A Stoppage in Play-by-Play

Hockey journalists scramble to cover a non-existent season

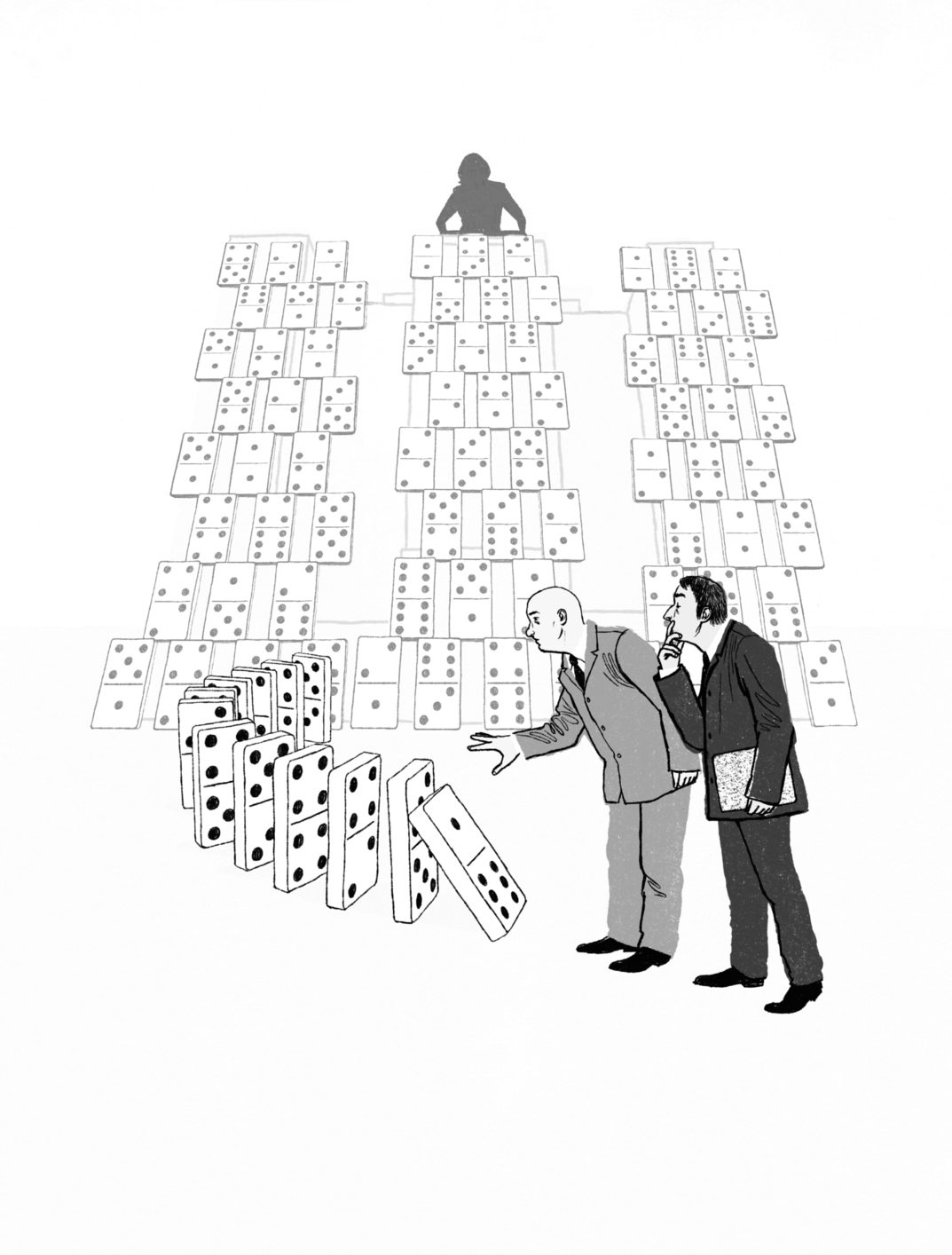

For the past few months, Lance Hornby, Toronto Sun sports reporter, sat at home every evening and rolled dice. Recording the results, he marked them next to a fake National Hockey League (NHL) schedule. Five minutes later, he had the day’s standings, and player statistics, which took half a page in the next day’s edition. The National Post did its own version of a dice league, and CTV announced in October that it would be airing virtual matches (in video game format), instead of actual games.

With no real games or stats and players running off to Europe, sports reporters have had to spend the entire season finding ways to fill up column inches. While the Canadian Football League and, especially, National Football League (NFL) monopolized coverage in most papers, and on most stations, when their seasons ended, the lack of hockey reporting in a hockey nation became even more apparent. Other than the National Basketball Association season to follow, every sand trap and water hazard Mike Weir finds starts to look like a pretty good story.

Too much coverage of the players being locked out by the owners became tiresome. There was little of no news to report. George Johnson, a veteran columnist and hockey writer for The Calgary Herald, says all reportage during the lockout was the same.

“We’ve pretty well determined which writers are pro-player and which are pro-owner,” he says.

While Johnson doesn’t think there’s been an outright polarization among reporters, he says he’s “a bit irked at some of the pro-player advocates, who see the issue only one way.” He attributes this partly to reporters having loyalty to the guys they deal with on a day-to-day basis – guys who provide them with gossip and information.

Pat Grier, sports editor of the Sun, says it will be interesting to see what happens next season. “Players and coaches are taking names. People know who’s on whose side,” he says.

Damien Cox, sports columnist and a 20-veteran of The Toronto Star, says that “there’s been some very public shots taken simply because one person takes a stance on this dispute different than another. It’s all quite unprofessional, but human.” Personally, Cox tries to stay down the middle and think of new ways of presenting hockey when writing his column – but he hasn’t written about the sport besides labour issues and the World Junior Hockey Championships.

“Hockey fans in general are utterly bored with the issues surrounding NHL collective bargaining,” Cox says. “It’s different from the last lockout. Back then, there was a constant drumbeat of a possible resolution, the solution was more fluid and there were more people offering daily comment, which made for a livelier story.”

Other reporters escaped the lockout coverage by following players that went to Europe. But as Post sports writer Jeremy Sandler points out, time and language constraints don’t always make that a viable option. “You have to stress yourself,” he says. “The lockout slowed things down and you might not have had a story the next day. You have to think more laterally.”

Steve Argintaru, senior assignment editor at TSN, agrees. In order to fill the same 90-minute commentator time slots that normally air during a regular season, the network has been digging for entertaining stories, instead of the usual highlights banter. Argintaru doesn’t consider this a bad thing. “It keeps us sharp creatively,” he says. “It allows us to get out to other parts of Canada that we probably wouldn’t be reaching.”

Argintaru cites sending a reporter to Florida to cover former NHL goal-scoring great Pat LaFontaine running his first marathon. “If there was no lockout,” he says, “we wouldn’t have sent a reporter.”

“Most sports journalists have done other types of reporting,” Sandler says. “Those that thought they weren’t being challenged went to the general assignment desk – but there weren’t many.”

Some outlets, such as The Hockey News and CBC’s Hockey Night in Canada, have suffered. Halfway through what would have been a normal season, the Hockey News, with a circulation of roughly 100,000, announced that it would be cutting its output by half and running biweekly, rather than weekly.

“It was a decision made for lots of reasons,” says editor Jason Kay. “We talked to our readers and although they thought we were doing a good job under the circumstances, we thought we would better serve them by going biweekly.”

Although publicists were unavailable for comment, the rumour was the CBC laid off at least 50 people when it replaced Saturday night hockey with Hollywood movies. But CBC Sports Online producer Andrew Lundy says his writers have been busy, and that his No. 1 story has been the labour dispute. Pre-lockout, he says the CBC signed an agreement to be the exclusive broadcaster of Canadian curling, and no one has been laid off. He won’t speculate how many jobs the extra curling coverage would have created.

The lockout has opened doors for more coverage on amateur sports, female sports, and lacrosse, Canada’s other national sport. But “just because it’s there,” says Argintaru, “doesn’t mean it interests people.” TSN covers the four major sports: baseball, hockey, football, and basketball. Argintaru figures that if something doesn’t interest viewers while hockey is on, it won’t interest them while the players are locked out.

“You can’t tell readers what they’re interested in. But that’s what makes people better at finding other stories. You’re used to having it handed to you,” Sandler says.

Finding alternative stories doesn’t necessarily mean replacing hockey with popular sports. Although there has generally been more room for longer football and basketball coverage in print and on air, the lockout hasn’t allowed for any more allocated time or space. Both NBA writer Frank Zicarelli and Sun amateur sports writer Mark Keist say the lockout has had little to no impact on the amount of copy they produce.

Junior hockey was an early favourite to replace NHL coverage, but it hasn’t worked out that way. Terry Koshan from the Sun spent a weekend on the Brampton Battalion’s bus, for instance, but in general there was only a slight up-tick in interest from reporters.

Parker Neil, media and public relations director for the St. Mike’s Majors, says they haven’t received more media attention than normal. “I’d like to think we’re high profile enough to fill some of that void,” he says. “But just because there’s a void doesn’t mean they have to fill it with us.” He would, however, prefer to see some of the major outlets use their space to cover “real hockey that’s being played rather than [dice league] hockey.”

Cox says the dice-hockey tactics “are a waste of time and don’t interest any significant chunk of fans,” but Sandler disagrees. “This is hockey,” he says. “It’s supposed to be fun.”

Whether or not the lockout will have a lasting effect on sports journalism in Canada is up for debate. According to Sandler, nothing significant will change. “When hockey swings back into full gear it will be covered as much as possible,” he predicts.

Cox agrees with Sandler, with a proviso: “It could be that, in the future, Canadian media outlets will be less inclined to commit permanent resources to covering the NHL.”

The dice leagues eventually lost steam. On January 23, the Sun dropped the rest of the season and shifted to playoffs. Grier felt that continuing the entire dice season as a normal NHL season would be too much, and gave the readers what they wanted: playoffs.

“Part of it was meant to mock what the NHL was doing,” Grier says. “The whole venture ran a bit stale.”