Comforting the comfortable: Dylan Farrow, Woody Allen and The New York Times

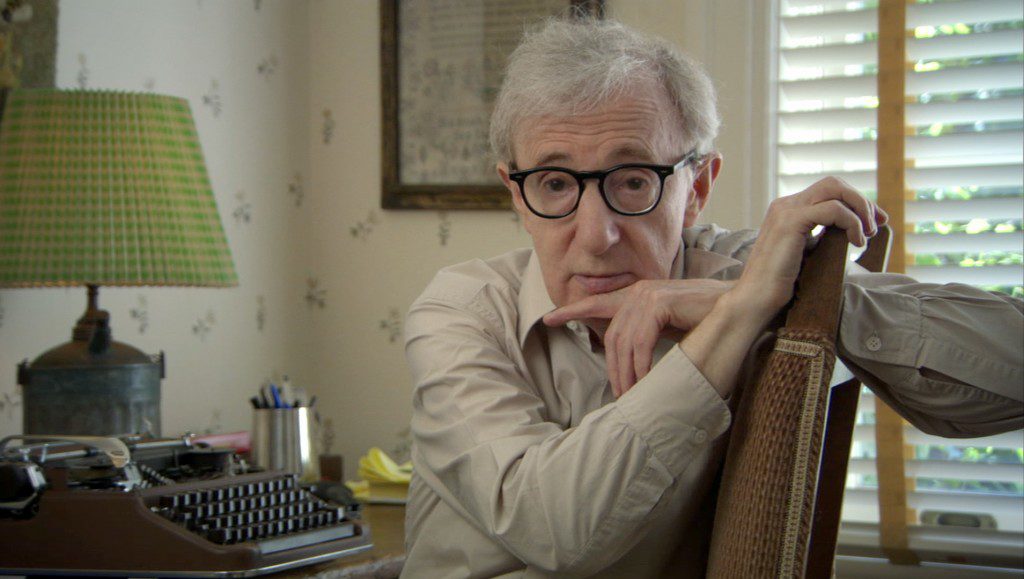

Image via Fansided.

By Aya Tsintziras

I was standing in line at the movies recently with a friend when she mentioned she still wants to see Woody Allen’s latest movie, Blue Jasmine. All I could think about was Maureen Orth’s November 2013 Vanity Fair piece on Mia Farrow and her children—specifically, the allegations that Allen sexually assaulted Dylan Farrow, their daughter.

As it turns out, this would become big news a few weeks later. When Dylan wrote her “open letter” for Times columnist Nicholas Kristof’s blog on February 1, she began it this way: “What’s your favourite Woody Allen movie? Before you answer, you should know:” before telling her story. I thought she was brave. Others did, too, includingGirls star Lena Dunham, who took to Twitter and other media outlets to defend Dylan:

To share in this way is courageous, powerful and generous. Please read: http://t.co/RKKREFB8hM

— Lena Dunham (@lenadunham) February 1, 2014

But it didn’t end there. When Allen wrote his own Times piece on February 7, he put a larger journalistic debate into motion: should a prestigious newspaper be a space to air one’s personal issues?

Orth wrote her February 7 follow-up, “10 Undeniable Facts About the Woody Allen Sexual-Abuse Allegation” because, as she explains, she wrote two “heavily researched and thoroughly fact-checked” Vanity Fair articles in 1992 and 2013 on the subject. While the truth of the allegations has of course come up for debate (Allen was investigated, but not charged, when the allegations first surfaced 20 years ago), there is a second discussion over why Dylan’s piece ended up on Kristof’s blog: Politicosays the Times editorial department rejected the letter before Kristof picked it up. According to Politico, the piece was published where the paper “felt it was most appropriate.”

There’s another layer to that story—one that I believe sheds light on whether this really was the most appropriate place for the dueling letters. In 2004, Steven Hatfill sued Kristof and the Times for libel, after the columnist implied that he was a suspect in the 2001 anthrax attacks. (The suit was dismissed, but Hatfill received a multimillion-dollar settlement from the government, who had leaked the information to Kristof and others.) Reflecting on the controversy in an August 2008 column, Kristof wrote, “The job of the news media is supposed to be to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted. Instead, I managed to afflict the afflicted.”

When he posted Dylan’s letter on his blog, he was definitely afflicting the comfortable and comforting the afflicted. He was right to give her the space to voice her truth. But the Times’s decision to allow Allen to respond was only comforting the comfortable. As Dylan says, she’s lived her whole life with others praising Allen’s films, and the director has long been able to bankroll a robust (but questionable) defence against Dylan’s allegations: Orth writes that Allen hired private investigators to look into state-police detectives who investigated Dylan’s claims in the early 1990s.

Kristof’s 2008 column looks at the balance between the public’s right to know something and respecting someone’s privacy, and both those issues are at play here. Allen is undeniably a public figure; Dylan just happened to be adopted by one. And that is an important distinction.

Remember to follow the Review and its masthead on Twitter. Email the blog editor here.