Fear Factor

War is more dangerous for correspondents than ever before, says veteran CBC reporter Brian Stewart. But while fear can be a liability on the front lines, it can also keep you alive

I’ve known foreign correspondents who confess to becoming so addicted to war, they feel lost without a new one to cover. Although I spent a decade in and out of conflict zones, I never had that problem. The Fear Factor, as well as aging, saw to that. It never caused me to flee a war or dodge an assignment, but I sometimes worried my work might suffer after repeated exposure to conflict. There’s no point in going into a combat area unless you can perform exceptionally well – you don’t risk your life to do mediocre work. So if you’re honest you ask yourself if you’re still willing to face the risk, and as dangers to war correspondents increase each year, so does the Fear Factor.

Much has been written about the unprecedented casualties among such journalists in the past decade. There are excellent studies now emerging about post-traumatic disorders suffered in the profession. However, relatively little has been written about how one’s professional edge may be worn down by the Fear Factor. I’ve seen a handful of cases where nerves cracked and journalists or crews fled the field. I’ve also observed legendary veterans of rock-solid nerves like BBC’s Kate Adie and CBS’s Alan Pizzey – men and women who survived decades of wars and are still anxious to go where fighting is fiercest. I sympathized with the former, admired the latter, and increasingly sought to keep in the hazy middle ground. I would run what I calculated were acceptable risks, and a few times even bet my hide for exclusive coverage. But between the ages of 30 and 40, I saw enough and felt enough to lose any taste for heroics.

When I first covered wars in Central America and Lebanon in the 1980s, I went with a sense of adventure and purpose. I even found my first experience of lying in a ditch under mortar fire more fascinating than fearful. My innocence, like so many, was in believing that professional skill and common sense would be adequate armour for what lay ahead. In his 1932 masterpiece Death in the Afternoon, Ernest Hemingway was fascinated by the matador Cagancho, who was terrified of bulls, but had such faith in himself he felt invulnerable in the ring. In the early ’80s many of us were like Cagancho: ready to acknowledge fear, but dependent on survival skills and luck to see us through most circumstances. However, as journalistic casualties rose, we learned that no amount of skill guarantees survival.

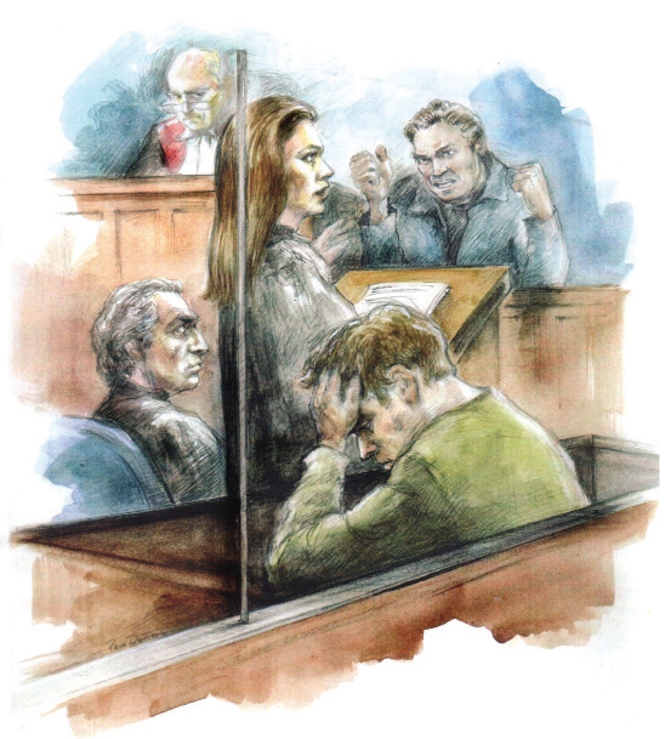

Reporters I’d most admired began falling like rookies: in Beirut, Lebanon, the Associated Press’ Terry Anderson was the poster boy for the mature, war-smart survivor until he was kidnapped in 1985 for six years. The revered British reporter David Blundy survived 23 wars only to be killed in 1989 by two stray bullets in El Salvador. Since the mid-’80s, journalists have become targets. Teenage militia soldiers were ever more psychopathic; almost overnight, snipers and landmines were more commonplace and parcel bombs escalated to car bombs powerful enough to shred victims two blocks from a blast site. Moments of terror were usually brief. More common was the dread that could grind on for weeks: You dreaded seeing more human suffering, more dead children and mass graves, even though you knew it was critical to bear witness. You hated the mind trips that plagued war zone travel: Why were their no children playing outside and no farmers working these fields? Was this the same road a Norwegian crew was murdered on? Is that the same van in the rear mirror we saw yesterday? There were also moments of moral choice.

Deep in the El Salvador countryside, refugee families begged me to stay overnight, as my presence might protect them from massacre – but reporters were prime targets. I was still trying to think clearly when the last-minute arrival of a Red Cross team relieved me of the life-or-death decision. Canadian television reporter Clark Todd faced this same choice in Lebanon in 1983. He chose to stay, and was murdered along with scores of villagers. And so I ask myself years later, what will I do the next time I’m begged to stay the night?

It’s not all fear – war coverage can be fascinating. In the Gulf War, I made it in with the first armoured column to liberate Kuwait City – one of those exhilarating moments young reporters dream of. But war is incomparably more dangerous for correspondents than ever before, and ultimately there’s a professional conscience to be faced: will there come a time when you’re not so anxious to beg rides to the front lines, or willing to drive through no man’s land to reach an isolated village? Will growing caution make you a liability? When I glance over mementos, I ask myself if I’d cover another war. I find no easy answer: perhaps if the issue is vital, and my daughter is older. But if I do go back, it will not be with illusions of Cagancho or with the innocence of youth. I’ll know the Fear Factor is waiting to test me afresh and perhaps more powerfully each time I head out.

This is a joint byline for the Ryerson Review of Journalism. All content is produced by students in their final year of the graduate or undergraduate program at the Ryerson School of Journalism.