A lunch in two languages

Last week, The Globe and Mail published a story in English and Chinese—an attempt to start bridging cultures and readers

In last week’s installment of Report on Business’s weekly profile series, The Lunch, one line brings a whole new side to the story. Appearing right before the opening scene, translated to English: “Click here to read the full article in Chinese.”

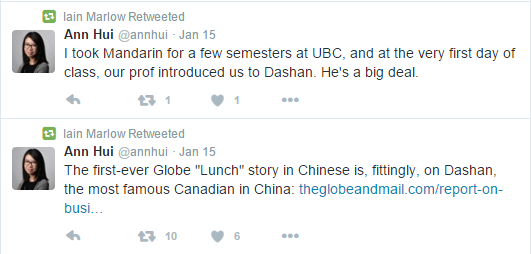

The piece, written by The Globe and Mail’s Asia-Pacific correspondent Iain Marlow, profiles Mark Rowswell, a Canadian famous in China for his comedic performance career. For over 20 years, the Chinese have watched Rowswell on TV under the name Dashan, which means “Big Mountain.” Marlow also writes about Rowswell’s most recent career move in the economic superpower: stand-up comedy. The Globe published the story in both English and simplified Chinese online.

“I was interested in getting the piece in front of people who might not be a natural Globe audience,” Marlow says, “either because they were in China and never heard of the Globe, or because they were people in Canada who would feel more comfortable reading the piece in Chinese.” Unlike his stories about real estate in Shanghai or emerging market economics—which would also be covered in Chinese language papers—Marlow figured the Dashan story would be of interest to a wider audience. To some, it would be a first introduction to a fellow Canadian of foreign fame. To those who’ve watched Dashan for years, the story is a chance to learn more about the performer’s past. Marlow himself heard about Dashan on and off over last 10 years during his travels to China, but only found out in the interview for this piece that he was a student at Beijing University at the time of Tiananmen.

When Marlow brought up the idea of translating the story to his editors, they treated it as an experiment: let’s try it, see what happens and see where it might lead. Marlow asked a former colleague in Beijing to translate it. While the English version explains certain terms to the readers, like the meaning of the name Dashan or what “cross-talk” is, the Chinese version doesn’t have to—a simple, but significant show of mindfulness.

For some, like the parents of one of Marlow’s friends from Shanghai now living in Toronto, it may have been the first Globe article they’ve ever read. The piece briefly linked their Chinese and Canadian experiences. “Even just hearing that was really encouraging and really warming,” says Marlow, who emailed them the article. “The guy himself is a bridge between two different cultures, and I think that was what we were trying to do with the piece in general.” He also finds it signals to a whole group of readers that the Globe is interested in them and their stories.

The Globe has done translated stories in the past. Last July, Stephanie Nolen’s multimedia project on racism in Brazil was also released in Portuguese online. While Marlow is cautious to predict the future implications of his bilingual experiment, it has already yielded an informative, unexpected result for him: no one term for stand-up exists in Chinese. The article and its accompanying tweets weren’t translated by the same people, and each used a different term for the comedic style. For now, it’s another link between cultures still ironing itself out.