Trouble is His Business

He battled Hells Angels. He brought down a dirty cop. He exposed pimps who exploited teens. He’s one of our top investigative journalists. So why does Julian Sher struggle to find work?

It’s 5 p.m. and Washington, D.C. buzzes with pencil-pushers crowding into Beltway bars. Julian Sher joins them at a spot not far from FBI headquarters and the U.S. Department of Justice. One Child at a Time, his book about the child pornography underground, has just come out and he’s here to catch up with two of his sources. Special Agent Emily Vacher is petite and blonde, casually dressed in jeans; Drew Oosterbaan, chief of the Department of Justice’s Child Exploitation and Obscenity Section, towers almost a foot above Sher and looks Viking-like, save for his customary suit and tie. They can’t get a table, so they stand at the bar and talk about the investigative journalist’s next project.

“You should do something about child prostitution,” says Oosterbaan.

“Really?”

“Yeah,” says Vacher. “In terms of child abuse, internet predators are important, but there are hundreds of thousands of other girls who are being ignored.” They tell Sher about their work to save child prostitutes and he’s shocked to hear they’re talking about American kids, not foreign children subjected to trafficking. “It’s the girl next door, the girl from the wrong side of the tracks,” says Oosterbaan. “These are the invisible children.” Vacher nods and says, “The FBI’s got a whole squad of people now doing nothing but trying to rescue these kids and going after the pimps.”

Over a career spanning more than three decades, Sher’s heard from lots of people who want their stories told: the wrongfully convicted, after he helped unearth the truth about the shoddy police work in Steven Truscott’s case; the informers, after he co-wrote two books about the Hells Angels. These are mostly people with personal agendas, but this tip was coming from two insiders he trusts. He also knows Vacher and Oosterbaan can open doors for him in his research.

Sher is good at keeping in touch with his sources. Whenever he finds himself anywhere other than his native Montreal, he tries to give someone a call: the people who fought the KKK in his 1983 book White Hoods; the cops he met a decade ago while writing about the Hells Angels; or the Truscott family, to whom he devoted 10 years of his life. He wants to see how they’re doing and catch up, but he gains more than friendship from keeping contacts close. His stories are often interconnected, with a previous source leading to the next big idea. And Sher knows his connections keep him a step ahead of the pack, because the problems he runs up against are not uniquely his. All investigative journalists face them today: risk-averse book publishers, budget-slashing broadcasters and media-induced shortened attention spans. Investigative journalism doesn’t quite fit in; its need for more words and more airtime makes it a difficult sell.

Fuelled by his tenacity and natural gift as a networker, Sher’s work has appeared everywhere from The Globe and Mail to CBC’s the fifth estate. But media outlets’ commitment to investigative journalism is fading. Investigative stories are costly to produce in any medium, and space and funding are dwindling. With a trail of successes behind him, even Sher can’t see what lies ahead.

Sher can barely sit still. As he talks, his hands are in constant motion, as if they are what push his ideas forward. He talks fast; perhaps his second career choice could have had him standing at the auction block. But the 56-year-old never had any interest in auctioneering. He always wanted to be a journalist. After writing a serial thriller for his summer camp’s newspaper, contributing to a newspaper for children in the hospital when he was a grade schooler and writing an annual play for the kids near his family’s summer cottage in the Laurentians, his career seemed set. And from the beginning, he was ambitious: At his high school paper, his first interview—with questions and answers sent by mail—was with Pierre Trudeau. He chose McGill University largely because he wanted to work at TheMcGill Daily, where he was a fixture for five years while getting a history degree. There, he became involved in student politics, including backing a support workers’ strike—a galvanizing moment. He spent the rest of his 20s involved in campus activism and writing for the left-wing Montreal newspaper The Forge. He worked at United Press International and at the Westmount Examiner before he accepted a one-day contract at CBC Radio’s Daybreak in 1983. He ended up staying there until nabbing a position in local TV. In the late 1980s, Sher helped produce an investigative segment about poor roadway infrastructure for CBC Montreal’s supper-hour show, Newswatch. It caught the attention of Kelly Crichton, a producer at the fifth. “It showed he knew how to dig,” she says, “and he wasn’t afraid of flak.” She asked him to fly to Toronto to talk about working for the current affairs program. He found himself on the same plane as his first interview subject. Sher struck up a conversation and, later, when Crichton asked about his flight, he told her about his encounter with the former prime minister. He got the job.

* * *

After their chat in the bar, Oosterbaan puts Sher in contact with prosecutors who try cases involving child prostitution. He starts talking to them. He wants to understand the law. Federal prosecutor Sherri Stephan tells him about a pimp she tried for conspiracies to commit trafficking and money laundering. Sher is shocked that she and Assistant U.S. Attorney Jason Richardson were able to put Matthew “Knowledge” Thompkins away for nearly 25 years. Sher keeps digging. After Vacher tells him about the FBI’s Innocence Lost National Initiative, he writes to the bureau, telling the agents about his book involving the Innocent Images unit, and asks them for access. That gets him an interview with the taskforce heads, and leads to a list of the unit’s best agents across the country. Sher contacts Dan Garrabrant, a New Jersey agent who tells Sher about his cases and mentions a girl from Atlantic City referred to as Maria. Garrabrant’s been trying to help her since they met during an arrest when she was 17 years old—four years into her life as a prostitute. But her name is one of many, and Sher doesn’t get the details of her story for two months. When he does, Garrabrant provides a thorough explanation of her case, including the name of her former pimp: Knowledge.

* * *

I’m not in the good news business,” Sher says. Instead, he likes stories that “hold a dark mirror to society.” He wants to make people uncomfortable. But he did more than that with one 1992 piece he produced for the fifth. Sher and the rest of his team, including reporter Hana Gartner, were looking into gangsters running drugs in Montreal when associate producer Dan Burke talked to RCMP drug inspector Claude Savoie. They had no idea Internal Affairs was already investigating him for accepting bribes, but with each question they asked, more questions cropped up. They were suspicious of his associations with drug kingpin Allan Ross and added the information to their story. Twenty-four hours before the documentary was set to air, Sher and his team learned that Savoie had shot himself in the head with his service revolver while two officers inRCMP headquarters were preparing to question him. “We were both like whirling dervishes,” remembers Gartner. “No story is worth anybody offing himself.” They hurried to the studio to film a stand-up so she could add the news to the story, as well as to include recorded conversations between Burke and Savoie. It aired on schedule.

Investigative journalism can drastically alter lives—even play a hand in ending them. It’s part of the job, and Sher accepts that. But only because he has to. Savoie’s suicide still weighs on his mind. His eyes drop and his near-constant smile fades as he says, “All I could think was that his kids would never have another Christmas with their father.” He looks down at his unusually still hands, then looks up again. “But I have to remind myself that I’m not the one who accepted the bribes.”

Other times, investigative journalism drastically alters lives for the better. Steven Truscott, wrongfully convicted of murdering Lynne Harper in 1959 when he was 14 years old, had lived under an assumed name since his release from prison in 1969. Early on in Sher’s investigation, he and reporter Linden MacIntyre spoke with Truscott. While MacIntyre was more sympathetic, Sher told him, “If you want somebody to clear your name, hire a defence attorney. That’s not our job. But if you give us free rein to investigate wherever we can, that’s what we’ll do.”

His approach to the story was simple: presume Truscott’s guilt, but examine every piece of evidence to see if all the pieces of the puzzle fit. Sher and his team read all the reports, scoured every court transcript, and talked to any witnesses still alive from that time, as well as witnesses who never took the stand. The team resubmitted the original medical evidence to modern-day experts, the results of which showed that “the initialmedical examination was a sham,” says Sher. His crew found one crucial fact: a dubious time of death in the autopsy report, which MacIntyre calls “scientifically impossible,” helped prove Truscott could not have been the killer. Without Sher’s research for the documentary and for the book he later wrote—“Until You Are Dead”: Steven Truscott’s Long Ride into History—the Ontario Court of Appeal might never have acquitted Truscott.

* * *

The pimp known as Knowledge helped bring Sher’s latest book together. He was the connection between theFBI’s story and the prosecutor’s case. Although he never answered the letters Sher sent him in jail, his story still gives the book—tentatively called Somebody’s Daughter—a narrative thread. But girls like Maria, the former child prostitute, give readers a reason to care about the book. If only someone would publish it.

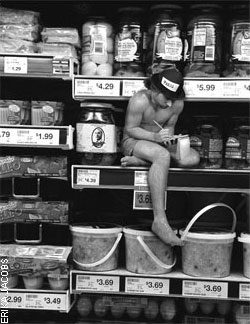

“Prostitutes are only seen as ‘black hos’ or ‘white trash,’” says Sher. “The whole point of the book is that these girls are neglected and nobody cares about them. So it’s a little hard to convince a publisher to do a book about kids that nobody cares about.” Diane Martin, publisher-at-large of Random House Canada, attests to this. She worked with Sher on some of his previous projects, but says, “I’m not sure what would motivate people to spend say, $32, for a hardcover on that subject. I know I wouldn’t.” Book sales in Canada are holding steady, but this story is too gritty for most major publishers and retailers. “Places like Wal-Mart and Costco are big customers now. If they think their buyers won’t be interested, they won’t buy it.” And this book might be too much for those shoppers.

Sher pitched his idea to Random House, HarperCollins and Disney’s Hyperion. All liked it, but knew they’d never get the book by their sales departments. All declined.

* * *

We’re on our way to meet editor Ilona Crabbe in a CBC edit suite in Toronto. Sher is working with her on an episode of a six-hour series about World War II called Love, Hate and Propaganda. After we get there, they start talking about the firebombing in Tokyo and whether or not to use some costly stills of bodies charred in American attacks.

She leans back in her chair, rocking, hands behind her head and legs crossed. He sits at a long table behind her, leaning forward to read the script in front of him. They talk over each other, Sher’s hands flailing. His colleagues at the fifth nicknamed him “the hamster” for a reason. He taps his pen on the script while Crabbe continues rocking in her chair. He highlights what he needs to fix, then they talk about the pictures again—one of a charred baby in particular.

“I’m going to fight for that picture,” says Sher. “We’re trying to show the horrors of war here.”

We watch the scene on the monitor to our left. Crabbe stops the video. “Is it too gruesome?” Sher asks me. I say no, it wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be.

While Crabbe sets up the mic for his voice-over, she sings the Mickey Mouse Club theme song under her breath. After recording, they dicker over the script and try to find another word for “featured.” Before we leave, they watch a scene about American propaganda and Sher and Crabbe dance ironically, bodies twisting and fingers pointing in the air, while on screen the musicians sing, “We’re gonna have to slap / the dirty little Jap.”

The World War II documentary isn’t Sher’s usual story. He isn’t burrowing into a tight-knit community to save the underdog. He doesn’t have to worry about anyone shooting at him or suing him. A piece like this gets an average budget of $500,000, and with this six-part series, CBC hopes to reach a younger audience—even hiring George Stroumboulopoulos to host. Sher likes the idea of doing something out of the ordinary. He’s seen a lot of changes in investigative journalism during his career and believes the current scarcity is a reflection of the shift in what media head honchos are willing to pay. “I think there’s a lot of penny-pinching by short-minded publishers, or even managers in broadcast. It’s funny; they’re interested in cheap reality shows,” Sher says. “Duh, what greater reality show is there than investigative journalism?”

* * *

Somebody’s Daughter is almost complete and Sher still hasn’t signed with a publisher, so he tells his agent to devote his time to more lucrative projects. Then Sher tries something he’s never done before: after five books—four with major publishers—he sends his unsolicited manuscript to 12 independents. He doesn’t hear back from most of them. He gets feelers from a couple. And then, he gets a call from Chicago Review Press, which wants to publish the book that seemed so undesirable. Sher will get $10,000 upfront, but it’s a smaller advance than he’s used to.

Catering to fewer and fewer outlets is the reality for today’s independent investigative journalists. Sher juggles many projects to keep busy and to fund the ones he struggles to sell. “Books and freelance are in many ways the way to go to do investigative work. But you can’t survive on that,” he says. “So you have to do whatever documentaries and other freelance stuff you can to pay for spending two years on writing a book about child prostitution.” He flew to the U.S. with reward points he’d saved; when his destination was close enough to home—New York City, for example—he took the train. Sher believes there’s still a thirst for important, well-researched stories, but even good journalists have to be lucky to get a stint at the fifth or sign a contract with CBC’s documentary unit. “We don’t have that feeder system—that training system—that’s grooming the next generation.”

Sher aimed to foster future talent himself by starting JournalismNet, a collection of online tools for reporters. He’s since sold the site to a U.S. internet company, but continues doing newsroom training on web research techniques. He’s happy to spill the secrets of his working process to anyone who will listen. If a story needs to be told, he says, it doesn’t matter who tells it. He’s trained reporters at BBC, CNN, CBC and CTV, and they all have good things to say about him. So do his colleagues—more than one of them apologizes for telling me how much they like him because they’re sure I’ve heard it all before. Only Ricky Ciarnelleo, a spokesman for a B.C. branch of the Hells Angels, is less than complimentary—and even then, his opinion seems tepid for a member of a biker gang: He calls Sher a “pimp” who “sells books instead of women.” Sher’s innate talent for networking, working sources and staying in touch even when he doesn’t need a favour, turns out to be a skill that wins friends, not just scoops. What it doesn’t win is big paycheques.

* * *

Maria, the young girl exploited by Knowledge and saved by Garrabrant, is now 22. Garrabrant holds her newborn in his arms as he, Maria and Sher stand in her parents’ comfortable Atlantic City home. Sher looks on as Garrabrant and Maria discuss baby formula. It seems normal, save for the fact Sher knows their past.

Earlier this year, he completed the World War II doc and had nothing planned for the immediate future. He was “gainfully unemployed” and waiting for Somebody’s Daughter to come out in the fall. But, he recently signed a one-year deal with Global Television to do a series on crime and justice. He also has a pitch out for a book he’s writing about a former FBI profiler who sometimes writes for the TV series Criminal Minds. (He contacted Sher after reading One Child at a Time.)

His connections aren’t just with cops and prosecutors, though. Maria has been out of “the game,” as she calls it, for a while now and wants to go back to school, but she’s had to start stripping to take care of her baby. She tried working as a telemarketer, but couldn’t stand lying to people. Garrabrant, who insists she hasn’t gone back to prostitution, continues to check in on her. So does Sher, even bringing her baby clothes. He understands she’s doing what she must to survive. He does the same.