Drawn In

It's often hard work for little pay, but David Collier combines his love of reporting and drawing in an increasingly popular genre—comics journalism

I recognize David Collier’s face immediately. The self-portrait illustrations in his comic books are remarkably accurate, although the three-dimensional version standing before me is taller and better built than I expected. After shaking hands, we head outside to the rainy streets of Hamilton.

The short walk from the bus terminal to Collier’s home studio unfolds like a comic strip. A stranger snaps our photo in front of the downtown skyline. In Jackson Square, a grey-haired gentleman rails against the arrogance of Torontonians. At the farmers’ market, Collier buys a bunch of carrots the size of cucumbers. He buys me one too. Back outside, Collier points out several new art galleries that have opened this past year. We take a tour of the Print Studio, a new artist workshop in town, and, a couple of buildings down, we watch a video installation of Detroit and Barcelona downtown street intersections at the Hamilton Artists Inc. gallery. With Collier acting as a guide, Hamilton’s streets are a story in the making.

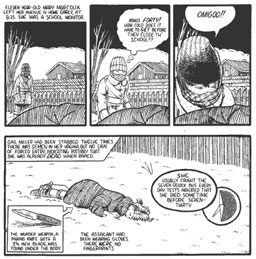

Collier is one of Canada’s best-known comics, or graphic, journalists. His illustrated essays include stories about David Milgaard, Grey Owl and Dr. Humphrey Osmond, the man who gave Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World and The Doors of Perception, his first dose of mescaline. He’s also done considerable illustration and comic strip work for various newspapers and magazines across Canada and the United States. His career emphasizes the acceptance of comics journalism and the growing desire of Canada’s print media to add it to their pages.

Comics journalism, and comics in general, are rooted in the tradition of political cartooning. In the mid-19th century, new publications like Canadian Illustrated News and Grip began using cartoons to satirize Canadian political events such as the Pacific Scandal that embroiled Prime Minister John A. Macdonald in 1872-3. Eventually, single-panel cartoons were expanded and the first comic strip was published in 1895 in the New York World. The first strips moved away from politics and used humour to attract readers. The “funnies” were born. The Depression brought a need for escapism and led to the adventures of Dick Tracy and Tarzan. In 1938, the first issue of Action Comics heralded the arrival of Superman. A flood of superhero comics followed, with two companies – DC, the home of Superman and Batman, and Marvel, the house of Spider-Man and The Fantastic Four – dominating the genre over the next 30 years.

But by the late 1960s, comics had drawn itself into a corner. Well past middle age, the exploits of superheroes and themes of adventure had left its readers stuck in adolescence. An underground movement – which included the early works of Robert Crumb – began producing self-published comics for adults that chronicled the events of everyday life. Stories about work, relationships and family were standard themes of underground cartoons. Subject matter continued to evolve and become more sophisticated to the point where, in 1986, Art Speigelman’s graphic memoir of the Holocaust, Maus, won the Pulitzer Prize. The underground adult comic had finally reached the mainstream.

A decade later, Joe Sacco produced a seminal work, Palestine, about his experience during a two-month visit to the occupied territories in Israel. The deliberate subjectivity, a cornerstone of comics storytelling, gave Sacco’s work an emotive quality that drew readers in and connected them to a story more often told with sterile neutrality.

During this time, Collier established himself as a professional cartoonist. In 1986, he published his first strip in the Crumb-edited Weirdo magazine, but it wasn’t until he left the Canadian military that he began his trade in earnest. Most of his material was published in comic book journals, including the fledgling Drawn & Quarterly, which emerged in 1990. Chris Oliveros, its first and only editor, was committed to long-form comics narratives and gave Collier room to experiment with his unique blend of storytelling.

The reportage method of Sacco and Collier is akin to Tom Wolfe’s New Journalism. They use scenes, details and dialogue to tell their stories, and almost always provide a point of view. Comics journalism rarely enters the realm of daily news. When combined with research and reporting, the labour of drawing and writing a comics narrative doesn’t lend itself to the immediacy of current affairs.

On the heels of Sacco’s success, magazines like The New Yorker, GQ and Details were suddenly covering political conventions, awards shows and criminal trials through illustrated narratives.

In 1995, the Saskatoon Star Phoenix began running one of Collier’s comic strips, titled Saskatoon Sketches, which documented life on the Prairies. It ran for six months until Collier, hoping to syndicate south of the border, suggested changes to the serial. The paper’s editors weren’t enthused, and the comic was dropped.

Despite the odd setback, interest in the form continues to grow. The graphic novel has become hip, and Canadian cartoonists like Seth and Chester Brown have become minor celebrities. Recently, the Art Gallery of Ontario featured a collection called Present Tense: Seth. More than ever, editors and art directors are anxious to get involved.

“I would love to have a whole feature as a comic,” says Antonio Deluca, creative director at The Walrus. One of his biggest challenges is to figure out how to present it without alienating a readership that expects an emphasis on the written word. “A lot of people look at it and don’t get it,” he says. The Walrus‘s section will consist of two pages to start. It’s not enough for a lengthy feature, but in a culture where, increasingly, knowledge is interpreted visually, Deluca believes the genre will eventually get the space to grow.

Serialization is often the solution to running longer comics narratives within the limited confines of magazine and newspaper layouts. But, Toro editor Derek Finkle notes, running a serial can be risky business. “It can make an editor nervous,” he says, “because you don’t know what you’re getting.”

It can be successful though. This past year, the Edmonton Journal serialized illustrated stories about David Eamer, North America’s first paraplegic truck driver, and former Edmonton Oilers hockey star Paul Coffey. Co-writers David Staples and Jill Stanton plan on doing more illustrated stories as newspapers continue to push the boundaries of back-page comic strip tradition.

And, in the Saturday, Oct. 22 edition of the National Post, The Financial Post section leads, on the front page above the fold, with a comics journalism feature called “David Brown: Man of the World.” The story, illustrated by Mike Faille and Kagan McLeod, portrays the excessive use of expense claims by Brown, the former Ontario Securities Commission chair. Brown spent over $600,000 on world travel during his seven-year tenure as provincial securities watchdog.

At the Montreal Mirror, Rupert Bottenberg recently commissioned an illustrated report on the International Comics Festival in Angoul?me, France. A music editor for the alternative weekly as well as a cartoonist, Bottenberg believes the value of comics journalism is found in cultural and entertainment reporting and criticism.

In 2001, Bottenberg interviewed DJ Mr. Scruff in comics format. His character, a cassette tape man, asked Mr. Scruff’s illustrated character a series of questions. Bottenberg was allotted the same amount of space as for a written review, which only highlighted the physical limitations of comics journalism. “It struck me that the amount of text available to me would be minimal,” he says. “The interview would be reduced to about a dozen sentences.” As a result, the interview as presented lacked depth, but many readers nevertheless told Bottenberg that it was one of the funniest interviews they’d read. “Not because it was a particularly good interview, but because it was completely distinctive from anything they had read before.”

Bottenberg says cartoonists tend to lead a hermit-like existence, but the opportunity to report on far-off events doesn’t present itself that often either. Collier recently reenlisted in the army reserves to become a member of the Canadian Forces Artist Program. He was scheduled to go to Afghanistan this past year, but couldn’t get insurance to travel to the country, so the trip was cancelled. Instead, he spent time on the HMCS Toronto and his illustrated diary was published in the CBC.ca Arts section.

Canadian magazines and newspapers are reluctant to commission expensive assignments, and few cartoonists have the loose change to pay their own way. Getting the opportunity is often just a matter of being in the right place at the right time. Pyongyang, Guy Delisle’s journal about North Korea, came about when the animation company he worked for moved its South Korean operations to the capital of North Korea.

Brown, author of a graphic Louis Riel biography, thinks the challenges all but ensure that comics journalism will remain an anomaly. “It’s not going to replace any other form of journalism,” he says. “It’s too much work. I just don’t see many cartoonists doing it for long.”

Collier doesn’t plan on giving up. There were two things he wanted to do while growing up – draw and work for a newspaper – and comics journalism allows him to do both. He remains committed to the duality of illustration and reporting despite the time it takes to construct a story. The expanding interest of Canada’s print media in comics journalism should provide Collier with plenty of opportunity to continue living his childhood dreams.

The rain has stopped by the time we reach Collier’s home. The walls of the studio are covered in posters and newspaper cutouts of illustrations and comic strips. An overflow of paper clippings is fastened by clothes-pegs to clotheslines crisscrossing the room. Skis bundled like kindling are harnessed to the ceiling above the desk. After a few more questions, it’s time to go. We shake hands for the second time today and I walk back into town. Without Collier beside me, the streets are unrecognizable.