Community Disservice

Almost 14 years after Dudley George’s death, reporters still have a lot to learn about reporting on First Nations. Laura Janecka asked Peter Edwards, who covered Ipperwash, why the media got it wrong, and what reporters need to do to get it right.

Peter Edwards had two choices on September 6, 1995, he could either cover a story about a line-up for swimming lessons at Mel Lastman Square or he could drive to Ipperwash Provincial Park to investigate the shoot-out between police and First Nation protestors. Edwards chose the park. If it turned out to be nothing, he would just go home.

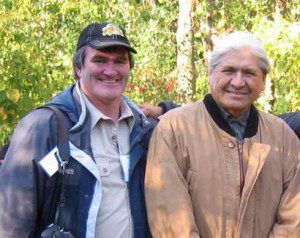

Instead, for the next 13 years, Ipperwash consumed theToronto Star reporter. During a night raid of Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nations’ protest to reclaim land appropriated by the government in the early 1940s, a police sniper shot protestor Dudley George. The shooter was convicted in 1997 of negligence leading to the death of an unarmed man, yet the penalty was only community service. George’s family filed a lawsuit, and an inquiry into the death, advocated by Dudley’s brother Sam, took place in 2003. Edwards wrote several hundred articles on Ipperwash and, in 2001, published One Dead Indian:The Premier, the Police, and the Ipperwash Crisis, an examination of the role of the OPP and the provincial and federal governments in George’s death.

Edwards spoke to the RRJ Online about his experiences covering Ipperwash, recent coverage of First Nations communities and lessons the media still has to learn.

On the media’s misrepresentation of Ipperwash:

Peter Edwards: [When I arrived,] the first thing that really hit me was the 100 or so First Nations people there-they were really, really nervous. I was the only white person and I stood out with these two cameras on my shoulders. I was curious about the reaction and how, very quickly, people decided that I should be standing out front, because the police won’t shoot a white person from the Toronto Star.

What I was hearing on the radio wasn’t what I was seeing. If [the protestors] have guns and they’re so threatening, why are they so afraid? And why are they thinking the safe thing to do is have a white guy floating around front? [The radio broadcast said] it was an “isolated incident” but when I got there it looked more like a military operation. I remember being really rattled when I saw someone with camouflage paint on his face and a camouflage uniform, with a submachine gun, running around in the woods -and that was the police’s side!

On media arrogance and ignorance:

PE: I was stunned at the deep level of racism…. I don’t know how many times I heard the phrase “thoseIndians.” The idea that people can, out of convenience, make all First Nation people the same is pretty arrogant and pretty dumb. It’s about keeping the [story and its facts] from going beyond what you absolutely know. People aren’t just a bunch of statistics. If someone is breaking the law in a particular community, don’t just target the community-and don’t say those. Sometimes we can subtlety put race in there so much that we slam a whole bunch of people when it’s really only one individual.

On covering the unfamiliar:

PE: When it comes to communities, we have to report beyond crises; we’ve got to talk to people on a day-to-day basis, not just when something terrible happens. It’s not that you can’t write the story, its how you write it. You can’t just quote the first person you talk to-you have to poke around the community to get a broader look. You can’t just take one person and make them a representative for everybody. In fact, some of the people we should listen to more are the ones that don’t shout or aren’t slick, but speak from the heart. We should look for those people instead of the smoothies who have a need to be in the media.

On representing a community:

PE: One thing you find with First Nations reporting, a lot of people will speak for themselves, but they won’t speak for the community. There’s a lot of sensitivity in the community-you wouldn’t speak for your mother or father, and you don’t overstate your own importance. With one kid who knew a lot about what had happened at Ipperwash, the way to get him to talk was to talk to his parents. Once I did, the kid became totally co-operative-without the parents, he wasn’t saying boo. There are real cultural differences, like respect for elders, so every time you do a story, it’s a fresh challenge.

On the media’s suggestion that members of the Yellow Quill First Nations community want Christopher Pauchay-the Saskatchewan man whose two daughters froze to death on the reserve-to heal through traditional practices instead of going to jail:

PE: I would want to know, and I’m not criticizing, which members? Because journalists can go into any community and find any opinion they want. I can find someone who believes Elvis is still alive and J.F.K. is working in a diner in Scarborough. You can find people to say whatever you want them to say, it’s just whether you’ve accurately represented the community. I don’t know whether they talked to a Chief, or social services-who work in the band with personal problems. If it’s someone who’s really in touch with things I would take it very seriously, instead of a person that’s just being flippant.

On advice for covering First Nations:

PE: There are still failings, there will always be failings in everything [the media] does. The biggest thing is to listen, listen to as many people as you can and stay open. Just remember that your job is to go and find the truth.