Northern Contradiction

To most Canadians in the '50s and '60s, Edith Josie of Old Crow, Yukon, was the quaint insider from above the Arctic Circle. But to her fellow Vuntut Gwich'in, she was a strong voice for a better life

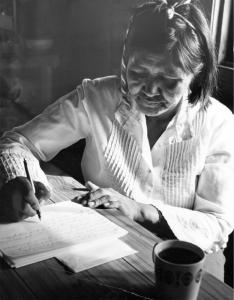

Josie was so revered in Old Crow that her kitchen-cum-writing studio remains just as she left it, almost two years after her death

Twice a month, Edith Josie lowered her five-foot frame into a chair at her large, plywood kitchen table with pen in hand. Looking out the window at other cabins, all raised on wooden pilings because of permafrost, she lit up a cigarette and started writing in longhand on foolscap with carbon between the sheets. “It is a very small village here at Old Crow, but the news is getting better every week,” she wrote in 1963. “Even now the spring has come cause it is daylight around 11 o’clock p.m. Pretty soon we won’t use light for night time. Everyone glad to see plane every day. Even the same plane come in one day, they all have to go down to see what is going on…. I’m sure glad everyone gets my news and know everything what people are doing.”

She mailed her dispatches from her fly-in community, 130 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle, to The Whitehorse Star, which published “Here Are the News” verbatim, despite the weird syntax and grammatical errors. Harry Boyle, her first editor, thought the mistakes just added character and it would be wrong to change anything. Her column, which ran from 1953 to 2005, was syndicated by larger papers such as the Toronto Telegramand the Edmonton Journal. It was translated into many languages—including German, Spanish, Italian and Finnish—and eventually collected in a book, The Best of Edith Josie.

Josie, who spoke two aboriginal languages and English, wrote the way she spoke, but her unconventional style—rooted in an oral tradition—resonated with readers. Despite her popular column, Josie’s own story is a contradictory one. She drew attention to her small community, but she also fed the idea of the North as quaint and charming, a desolate land full of heartwarming inhabitants in mukluks getting ready to compete in dogsled races.

Born in Eagle, Alaska, in 1921, Josie was a member of the Vuntut Gwich’in (People of the Lakes) and attended school until Grade 5. She became the Star’s Old Crow correspondent when the wife of the town’s Anglican priest turned down the job and offered it to Josie, who was unmarried. “Most of the ladies had someone to look after them,” Sarah Simon said. “Edith didn’t have a husband to look after her, so I gave Edith the job.”

Josie had a simple approach to her column. She once told Farley Mowat, who visited Old Crow in the ’60s, she focused on people, “hunting and fishing, and cut-wood they got for sale. And sometimes I write about old-timers like my mother.”

While she was always positive about the town and the people, Josie was honest with her readers, even apologizing for missing information: “Women dog sled race held today. Nine teams was in the race. Sorry the time sheet is lost. It was tack up on the post and the kids of torn it off.”

She liked it when fans of her writing visited her, but Josie did not want to be portrayed as property of The Whitehorse Star and believed her columns contributed to improvements to Old Crow and awareness of the need for better infrastructure in the town. According to a Globe and Mail report, she told off local boys who’d taunted her with the moniker “Whitehorse Star” by saying, “When I came here in 1940, people had a hard time and lived in poor buildings. When I write the news, from there your parents started getting new house. I write the news, that’s how Old Crow became better. So don’t call me ‘Whitehorse Star’ again.”

The boys in town were not the only readers to underestimate Josie. In a CBC North radio series called “Yukon Nugget,” broadcaster Les McLaughlin said that when he first read Josie’s writing, he thought, “It was kinda cute. Not very deep or insightful…just…well…just cute. But more than 30 years later, Edith Josie’s columns have become an important record of lives of the people of Old Crow.”

In 1965, Life sent reporter Dora Jane Hamblin to profile the columnist in a piece titled, “Everybody Sure Glad.” The dek read, “In the Yukon, Indian reporter Edith Josie wrestles with words to tell the news.” And the story claimed, “Most people start reading Edith just for the fun of watching her grapple with the English language and lose.” Hamblin argued that Josie’s work “evokes the stark stuff of life in the Far North.”

But Valerie Alia, author of Un/Covering the North: News, Media and Aboriginal People, spent time in Whitehorse and believes calling Josie’s grammatical quirks endearing is patronizing and that she was the voice of an important First Nation in a remote community. “Often, people think it’s just about quaintness and charm and northern landscapes,” she says. “But this stuff is also about political and cultural landscapes, North and South, and how they interact.”

Edmonton journalist Linda Goyette was in Old Crow writing a book when Josie died of natural causes in January 2010. Goyette, who attended the funeral, discovered the North through Josie’s writing in the mid-’60s in an overheated Grade 5 classroom in Lucknow, Ontario. A teacher wearing horn-rimmed eyeglasses tapped a wooden pointer at the top of a Neilson’s map of Canada and said, “See up there? That’s where she lives! Way up at the top of the Yukon!”

Goyette later realized that “Here Are the News,” though ungrammatical, was a more vivid depiction of life in a small northern town than southern reporters ever supplied. Supposedly more professional and accomplished, they tended to interview missionaries, priests, local RCMP officers, Hudson’s Bay workers and teachers, but not aboriginal people. “Her writing,” says Goyette, “challenged the prevailing southern notion of that era that any young outsider could drift into a community for a day or two and get the story right.”

She adds that at least Josie gave the North a voice back then. Now, quaint reporting has given way to dead air. “The patronizing or racist writing of colonial times seems to have been replaced with this vast, unacceptable silence.”

And Josie’s world was anything but silent. She bypassed Yukon caricatures and stereotypes that Goyette calls “The cremated Sam McGee and the frozen Mad Trapper, Hollywood Mounties and Klondike dance hall girls—all larger than life and full of bravado,” and she wrote about the life of a town and the people in it. Old Crow has changed, but ravens still seem to have personalities and dogs howl into the early evening as hunters make their way back from their river camps.

The remnants of the Anglican Church and its steeple overlook the Porcupine River, and 100 metres away, in Josie’s cabin, her infectious laugh seems to linger in the air, permanently clouded with wood and cigarette smoke. Yukon artist Jim Robb’s depiction of the cabin—with two ravens perched on the eaves and salmon drying on a rack in the sun—hangs above Josie’s kitchen table, just as it has for decades. In the drawing, the sign on the roof reads: “Miss Edith Josie. Grandma, storyteller, journalist, historian, community leader, Member of the Order of Canada.”

Samantha Anderson was the Online Story Editor for the Winter 2012 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.