Chain Reaction

Bullied by the giants, the little weeklies are counting on their small-town savvy

Rick James walks through the century-old, red-brick building that houses his weekly newspaper, The Canadian Statesman, and describes what it looked like in days past and what it ‘ll become in the days ahead. In one room, pages for the following day’s edition of the weekly paper lie on the light green veneer of drafting-style tables, waiting for columns of print to be pasted in the newshole. Just over 20 years ago, the space would have been used by men casting “pigs”-tablets formed using molten lead-to print the pages. Soon, the now quiet, tidy room will be transformed again. “This is an area that will be eliminated in the next five years or so,” says James, who acts as publisher and co-owner with his father, John. He explains how the Statesman is converting its layout process to electronic pagination. Even the darkroom faces extinction as new cameras begin to record their images on computer disks rather than celluloid negatives.

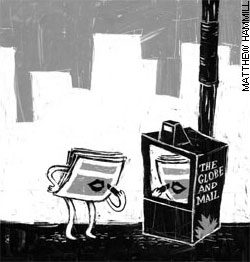

Adopting new technology and turning darkrooms into broom closets are musts for the country’s 400 or so independent papers if they hope to survive the rapidly changing landscape of weeklies. Now more than ever, they are fighting for their lives against rising costs and voracious newspaper chains, as groups such as Metroland in Ontario and MetroValley in B.C. take over more and more markets.

Like other independents, the Statesman is making changes to remain competitive, but for one of the oldest newspapers in the country, change and tradition become a tricky balancing act. It currently sells 6,500 papers each week in Bowmanville, a community of approximately 17,000 people a few minutes east of Oshawa, Ontario. For 75 cents, readers get reports from their MP and MPP, local hard news, sports, features, a front-page “Stork Market Report” and lots of grip-and-grin photos. James fears that tampering with the look of the paper could have repercussions with the readership. “The Canadian Statesman has always had the image of a 141-year-old paper: credible, can be trusted,” he says. Even today, the broadsheet’s banner has the same Old English type-face it had last century.

The old-fashioned banner isn’t the Statesman‘s only link to the 19th century: Rick James’ great-grandfather, Moses, a schoolteacher, bought the then four-page weekly from a local Congregationalist minister in 1878, and the family has run it ever since. The latest James publisher, now 37, began helping out by taking pictures and doing other odd jobs when he was eight. He came back to the paper in 1980, after graduating from Queen’s University with a degree in economics. Working for a newspaper with a staff of only 30 people, he quickly learned every aspect of the business, from operating the offset press to purchasing the newsprint. “That’s one trend in this industry,” he notes. “There are very few of my type left who have grown up with it and know every area of printing, newspaper, advertising, circulation. It’s almost like people are graduating from hotel management and being shipped into running a newspaper-one piece of a newspaper.”

These new-style, all-business publishers are common at chain-owned newspapers such as Metroland’sClarington This Week, which started landing on every doorstep in the Bowmanville area two years ago. Metroland, formed in 1981, is owned by the same company as The Toronto Star. It publishes 32 newspapers across southern Ontario in communities including Mississauga, Peterborough and Kingston. In some cases, papers for neighbouring communities carry the same advertising and similar news content. About the only things that distinguish Oshawa This Week from Clarington This Week, for example, are the front pages. Besides being able to economize on overhead costs, Metroland and other, similar chains can sell advertising space for several markets at once and offer attractive multipaper rates. The appearance of Clarington This Week didn’t affect the Statesman‘s circulation, nor did it steal away advertising clients, but finding new clients has become more difficult. Metroland can provide large advertisers with deals for ads in several, if not all 32, of its newspapers, including Clarington This Week. Meanwhile, selling space to national advertisers is getting harder for the Statesman and other independents. As James describes the problem: “We go in to this guy [at a large company] who doesn’t know Bowmanville from a hole in the wall.”

The Statesman gets some large advertisers with the help of the Ontario Community Newspapers Association’s ad sales division, AdReach, which acts like a chain by offering national ad space in the association’s many independent papers. But James’ paper is also fighting back on its own by selling advertisers on the paper’s roots in the community and the loyalty of Bowmanville’s readers. It’s an argument that, so far, has convinced the Statesman‘s larger accounts, including the Morris Funeral Chapel. Owner Paul Morris decided against moving his ads to Metroland’s This Week papers because he didn’t have confidence in the free papers’ readership. “Why would I want to advertise in a paper that’s thrown on my driveway?” he asks. “I’d have to wait until spring, when the snow melts, to read it. Rick’s paper is creative and informative, and it’s not page after page of advertising.”

Much of the responsibility of retaining readers falls on the shoulders of Peter Parrot, editor for the past 10 years and reporter for a decade before that. He believes the Statesman‘s community coverage will continue to set it apart from Clarington This Week. “A lot of the larger, chain papers really skim the surface of what’s going on in the community. They try to get one or two photos, one or two major stories out of the police, the council, the fire department, whatever, and then essentially the rest of the paper is filled with whatever news releases that come in and advertising. We get a lot of phone calls from people in the community who tell us what they think the news is that week: ‘Hey, we’ve got a new minister at the church, we’ve got a new president of our Rotary club, we’re going to be holding a fundraiser for the hospital.’That doesn’t mean we’re ignoring the big stories for the barbecues. We’re doing both.”

The James family’s connection with the community doesn’t hurt the paper’s reputation, either. Moses was mayor of Bowmanville in 1903 and 1904, and John represented the local riding as a Liberal member of Parliament for eight years shortly after World War II. Recent letters to the editor are sometimes informalIy-and incorrectly-headed “Dear Rick.”

However, the Statesman‘s reputation and image are becoming increasingly expensive to maintain. Newsprint has more than doubled in price during the past two years?a staggering blow to an industry where printing normally represents half of a cornpany’s costs. “It has not been easy to pass those increases on to advertisers,” says Michael Anderson, executive director of the Canadian Community Newspapers Association. “A business that is only growing by two percent a year will have difficulty accepting a five-percent rate increase.”

Common strategies for dealing with higher paper costs include reducing the size of pages but charging the same rate for small ads because they take up the same percentage of space. “It’s like giving a smaller chocolate bar for the same price,” says Duff Jameson, CCNA president and an owner/publisher in Alberta. Last spring, Jameson changed his St. Albert and Morinville Gazettes from broadsheets to tabloids to save on paper. He also purchased 15 other community papers in the past year to attract advertisers with his own minichain.

James has also considered expansion. He and his father launched The Clarington Independent, a small weekly delivered free to the municipality’s 19,000 homes, 19 years ago. Next, they may start another weekly in Oshawa. But James has already rejected the possibility of shrinking the Statesman‘s size as a cost-saving measure. “It’s an image question,” he says. “My wife knows nothing of the newspaper industry, but she said, ‘No, you have to stay a broadsheet like the Star and The Globe and Mail just to carry that image.’ You go to a tabloid and it loses some of that credibility.”

Ellen Schaffeler, a 17-year resident of Bowmanville, understands James’ reluctance to change the paper’s appearance-the traditional broadsheet format is what distinguishes the Statesman from the areas other papers. “It’s always been the same,” she says. “I don’t think people would like it as much if it changed.”

James doubts that shaving an inch or two from the width of a paper that is printed only once a week would save very much. Instead, he increased the Statesman‘s price from 65 to 75 cents and managed not to lose any readers. The Jameses also traded a fraction of the news space for advertising. James says such a move is extremely delicate because readers may frown on the reduced news content. He has managed to avoid laying off employees, but attrition has whittled the staff from 30 to 20 during the past seven years. So far the changes have kept the paper in the black.

Another subtle change to the paper’s image is a small addition to the front-page banner. In the lower-left corner, there now sits the Statesman‘s e-mail address. “Here’s the hell of anybody who owns a press,” James says as he waits for his modem to access the lnternet’s World Wide Web. “There’s still nothing easier to use than a newspaper, but we may be forced into electronic publishing by newsprint prices.” After a short delay, he toggles on a heading entitled “Oshawa This Week.” Seconds later, the screen changes and the words “Welcome to Durham News” spread across the screen, superimposed over a blue-and-green globe. The Statesman‘s on-line presence is currently limited to its e-mail address. Like almost everyone else, James wrestles with the problem of how to make money on-line. He sees the electronic newspaper as a way to complement the ink-and-paper version, offering additional information, longer stories that might not fit the paper’s format and self-advertising that might tempt the odd Net-surfer to buy a copy of theStatesman.

Whether or not the Statesman enters cyberspace by the turn of the century, it will undoubtedly retain its traditional elements as a connection to its community and readership. One more tradition it may want to hold on to is the work ethic exemplified by patriarch John James. The 85-year-old was too busy putting the paper to bed one production day last November to have time for an interview.