Drawing the Line

There are many subjects writers can discuss in the The Canadian Jewish News. Criticizing the security policies of the Israeli government is not one of them

They had fire in their eyes and torches in their hands. They were young and furious. They wanted the world to know the depth of their anger toward Ariel Sharon, the Israeli Prime Minister who planned to withdraw troops from the Gaza Strip and close down the settlements he had once so actively encouraged. While such protests are hardly newsworthy anymore, there was something about this picture of right-wing Israeli teenagers that caught the eye of Mordechai Ben-Dat, the editor of The Canadian Jewish News (CJN). It wasn’t just the raw emotion on the protestors’ faces that would grab readers’ attention, thought Ben-Dat as he sat in his east-end Toronto office searching for a front-page photograph; there was also the sky above them – a gorgeous, crimson-rich Israeli sunset, a vivid contrast to the greyness of Canada in November.

After 10 years as editor of Canada’s largest Jewish newspaper, Ben-Dat has learned, painfully at times, that he can never be too careful when choosing a cover photo – or anything else – for the publication. The weekly’s editorial guidelines state that, above all, a community paper should support the community it serves. As a result, the conservative Ben-Dat does his best to balance criticism with praise, good news with bad, bitter with sweet. Did the protestors’ at sunset strike this balance? Ben-Dat wasn’t sure yet, so he started to look at other possibilities for the cover of a November 2004 issue. Perhaps a peaceful picture of Israelis assisting Arab women during olive picking season? Or maybe a bloody shot from the latest suicide bombing? Or maybe a photograph of Tel Aviv’s blue skies and High Holiday lights?

A key part of Ben-Dat’s job is to deliver news about Israel as objectively as possible to a community that is anything but objective. For most of its 45-year history, the CJN has reflected what most Jewish people here think and feel about the Middle East. But no longer. In the past four years, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has become more complicated, and this country’s Jewish community more polarized. As a consequence, thanks in part to a recent wave of Israeli immigrants to Canada – many holding more radical political opinions than those in the established Jewish community – the CJN is now seen by critics as too timid, too bland. They argue that the paper is in need of in-depth investigations and debates about both Israeli policies and Canadian policies toward the Middle East at a time of major change in the region.

To his credit, Ben-Dat has been making some effort to present more analysis and to publish a greater diversity of opinions. But what dominates the CJN are pages of history, social news, and soft community features geared to its mostly 50-plus readership. It’s a focus that has prompted Lewis Levendel, the author of A Century of the Canadian Jewish Press: 1880s-1980s and a former CJN associate editor, to call the paper a “tranquilizer.” The challenge for Ben-Dat is to liven up the publication to attract new readers without alienating too many of the old ones. To do so means Ben-Dat may have to go further than he or the ownership group want. After all, this is a publication with a history of censorship and handcuffing writers with strict editorial guidelines. But it’s also a paper that, during its early years, was more than happy to criticize the Israeli government of the day, just as those Jewish teenagers were doing under that slowly setting sun.

He expounds briefly on how he views the paper: “We are a tabloid news format, but not a tabloid news mentality.” Ben-Dat then adds that the publication upholds “Jewish values” – values such as justice, sympathy, and respect. He likes to quote from a Tolstoy story, “The Death of Ivan Ilych,” about a man who worked hard all his life only to realize, on his deathbed, that he never had time to do anything of value – spiritual or meaningful. “Happiness is the feeling of fulfillment,” continues Ben-Dat. “Fulfilled was how I felt on my first day on the job.”

Ben-Dat is not only the paper’s editor, he represents its typical reader. He is 54, born and raised in Toronto, back when Yiddish was the language heard in his Jewish-immigrant neighbourhood, especially on Shabbes (Saturday), around the shul (synagogue). The neighbourhood kids were the children of recent immigrants and Holocaust refugees. For those youngsters, preserving the Jewish culture was a privilege their parents paid for in blood.

It was for this generation that the CJN was founded in 1960: the older, more conservative Jews who see Israel, according to S. M. Selchen, the former editor of a Jewish community paper in Winnipeg, as “the realization of a dream we bore with us for 2,000 years, and which was our hope and our comfort in the painful years of exile.”

The first owner was Meyer J. Nurenberger, a journalist who was born in Poland and later moved with his family to France and Belgium. He ran the paper as a private business. He insisted the CJN be independent and not a part of any Jewish umbrella organization, such as B’nai Brith. Under Nurenberger, the paper held controversial, right-wing views. He was a supporter of an Israeli party that opposed the 1947 United Nations resolution to create a separate Palestinian state. In addition, he attacked fundraising bodies and community institutions, including the United Jewish Appeal (especially for its secrecy in how it distributed its money), as well as the liberal Israeli government of the day. Following the death of his wife in 1970, Nurenberger sold the paper.

Today, in contrast, the CJN shies away from such confrontation. Ben-Dat prefers to highlight the kinds of dynamics the Israeli government must face, such as painful stories of the people, like that of Chezi Goldberg.

Goldberg grew up in the Bathurst Street and Finch Avenue area of Toronto, home to a significant Jewish community. Born in the early 1960s, he went to Jewish day schools; later, he served in the Canadian Armed Forces and studied at Columbia University in New York. Ten years ago, he moved to Israel. In Jerusalem, he ran a walk-in clinic for the homeless, the addicts, and the depressed. Living in a small town in the West Bank with his wife and their seven children, he arranged a special bus service for the community to get to Jerusalem. Goldberg missed it one morning and had to find an alternate route to get into the city and meet a family in crisis. That route led him to the No. 19 bus, on which he was killed in a suicide bombing.

Stories like this one, adds Ben-Dat, bring back a feeling of togetherness within the community as readers sympathize with the victims, know their names, and recognize their faces.

Carr believes the CJN, now a not-for-profit organization, still has an important role to play in the community. “There was a need [when it started], as there is now, for a paper that is independent, but has the welfare of the Jewish community in mind,” he says. The people in charge were to be motivated by public interests. The goal, according to Carr, is the “betterment of the Jewish community,” which he defines as giving information and knowledge to the Jewish community about the Jewish world.

“An informed community is a better community,” continues Carr. And to accomplish that, according to the CJN writers’ guidelines, which he helped compose, “It is not in specific language what constitutes ‘the community’s interest.’ The definitions may be as varied as the community itself, and the editor’s sensitivity and awareness will play a very important part in the maintenance of the necessary balance.”

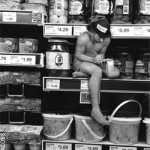

This was written in 1979, eight years after the CJN was purchased for, according to Levendel, $30,000 by a group of community leaders. Among them: Ray Wolfe, the head of several food distributing and supermarket chains (including IGA); Murray Koffler, the founder of Shoppers Drug Mart; and Albert Latner, a Toronto developer. Today, the weekly averages 60 pages in Toronto and 44 in Montreal – more if you count special sections like Food and Education. Revenue generation is not a big worry, but attracting younger readers is.

Lewis Levendel was an assistant editor at the CJN in the 1970s. He says many of the staff he worked with, such as Gary Laforet, the paper’s general manager, and Janice Arnold, one of the Montreal reporters, are still with the paper. “You get comfortable after 30 years,” he points out. “You’re not going to make waves.” To avoid their fate, Levendel left the paper in 1978 so he could travel.

“Mordechai has a certain style about him,” says Carr, explaining why Ben-Dat was made editor even though he had little journalism experience. “He was used to writing and was heavily involved in communal matters,” which, to the search committee, suggested commitment. “Sometimes you reach out, outside the industry, for somebody to be a leader.” Outside the industry is a reference to the fact that Ben-Dat practised law before taking over as editor. He graduated from the University of British Columbia and earned his law degree from the University of Western Ontario. He also worked at Queen’s Park as a justice and policy research analyst. While there, he wrote the occasional CJN editorial, on a freelance basis. “I would be making more money as a lawyer,” he says, “but this – this is love.”

And a challenge, particularly when it comes to targeting a younger audience. To try to get them, Ben-Dat has chosen to appeal to their interest in Jewish culture and entertainment – and to offer features about or by them. One example: Toronto-based filmmaker Igal Hecht, who produced a documentary titled Kassam about life in Sderot, a small Israeli town where in the past year residents had to deal with a daily barrage of missiles hitting them from a northern town in the Gaza Strip. In the CJN, Hecht wrote about some of the scenes in his film. One of them features a woman named Coty Malka and her daughter, Taeer, almost one year after a Kassam missile hit Taeer’s kindergarten.

As Hecht describes it, Malka remembers getting to the school all hysterical, passing little chairs and tables, and little finger paintings hanging on the wall until she finally found her daughter crying. Taeer wasn’t scared of the missile. She couldn’t find her best friend, Afik. Malka rushed to the backyard. She saw a huge hole in the ground. And she saw Afik.

Three-year-old Afik was still alive. He even lifted his head and looked around, recognizing people, wondering what was going on. His lips were swollen, and he was covered in blood. Half of his right leg lay there on the ground not far from the rest of his body. It looked so small.

Afik is dead now and Taeer has been sleeping in her mother’s bed ever since. She needs to calm her mom down every time there’s a loud boom outside the window. She tells her mom, “Mommy, it’s a rock, not a Kassam.” She still dreams of Afik. Only in her dreams “his back is all in one piece again.” When Taeer said that, Hecht admits that he “got emotional.”

“I’ve been to refugee camps,” continues Hecht. “I’ve been to suicide bombing locations right after the explosion, but when I talked to Taeer – that was the first time I’ve started crying during an interview.”

It’s a strong and compelling article, but in his quest for young readers, Ben-Dat is competing against Internet sites and publications such as the right-wing Jewish Tribune, put out by B’nai Brith Canada, and an independent Toronto paper called Afterword. Both of these competitors speak more directly to the interests of youth – most of whom are like me, one of approximately 50,000 people who have emigrated from Israel to Canada since 1980. We have strong bonds with the Jewish state and have had life-altering experiences there. I, for instance, served in the Israeli army for a year. I was also at the demonstration for peace, in 1995, at which Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a right-wing extremist. I was 14.

Right now, there are two publications that are aggressively courting my generation of expatriates, who are looking for links to and discussion about the country we left. The first is Shalom Toronto, a new weekly, written in Hebrew, which offers a crossword and news and gossip from the homeland. Each issue is 32 pages and has a circulation of 10,000 copies.

The other publication, The Jewish Magazine, is actually a decade-old monthly, but one with a fresh new attitude. Two brothers, Ori and Edan Sher, took over their father’s magazine early last year and revamped it. The layout is glossy and colourful; the content is both in Hebrew and English. It has a circulation of 16,000 with an average of 56 pages per issue.

Edan says their dream is to become bigger than the CJN, and to help him and his brother achieve that goal, he’s stressing their Israeli coverage. They know the country better than the CJN editors do, explains Edan. The brothers are former Israelis, and they had front-row seats at bombings. They had to deal with destruction and had to fight for their lives. They feel like they’ve earned the right to criticize, and so they’re happy to publish a spectrum of views from regular columnists writing from Israel. The goal, says Edan, is to encourage controversy – to spark a debate on issues ranging from Palestinian rights to Sharon’s security fence.

Contrast this with the CJN’s perspective on covering the Jewish state: “The security of Israel is Israel’s business,” states the paper’s editorial guidelines. “We do not live there.” As a result, the CJN will not judge or criticize the Israeli government’s stance on security. Ben-Dat is more at home exploring “rich Jewish history” in his editorials. As well, his columns are often dedicated to the great rabbis and their words of wisdom, to adventures and journeys of famous Jewish figures, and to Jewish literature. They are never personal. If he’s telling a true story, he will refer to himself in the third person.

It’s an approach that does resonate with some Jewish youth. “I grew up on the CJN,” explains Dave Silverberg of Afterword. “And I still read it front to back every week.” He says the CJN inspires him, makes him feel a part of a community, and he gets to see his friends in the snapshots of the back pages that are dedicated to birthdays and weddings.

To other 20-something Jews, however, community events are not enough. Sharon Furman, a columnist for the Jewish Magazine, feels that the CJN, while doing a great job for its core Jewish community, could be so much more. “They should bring in more controversial pieces,” he says. “I, for one, would love to be provoked.”

Kirshner has been with the paper for more than 30 years. For a guy who started in Oakville, Ontario, as a technical writer with no journalistic training, he’s seen a lot. He’s been called an Israeli spy in Syria. He’s toured Southern Lebanon in 1983, when Israel occupied it. He’s walked along the train tracks that took Europe’s Jews to Auschwitz. He’s interviewed Arafat in Gaza during the Oslo period. When he first started writing for the CJN, the liberal Kirshner regularly had his copy changed. Even a decade ago, his columns and analyses were censored, says Levendel. Why? Because the CJN’s writer’s guidelines “limit editorial freedom.” They were created after the 1977 elections in Israel; following that vote, won by the right-wing Likud party, the paper was bombarded with letters from both individuals and organizations when it criticized the new Israeli government. Just as today, there was great concern about the settlement movement. One CJN editorial, titled “Compromises Required: True Nature of Peace,” even called for the dismantling of settlements and for Palestinian self-determination – exactly the kind of critical perspective that those dissatisfied with the CJN would like to see more of.

As a newspaper supported by community funds, states the CJN guidelines, the publication “cannot maintain that degree of freedom that is the stated goal of commercial general newspapers. Freedom of the press has to be balanced by the recognition that the paper must make every effort not to damage the community’s interest.” In other words, it means celebrating Israel, not criticizing it. Though, says Kirshner, writers have far more liberty now than they once did. “[We are] more free, there is more room than ever to write one’s opinion. Having said that, however, the paper will never accept a column where I would say, ‘Israel is a binational state.’ There are certain parameters everyone lives according to.”

Ever since the second intifada started, he’s heard the voices speaking out against the Israeli government, whether for being too tough on the Palestinians, or not tough enough. He claims there is room for most of these voices in the CJN.

“It’s like a Passover fable,” he says, referring to a story about four sons getting together for the holiday dinner. The name of one is the Wise, who knows all the rules and follows them; one is the Naïve, who is not yet experienced with all Jewish laws; the third is the Immature, who is too embarrassed to ask about the rules and obligations and, therefore, cannot commit to them correctly; the last one is the Evil, since he refuses to understand what all these rules mean to the other Jews. The lesson, concludes Ben-Dat, is that “there is room for all of the different types at the dinner table.” Except, perhaps, for the one known as Dissent.

“We write for an opinionated, well-read, not-reluctant-to-express-themselves community,” continues Ben-Dat.

And in his opinion, this community is a mirror image of the one in Israel. When dealing with this type of audience, he adds, it’s impossible to satisfy everybody.

But that doesn’t mean he won’t keep trying. Later in the production day he finds another possible cover picture. He’s not yet sure whether this is the one, but it is a testament to striking the right balance: it’s a photograph of two billboards, standing side by side on a Tel Aviv highway.

One of the billboards is white and blue, the colours of the Israeli flag. It reads: “The people have decided to get out of Gaza.” The other is in blood red and pitch black. A tear is painted in its middle and the text reads,”Sharon is tearing the people apart.”