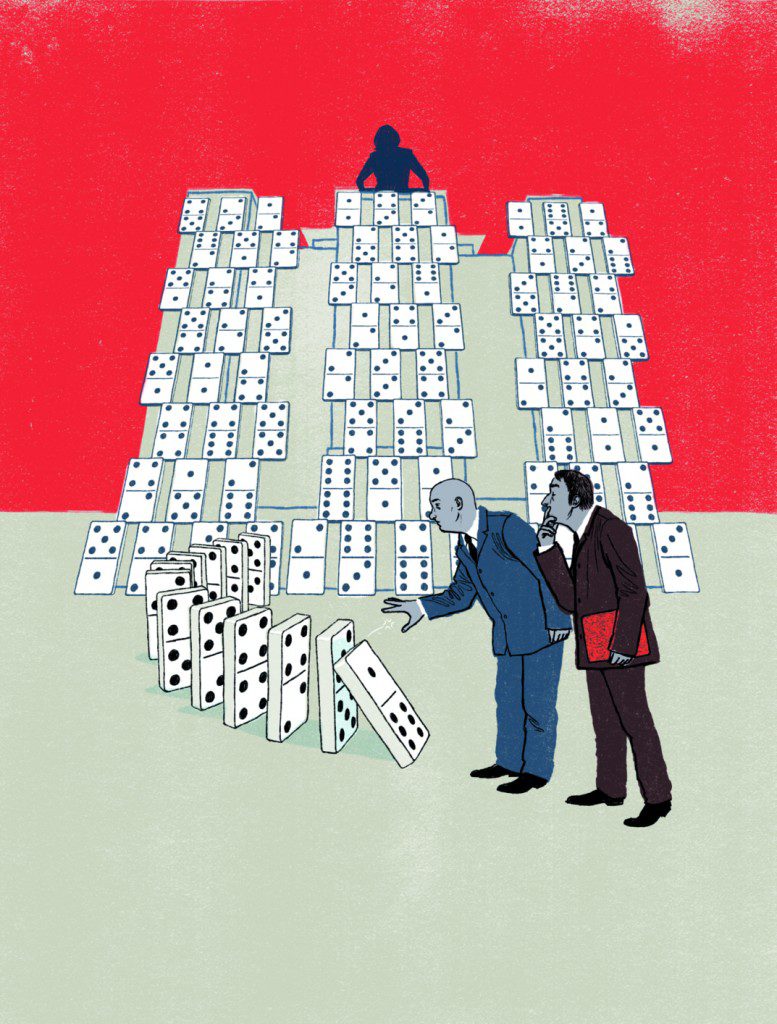

The Harder They Fall

When Alberta reporters revealed a series of Alison Redford’s scandals, it created a domino effect and sent her tumbling out of office

Hundreds upon hundreds of documents: that’s part of the evidence Charles Rusnell and Jennie Russell needed to break one of their biggest stories about Alison Redford, the Alberta premier who was, at that point, already besmirched. It was March 27, 2014, and both CBC Edmonton reporters were sitting on a major scoop that would further disgrace her.

For months, rumours had been circulating that Redford planned to construct a penthouse suite on the 11th floor of Edmonton’s Federal Building. Despite its name, the 1950s art deco property is provincially owned, and it was under renovation to create office space for Members of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta (MLAs) and their staff. But no one could confirm the construction on the top floor was for the premier’s personal use—until now.

Over the span of about two months, Rusnell, a veteran journalist leading the investigative unit, and his colleague Russell filed six freedom of information requests with different government departments. They wanted proof of Redford’s misuse of taxpayers’ money. “We sought a government source who had direct knowledge of the building,” says Rusnell. “We knew that other media outlets and one opposition party had tried and failed to get the floor plan.” A source suggested they put in a request for communications between the premier’s executive assistant, Ryan Barberio and the architect in charge of that floor. Then the documents came in: 800 pages detailing Redford’s plans for “sleeping and grooming quarters with clothing storage” for an adult and a teenager.

The CBC reporters had an exclusive story but they needed to act fast. In a boardroom on the south side of the newsroom, Rusnell and Russell huddled with senior television producer Neill Fitzpatrick, assignment editor Kelly Banks and senior radio producer Ann Sullivan. They packaged the piece in less than 12 hours, before the government made the documents public at 1 p.m. the next day—a tactic Alberta officials often use in an attempt to shorten the news cycle of a scandal. At 5:30 a.m., the story

journalists dubbed Skypalace broke first on the radio, then online and, finally, on television.

Though the story didn’t kill Redford’s career—she had announced her resignation as premier nine days earlier—it was another major blow to her credibility, and a triumph for reporters rooting out government corruption.

Carleton University political science professor Scott Bennett says provincial politics remains “an incredible area of public ignorance.” That ignorance can often be a struggle for reporters. “What’s depressing as a journalist is that you just become conscious of the fact that the public actually doesn’t give a shit about ethical or moral corruption,” says National Post reporter Jen Gerson, who also broke her own story about Redford’s spending.

Under the uninterrupted 45-year reign of the Progressive Conservative Party, Alberta has become the province with the longest-running single-party government in Canadian history. Investigating politics here can be particularly challenging. Reporters struggle to gain access to government documents and must rely on inventive research methods to get information in the public interest. Even when they succeed, their work doesn’t generate the attention it deserves. But last spring, as the Wildrose Party became Alberta’s first viable opposition in years, coverage of Redford captured the public’s imagination. Reporters on the story fought to improve government transparency, and by engaging a public often indifferent to scandal, they precipitated a political implosion the likes of which the province had rarely seen before.

***

Redford became the subject of scrutiny shortly after she became premier in October 2011. Her initial response was a “textbook case of how not to manage controversy,” Post contributor Dan Arnold wrote. An early investigation revealed 21 MLAs were paid $1,000 a month to sit on a committee that had not met in over three years—a committee on which Redford herself once sat. It was, as Arnold describes it, “money for nothing.”

Then, in January 2014, Gerson filed a story about the lavish expenses Redford racked up on a trip home from South Africa, where she had been attending Nelson Mandela’s funeral. It took eight days of pestering the premier’s press secretary over email—“I need the number, I need the number”—but Gerson finally confirmed the figure: that flight home cost the province $10,000. “I actually sat on that for a couple of days,” Gerson recalls. Given the magnitude of other stories that emerged from Redford’s office, this one seemed fairly tame—but it was the first to capture national attention.

In the aftermath of the Mandela flight scandal, journalists kept a close eye on Redford. Rusnell and Russell knew there was more to the South Africa story, but they were also in the process of obtaining the email exchanges detailing Redford’s penthouse construction at the Federal Building.

They pursued the Skypalace story because they thought it was in the public interest. It wasn’t until the documents came in that they knew it was a sensational story that would outrage the public. Shortly after CBC published their investigation, other news outlets followed. Russell says the stories “got a lot of traction because they all went national—not just because of our reporting, but because every media outlet in the country essentially followed.”

Reaching an Albertan audience can be difficult because of the province’s complacent political environment and its place in the country. Russell refers to the phenomenon as regionalism: because the province is west of the country’s political centre in Ontario, stories tend not to go national. Journalists say government interference is also often a problem. Filing freedom of information requests with the PCs about internal government issues, for one, is tricky because the party has been in power for so long. The process, Rusnell says, is “politicized” because “they can decide which documents to put up.” On occasion, he and Russell file freedom of information requests on their freedom of information requests. They hope to catch patterns of political interference and understand how their requests are being managed—or mismanaged. They find the government sometimes withholds information, which allows politicians the time to come up with talking points to spin the story.

The pair claims to be the only full-time investigative team in Alberta, but for television viewers this appears not to be a priority. In Edmonton and Calgary, CBC News still ranks third in TV ratings behind Global and CTV. Reporters are generally expected to find time to file freedom of information requests alongside their other duties. Most find it is easier to piggyback off the work of others—hence the widespread replication of Rusnell and Russell’s work. Though this didn’t necessarily advance the story, it did give it a national profile.

***

With a government as uncooperative as Alberta’s, reporters have to get creative. Rusnell and Russell were still looking into Redford’s travel expenses in late March 2014. Although Redford had stepped down from the premiership, she kept her seat in the legislature. Russell decided to sift through the province’s public flight manifests and came across more damning evidence: Redford’s daughter had flown on 50 separate government flights. The reason for the trips was described in the manifests as “meetings with government officials,” but the reporters couldn’t find evidence that such meetings occurred. They reached out to Craig Loewen, communications director for interim PC Premier Dave Hancock, seeking an explanation for Redford’s travel, but Loewen declined to comment.

Russell also noticed an unfamiliar name on the flight register: Angelita Escultero. She searched the name on Facebook and found photos of a woman with Redford’s daughter. Escultero was also a member of a Facebook group for McDonald’s employees. In April, the reporter tracked down the fast food restaurant’s location in Calgary and took a bus from Edmonton to confront her. Escultero confirmed their suspicions: as a nanny, she had travelled with Redford’s daughter on one of those government flights. This exclusive story triggered an RCMP investigation into Redford. Rusnell gives full credit to Russell’s sleuthing, noting that in Alberta, journalists need to find resourceful ways to work around the system. “You either have it or you don’t,” he says. “It is difficult to train someone to think in an enterprising way.”

By mid-summer, as journalists and the public anticipated Auditor General Merwan Saher’s report on Redford’s flight expenses, Rusnell and Russell received part of a draft copy of the report. It was leaked by a confidential source who feared that a watered-down version would be released under pressure from the government. The document was of substantial public interest; not only did it confirm CBC’s previous reports about Redford using government planes for personal benefit, it also highlighted the practice of booking false passengers on flights so that Redford and her entourage could travel alone.

To ensure the tip wasn’t politically motivated, Rusnell and Russell later met with the source at a Tim Hortons in Edmonton one Saturday in late July. “There was also a time crunch because we published the story on July 29 and we knew the auditor general was set to release his report sometime early the next month,” says Russell. “We knew we had to get it up early in order to not be preempted by the actual release of the report.” Eight days later, Redford finally announced her resignation as MLA for Calgary-Elbow, marking an official end to her time in office.

***

Despite the successful investigations into Redford’s abuse of government spending and excessive entitlement, some critics believe journalists were too hard on the former premier. Throughout her time as leader—and during her downfall—Redford was often referred to as “elitist” or “standoffish.” According to Gerson, she became known as an “unquotable” speaker with a vendetta against reporters. “If she didn’t like you,” says Gerson, “you weren’t getting an interview.”

Former PC campaign manager Susan Elliott, a blogger for the Calgary Herald, says the coverage was unfair. “I do believe there’s a gender factor here,” Elliott says of Redford’s oft-noted irritability. “It’s not unusual for politicians, who live in the kind of pressure-cooker world in which they live, to have a temper. But because she was a woman, that suddenly became unforgivable.”

Russell denies that, claiming critics are often misinformed about how journalists reported on these issues. Some detractors suggested they wouldn’t have reported on the “daughter flights” story had Redford not been a woman, but Russell says, “I think it’s sexist not to pursue this story.”

Rusnell also insists the investigations into Redford weren’t personal—the journalists were just doing their job. That means divorcing themselves from the outcome of their work, says Gerson, and focusing on what’s in the public’s interest. “If you’re doing this job with an outcome in mind, you’re an activist,” she says. “If I wanted the PCs to go down, I’d go work for the opposition.”

The auditor general’s findings validated the investigative reporting and confirmed that Redford was personally benefitting from government-funded flights. But journalists can’t always count on such reports to verify their work. That’s where David Studer, CBC’s director of journalistic standards and practices, came in. He worked alongside Rusnell and Russell as they rolled out scoop after scoop, always with due diligence. Journalists need to be aware that they are dealing with a high-profile person, he says. “You never want to get it wrong, but you particularly want to be careful about damaging someone’s reputation who has worked so hard to get here.”

***

In early February 2015, journalists visited the newly renovated Federal Building. The original budget was $356 million but the project cost $53 million more than that and took an additional two years to complete. The 11th floor had been converted into meeting rooms, but as Rusnell walked through the space, he saw traces of the previous penthouse layout. He was in awe: the remodelling would have been more luxurious than what was previously documented.

Even in the wake of the Skypalace scandal, not much is new politically. Last fall, Jim Prentice became the new premier and leader of the PCs. Since being in power, he’s revived the Conservative brand. “As everything changes, everything stays the same,” says Tom Vernon, provincial affairs journalist at Global Edmonton. “The PCs get rid of a leader who isn’t doing it for them and replace her with another one.”

Still, the cycles of political scandal make for good journalism, especially for Rusnell and Russell, who pride themselves on conducting investigative work in the public interest. Government sources keep sending them tips, and so they trudge on, seeking to uncover wrongdoings—no matter who’s listening.

Illustration by Martin Tognola

by Stephanie Girardi & Arielle Piat Sauvé

This is a joint byline for the Ryerson Review of Journalism. All content is produced by students in their final year of the graduate or undergraduate program at the Ryerson School of Journalism.