Yourself’ Trap” on Gawker, wants journalists to remember that getting published doesn’t have to mean writing “sexy, salacious, crazy, wild, demeaning, shocking, depressing or self-glorifying stories.”

Despite the critics, websites find value in these stories, under the right circumstances. Souzan Michael, associate digital editor of Fashion Magazine’s online site, says she carefully decides when a first-person story will speak to a topic better than it can be told otherwise. She wants stories that are true and relatable, which can only be done “by being yourself.”

After all, first-person narratives use something we do all the time—storytelling about ourselves—to explore difficult and uncomfortable subjects. Good journalism, in other words.

by Blair Mlotek

Blair Mlotek is the Online Handling Editor for the Spring 2016 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.