Bright Side of the Dark Side

Though scorned by traditionalists, political life may well be salvation for many restless journalists. Former anchor Ben Chin and others make the case

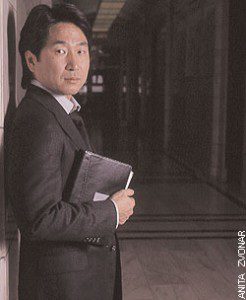

Ben Chin hasn’t been near a television studio in months, but the former news anchor still dresses for the lights and cameras. His tailored suit, cuffed shirt and blue-and-yellow striped tie come straight from a men’s fashion magazine. His new office is another story. Papers and files lie in heaps on top of the wooden desk. Three chairs, one for Chin, two for guests, and a credenza complete the utilitarian look. The only personal touch is a collection of black and white photos – white-matted and black-framed – that includes a shot of his father shaking hands with former prime minister Pierre Trudeau. But Chin has more on his mind these days than decorating his office. After sixteen years in journalism, he’s realized “a life-long dream” by going into politics as a senior media advisor for the premier of Ontario, Dalton McGuinty.

Ben Chin hasn’t been near a television studio in months, but the former news anchor still dresses for the lights and cameras. His tailored suit, cuffed shirt and blue-and-yellow striped tie come straight from a men’s fashion magazine. His new office is another story. Papers and files lie in heaps on top of the wooden desk. Three chairs, one for Chin, two for guests, and a credenza complete the utilitarian look. The only personal touch is a collection of black and white photos – white-matted and black-framed – that includes a shot of his father shaking hands with former prime minister Pierre Trudeau. But Chin has more on his mind these days than decorating his office. After sixteen years in journalism, he’s realized “a life-long dream” by going into politics as a senior media advisor for the premier of Ontario, Dalton McGuinty.

“I don’t think there’s a higher calling,” Chin says, getting comfortable in his chair. The son of a South Korean diplomat, Chin grew up in Ottawa and Toronto surrounded by civil servants. He became a journalist, in part, expecting to cover politics. “That’s the stuff I was really juiced about.” His career provided ample opportunity to report on government at all levels. He worked his way from his first job as a reporter with Citytv in Toronto to CTV as an Atlantic correspondent, followed by anchor positions at CBC, where he occasionally filled in for Peter Mansbridge on the flagship newscast, The National. But as he climbed through the ranks, Chin says, stories started to look the same, and eventually he began to feel like he’d done everything he could do as a broadcast journalist.

In 2003, motivated by the desire to do something different, Chin left CBC and signed on as news director and anchor at Toronto1, the first non-specialty channel in the city since 1974. The station, however, was not successful, passing through three owners in two years. By 2005, Chin had seen enough. He left and signed a contract with Global National to become a Toronto correspondent. He was back where he started – working as a reporter on the city beat.

Before he started his new job at Global, however, an Ontario Liberal insider whom Chin met with regularly as a reporter asked him if he’d be interested in coming to work for Premier McGuinty at Queen’s Park. For Chin, the decision was as black and white as the pictures on his wall. “They said, ‘Would you think about it?'” Chin recalls. “I thought, ‘I would think about it for about three seconds.'” And just like that, Chin was on his way to the “dark side.”

Describing the career move from journalism to backroom or electoral politics (Chin just ran in a provincial by-election in March) as joining the dark side may be cynical, but the leap is a controversial one for reporters and editors to make. For many, it calls into question their independence and non-partisanship, which are core values of the profession. Journalists, at least in ideal terms, are supposed to serve the public good by delivering unbiased reports on the issues of the day. They give up that independence and freedom from bias when they become political insiders. Their work becomes tied to political agendas and the interests of individual politicians, making it almost impossible for them to present themselves to the public again as independent, disinterested observers. As a result, they risk exposing themselves to criticism from former colleagues. More importantly, their move becomes one from which it is difficult to return.

Even so, journalists continue to leave their newsrooms for careers in politics. The October 25, 2005 posting on The Toronto Star blog, Political Notebook, lists six former broadcast journalists, including Chin, who have gone to work for McGuinty. It claims that the premier has been “collecting broadcasters like a network executive.” Most of the reporters are veterans with years of experience and solid credentials, so it might seem odd that they left journalism behind. But Susan Delacourt, a Star political writer, says the business is “notoriously bad in creating fulfilling work environments for people in more senior ranks. Unless you want to be in management or are one of the rarefied few to have a column,” she continues, “then political journalism in your forties and fifties requires pretty much the same skills as in your twenties and thirties.”

At 42 years old, Chin certainly fits Delacourt’s description and when opportunity came knocking, he wasn’t going to pass it up. Luckily, the departure from journalism has been relatively smooth. Chin says he hasn’t experienced open animosity from his former colleagues. Still, he’s careful not to evangelize for his political masters. “That will be a really quick way to lose all my friends.” Chin stays low-key about his political affiliations, but he has no doubts about his career change. “When I said I had to think about it for three seconds, what I had to think about was would I ever want to go back. The answer was no.”

For some, the relationship between journalists and politicians is analogous to that of Sam and Ralph, the Looney Tunes duo. Sam, the portly sheepdog with a mop of red hair covering his eyes, protects his sheep from the industrious but always unsuccessful coyote named Ralph. In each episode the two chat amiably before and after work and during lunch. But once they punch in, the two become the bitterest of rivals and it becomes clear that their professional agendas are at odds.

Similarly, journalists and the political players they cover are professional adversaries. The idea of journalistic impartiality depends on it – so much so that media outlets have institutionalized the relationship across the country. The Globe and Mail‘s editorial policy reads as follows: “Reporters and columnists who routinely write on political issues must avoid being identified in their private lives with any party or political tendency. They are barred from most political activity other than voting. The same goes for editors who direct political coverage or take part in news selection and for everyone listed on the masthead.” Political activities such as campaign contributions, party memberships, marches, demonstrations, lapel buttons, lawn signs and campaign work are out.

Chin agrees with the stringent rules regulating a journalist’s political concerns. The moment a journalist is approached by a political party, he says, is the moment a journalist must declare the possibility of a conflict to his or her employer. Others would say it is only a conflict once the decision to leave has been made. While it’s blurry just where the conflict begins, clearly it’s not acceptable to do both. “You can’t suck and blow at the same time,” says Steve Paikin, TVO’s Studio 2 co-host and moderator of the English-language debate during the last federal election campaign. “You have to be one or the other.”

The line in the sand hasn’t always been there. In the years leading up to Confederation, the pursuits of politicians and government were inextricably linked with those of journalists. John A. Macdonald and George Brown both founded and subsidized newspapers to spread their political messages. Eventually, however, newspapers cut their ties with political parties, and their journalists became neutral observers of their surroundings. Still, reporters continued to fraternize with the politicians they covered on a regular basis: they played cards together, they ate dinner together and they drank together. It’s even rumoured that some journalists worked for politicians on the side. While hosting a CBC supper-hour show, long-time Star national affairs columnist Richard Gwyn wrote speeches for Eric Kierans, the former postmaster general, during Kierans’s unsuccessful bid to become leader of the Liberal Party of Canada in 1968.

This past summer, former prime minister Brian Mulroney claimed (through spokesperson Luc Lavoie) that Peter C. Newman wrote the speech he delivered to delegates at the 1976 Progressive Conservative leadership convention. Newman, who was editor of Maclean’s at the time, denies the claim. “The fact is I didn’t write it, and if I had, it would have been a lot better speech,” he told the Toronto Sun. “His people were writing the speech, and we [Newman and two other journalists] read the speech but we certainly didn’t write it or suggest how it could be changed.”

By the 1970s, however, relations between politicians and journalists began to cool. South of the border, events such as Watergate and the Vietnam War revealed widespread political malfeasance and reinforced the need for journalists to represent the public as watchdogs. In Canada, journalism became increasingly professionalized as more practitioners were taught a strict code of ethics by journalism schools and professional associations across the country. The friendly culture was slowly replaced with a confrontational one. The new wisdom saw politicians no longer as chums, but as adversaries. Working for a politician wasn’t done on the side anymore, and journalists were required to make a choice.

The rules of engagement changed over three decades ago, and the us-versus-them culture remains. That said, it hasn’t stopped journalists from giving political life a shot, and politicians and political parties are welcoming them with open arms. Success in modern-day politics has become largely a matter of fashioning an effective communications strategy. It’s commonplace for politicians at all levels of government, from policy boards to campaign teams, to employ communication specialists. During a panel discussion at Massey College in late October last year, Robert Hurst, president of CTV News, estimated that when special interest and lobby groups are included with politicians and bureaucrats, there are thousands of people working in Ottawa alone whose sole responsibility is to promote their employer’s message to the press. Who better than journalists – who retain an intimate knowledge of how media work – to do that?

As the political machine creates opportunities for journalists, the industry turns its back on its own. Statistics Canada’s most recent census shows that there were fewer working journalists in 2001 than ten years earlier. The situation has not improved since then. In fact, many journalists will argue the situation has deteriorated even further alongside the growing concentration of media ownership. Reporters who last ten or more years are anxious to move on, but like most market-driven industries, the journalism hierarchy is bottom-heavy and career advancement is competitive. It often leaves its senior practitioners feeling underappreciated.

“What distresses me is that journalism does not value experience in reporters,” says Star national affairs writer Graham Fraser. “The reporters who have crossed over into politics are journalists who have found that their employer does not want to take advantage of their broader understanding of the political and policy world that they’ve been covering. Thus, the idea of moving to a job where their experience will be recognized and valued – and where they will actually learn more about politics and policy – becomes irresistible.”

For Ontario Liberal MPP Jennifer Mossop, the prospect of moving into politics was, at first, far from irresistible. “I didn’t want that life for all the tea in China,” the former CBC Newsworld anchor and columnist with The Hamilton Spectator remembers thinking when she was first approached to run for office in 2002. She was, however, intrigued. Mossop got pregnant shortly after the meeting and, nine months later, delivered a baby girl. After her daughter was born, the Liberals approached Mossop a second time about running for the provincial legislature. This time, she said yes. “Journalism is great because you’re in the front row of all the action,” she says. “It’s like being at a boxing match – you’re so close, you occasionally get a little blood sprayed on your face. But being actively involved in politics is like being in the ring. You risk getting your nose broken and bloodied, but you’re doing it in the context of something you really believe in.”

That a journalist, after years as a neutral observer, wants to get off the sidelines and participate is a common refrain. For some, the evolution is natural. For the two decades Mossop was a journalist, she believed her value was to “sensitize” the public about an issue and arm it with a sense of empowerment they could use to do something about it. But the years passed, and stories like the tainted water scandal in Walkerton, Ontario and the shooting death of native protester Dudley George at Ipperwash Provincial Park in southwestern Ontario still happened. She says, “I didn’t feel it was enough anymore.”

Journalists may often think about leaving the profession, but leaving it to work in politics makes it hard to come back. Take Giles Gherson, editor-in-chief of the Star, Canada’s largest newspaper. He’s one of the lucky ones who left but managed to find his way back without damaging his career. In 1994, Gherson accepted an offer to become principal secretary to Lloyd Axworthy, the Minister of Human Resources Development in the Jean Chrétien government. Gherson’s main task was to coordinate the government’s transformation of the social security system, which included the design and implementation of a revamped employment insurance system.

Before taking the job, Gherson had been writing a political column in the Globe, one he had taken over from Jeffrey Simpson, who was at Stanford University in California on a Knight Fellowship for a year. When Simpson returned, Gherson found himself the odd man out. “I didn’t see anything that was challenging,” he says, “and the job in Axworthy’s office seemed like a really interesting way to test my assumptions about government.”

After two years of working for the Liberal government, Gherson was ready to resume his journalism career. His former employer, the Globe, was willing to take him back. But, even before Gherson left for Axworthy’s office, the paper’s editors told him he wouldn’t be able to go back to the Ottawa bureau once he finished working on the inside. They suggested that instead, he could write about sports or some other topic unrelated to politics. That didn’t sit well with Gherson – he respected the viewpoint that journalists, first and foremost, should be non-partisan observers – but rather, it’s a faulty assumption, he claims, that returning journalists will automatically shill for their former political employer. He worked for a Liberal member of Parliament, but he says he never considered himself a partisan. He was committed to a policy, not a political party. Besides, Gherson adds, “To work in government is not to love it.” Witnessing a dysfunctional government up close gave his writing a hit of realism. “I don’t think anybody said I was a huge friend of the Liberals after I came out.”

But if the Globe didn’t want him writing about politics, Gherson still landed on his feet. He was hired by the former Southam News Service to write a national economics column. In fact, he was offered the job because Gordon Fisher, Southam’s vicepresident of editorial at the time, considered his experience in government an asset.

Gherson was later promoted to Southam’s editor-in-chief, and eventually he made his was back to the Globeas editor of Report on Business, where he stayed until August 2004 when he made the jump to the top job at the Star.

Gherson’s success is the exception that proves the rule. For the most part, journalists who come back rarely get the chance to cover politics again. When partisanship is openly displayed, it’s a more difficult transition – something Michael Valpy knows well. The former Globe political columnist ran for the NDP in the 2000 federal election. He recalls being the subject of harsh criticism from colleagues from the outset. “Michael Bate, the editor of Frank, went around giving speeches about my betrayal of journalistic values and journalistic morality in having run.”

Valpy lost the election and came back to the Globe. He was offered the same deal as Gherson: anything but politics. But unlike Gherson, Valpy accepted and started writing a column on religion. Six months later, a position as a Queen’s Park columnist was posted and Valpy applied. “I was told there was no way.”

Valpy has written hundreds of articles since then, but only a few have been about politics. They include a feature profile on a youth voter named Chandler and a retrospective on the 1972 federal election – general interest pieces that Valpy agrees have little hard news currency. So, even though the “laundering” period seems to be over – recently he’s been filing more substantive political coverage – he also knows he may never be able to “sanitize” his political past. Asked whether he’d be hired to a political bureau in the future, he replies, “I’d be inclined to say I don’t think so. Once you’ve declared a party affiliation, that’s not forgotten.” While he misses writing a political column, he believes he doesn’t have much to offer. “What would I be bringing to the Globe other than somebody identifiably left, writing a left column? I couldn’t be the same political columnist as before because I’d be seen as someone who is making the left pronunciation of the day. I mean, I still carry my NDP card.”

As TVO’s Steve Paikin describes it, the divide between journalists and politicians is one that will never be bridged to anyone’s lasting satisfaction. “This is going to sound presumptious,” he says, “but journalists think of themselves as working for Team Public – not Team Liberal, not Team Conservative. And once you leave to play on another team you – fairly or unfairly – have ceased being a member of Team Public.”

It seems like an awfully hard line. CBC’s Keith Boag believes knowledge mined on the political side of the fence brings tremendous value to the public debate. “We have almost none of that in Canada,” says Boag, who would like to see more. “In the U.S., it’s quite common and with considerable benefit to the craft and the political dialogue.”

Many others including the Star‘s Chantal H?bert agree, as long as the welcome back is reserved for point-of-view positions like columnists. The idea of a reporter with partisan ties is, for most journalists, a bad one. If you used to read the six o’clock news and left to work in politics, Paikin says, you can’t expect to get your old job back.

Gherson, however, says his time in government gave him an understanding of the “flavour and texture” of the political and policy processes that you can’t get anywhere else. “My view was, now that I really know about government, you don’t want me writing about it. When I didn’t know about it, it was fine. I mean, we’re in the business of communicating to people, and we’re really saying, ‘You know what? You know too much. Oh, we don’t want our readers to know the reality.'”

Wherever the line is drawn, the debate isn’t going away soon. Reporters continue to leave newsrooms for politics, and political parties continue to hire them. For those who attempt to come back, the opportunity to cover politics again is unlikely – but not impossible. On February 1, 2006, Valpy’s byline (albeit, shared with two others) showed up on page one of the Globe beneath a report speculating on a same-sex marriage vote expected in the House of Commons. It’s just one in a growing list of political news stories to which Valpy’s name has been attached over the last several months.

As for Chin, he was busy making political news of his own in February. He resigned his position in the premier’s office and accepted the Liberal nomination for the March 30 by-election in the riding of Toronto-Danforth. If he wins this NDP stronghold, he’ll have proved his political worth, at least until the next provincial election. If he loses, Chin won’t return to journalism. He vows his reporting days are over. “The only way I could go back into journalism is as a Liberal commentator,” he says. “Not that that’s what I want to do.”

David J. Pett was the Senior Editor for the Spring 2006 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.