Silence of the labs

Why the federal government's attempt to muzzle its scientists hinders public knowledge and damages science discourse in Canada

ENVIRONMENT CANADA SCIENTIST David Tarasick helped identify the largest ozone hole in the Arctic, and Postmedia reporter Mike De Souza has finally secured an interview in late October 2011, after almost three weeks of bureaucratic delays. Towards the end of the conversation, De Souza asks why the phone call took so long to set up. “Have you been extremely busy and not available to do interviews with the media?”

Suddenly, a woman’s voice cuts in, “Mike, it’s Renee here. David is here and available to speak to you now, so I think that’s kind of a moot point.”

“I’m asking the question and if he wants to answer it, he can answer it,” says De Souza.

“I’m available when media relations says I’m available,” answers Tarasick. “I have to go through them.”

Before 2007, when government scientists could respond to media freely and independently, this story would have seemed preposterous. But over the past few years, journalists have been dealing with a different set of rules.

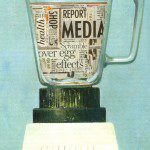

In November 2007, Environment Canada implemented new guidelines for its employees. The government rationale was “just as we have ‘one department, one website’ we should have ‘one department, one voice,’” the goal being to coordinate and consolidate the agency’s message. However, the new policy required practices such as getting media relations to respond or “asking the programme expert to respond with approved lines,” depriving scientists of their own voice on the subject.

This has been a trend throughout the Canadian government. The resulting interview delays and denials have had a significant effect on science journalism in Canada—an Environment Canada memo obtained by Climate Action Network Canada estimated the drop in access to government climate change scientists at 80 percent—prompting many journalists and scientists to speak out against the current government’s move towards opacity.

“What you’re looking at is the government trying to control the release of information,” says Stephen Strauss, president of the Canadian Science Writers Association. “If you’re looking for a bad return on your tax dollar, it’s hard to imagine a worse return than when you can’t find out what your own people have done.”

Science writers have reported delays lasting weeks, often with no interview granted or PR-scripted talking points sent to them via e-mail. In one memorable case in March 2012,Ottawa Citizen reporter Tom Spears submitted a freedom of information request to find out why, when he asked for an interview with a snowfall researcher, the National Research Council Canada (NRC) took an entire workday to send him seven sentences of information and an unrequested technical diagram. No interview whatsoever was given.

A month later, in reply to his freedom of information request, Spears received a 52-page document containing e-mails from numerous NRC media relations employees, debating what to say, why to say it and whether an interview was necessary. Bullet points were suggested, trimmed down, added to, sent to Spears and then disputed some more.

What nobody ever gave in this drawn-out nitpicking was a straight answer to Spears’ original request. He had simply asked to speak to someone about what the NRC’s involvement was in studying snowfall with NASA—which, by the way, responded quickly and had a scientist speak to Spears.

De Souza says he won’t comment on what he thinks of muzzling, but cites several examples of unusual actions taken by the government, such as inconsistencies in Environment Canada’s release of information—for example, putting out a press release when studies showed mercury levels in fish were not increasing, but keeping silent when similar research showed mercury levels in bird eggs were increasing. “Some studies are convenient and some are not, it would appear,” says De Souza.

JOURNALISTS AND SCIENTISTS ARE starting to make some noise in protest. On July 10, 2012, thousands gathered in Ottawa to mourn the “Death of Evidence,” holding a mock funeral for evidence-based political decisions—and citing a long list of infractions including scientific program closures and the muzzling of scientists. Lab coat‑clad protesters carrying signs and a symbolic coffin marched in a funeral procession to Parliament Hill, where the rally was held. After hearing from several speakers, the crowd watched as a dozen scientists contributed select books—such as Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species—to the coffin’s “body of evidence.”

The Conservatives’ response was swift and uncompromising. A media release, sent out on the same day as the protest, highlighted the government’s support of science and technology, but ignored the specific issues the protest raised.

Minister of Science and Technology Gary Goodyear released the statement, which said: “Our government is investing in science and research that is leading to breakthroughs that are strengthening our economy and the quality of life of all Canadians. Our investments are enabling Canadian scientists in universities, colleges, businesses and other organizations to help secure Canada’s prosperity today and into the future.” He also listed the many areas where science funding has increased. It did not explain the various program cuts and closures, nor did it mention the muzzling of scientists.

Ted Hsu, Liberal science and technology critic and MP for Kingston and the Islands, participated in and spoke at the rally. He’s heard this government response before. “Whenever we talk about muzzling scientists, in Question Period for example, the standard answer is, ‘We fund science a lot.’ And overall they do, but the funding is really focused on industrial-academic partnerships,” he says. “That’s not a bad thing. But it’s not a relevant answer to the question.”

Death of Evidence organizer Katie Gibbs, a recent PhD graduate who studied biology at the University of Ottawa, says federal silencing of scientists is unprecedented in Canada. “International bodies have been writing stories about what is happening in Canada because it is that shocking and that unusual,” she says. In fact, some protesters told Gibbs that they had first heard of the situation through those international sources, such as theGuardian’s Environment Network in the United Kingdom.

Postmedia science reporter Margaret Munro in fact broke the story before any international media outlets. Published in January 2008, a few months after Environment Canada enacted its media relations policy, Munro’s article, “Environment Canada scientists told to toe the line,” informed the public that government scientists were being muzzled.

“These stories on the muzzling have met international headlines; they’ve been decried within the scientific journals,” says Munro. “This has turned into a black eye for the federal government.”

But Gibbs wants more than the occasional reminder in the paper. “When you try to contact a scientist and don’t get an answer, write that up,” she says. “Make muzzling itself a story if you can’t get answers out of government scientists.”

Thomas Duck, an atmospheric scientist at Dalhousie University, notes that though covering muzzling is important, covering the science itself is still just as important. “Things like ozone holes, the public wants to know about. And there’s no good reason for the government to not allow that information to go out to the public,” he says.

Hsu, who has a PhD in physics from Princeton University, says he wants a well-informed populace and an open conversation within the scientific community. “Scientists don’t learn everything that somebody else did just by reading the research papers,” he says. “You need to talk, you need to ask questions. There needs to be a lot of back and forth to really understand a piece of scientific research.” Naturally, journalists also need this back and forth to better understand research, and to write informative stories.

“WHY IS THE MINISTER PUTTING A GAG ORDER on Canadian scientists?” asked Megan Leslie, New Democratic MP for Halifax in the House of Commons in April 2012. She was referring to an international scientific conference in Montreal, saying “in addition to top scientists from around the world, this year also features government babysitters assigned to follow Environment Canada scientists and record their conversations. Is this 1984 or 2012?”

Environment Minister Peter Kent, who was an award-winning journalist before becoming a politician, has defended his department’s media policy as “established practice,” stating the need for separation between the science and the policy that follows.

“Where we run into problems is when journalists try to lead scientists away from science and into policy matters,” Kent responded to Leslie. “When it comes to policy, ministers address those issues.”

In an interview with Embassy newspaper, Kent responded to the allegations of muzzling, defending his department’s media relations policy and saying the allegations come from “a very small number of Canadian journalists who believe that they’re the centres of their respective universes [and] deserve access to our scientists on their timeline and to their deadlines.”

He also said: “We do make our scientists available at times of mutual convenience for both themselves and the journalists who want to talk to them, but there have been a number of complaints which I think were quite unreasonable in terms of the timelines and the time frames of very few journalists.”

Several groups, including the Canadian Science Writers Association, Canadian Journalists for Free Expression and the Association des Communicateurs Scientifiques du Québec, responded with an open letter to the minister. The letter said the contributors expected that Kent, the journalist, “would have said that not only [is he] against it, but that if the muzzling doesn’t stop, [he would] be submitting [his] resignation to the Prime Minister.”

Hsu notes that Kent’s point is irrelevant since there are relatively few pure-science journalists in Canada, adding that the government would do well to pay attention when those few speak out. Kent was not available for an interview for this article.

AT THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION for the Advancement of Science’s annual meeting in Vancouver in February 2012, a panel discussion featured Francesca Grifo of the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) in the United States. She described the American experience during the George W. Bush presidency: “You name it, if it was inconvenient for either the government or a donor to [the administration], they suppressed it or manipulated it,” she said in her speech. She cited instances of blatant political interference in science, alluding to one case in which former U.S. Fish and Wildlife deputy assistant secretary Julie MacDonald made changes to the population data of an endangered species, but failed to erase the evidence left by the “track changes” feature on the document.

The UCS kept a database of such incidents and used it to pressure the United States government. It paid off when President Obama signaled a change in policy in his inaugural speech, saying: “We will restore science to its rightful place.”

Progress was not immediate, but it is being made. John Holdren, director of the Offi ce of Science and Technology Policy, now requires that government agencies create scientific integrity policies, including media policies. Political officials and bureaucrats are specifi cally barred from attempting to alter or suppress scientific findings and U.S. government scientists are free to speak to the media about anything, provided they make clear the distinction between their opinions and those of their organization.

“That’s totally different, and what that does is it gives the public a lot more confidence in the truth of what scientists are saying,” says Hsu. “If the scientists are speaking freely and their message is not being controlled by politicians, people trust it more.”

But is a similar change on Canada’s horizon? Strauss thinks people need to see a crisis fi rst. “It looks like the science writers are complaining that the policy makes their job harder,” he says. “The general public doesn’t care.”

What might need to occur, according to Strauss, is something terrible happening due to a lack of public knowledge. If a preventable environmental disaster occurs because the public wasn’t aware of the science behind it, people’s ears might prick up. “Then you’re not talking about an abstract,” says Strauss.

Duck says the loss of even a few necessary policies—especially concerning medicine and the environment—could negatively affect the health and safety of Canadians.

He won’t speak with scientific colleagues working within the government about muzzling for fear they might be punished.

“These are people who work very hard in the public interest. They work very hard to protect the environment that they know we all depend on,” he says. “I’m not going to do anything to compromise the work that they’re doing.”

About two months before the interview with De Souza, Tarasick had been given a “workforce adjustment letter,” which notified Tarasick that Environment Canada could cut his program’s funding. Kirsty Duncan, Liberal MP for Etobicoke North, said in the House of Commons that, if enacted, the cuts to ozone science would reduce Canada’s ability to monitor the environment and threaten its international reputation.

MARGARET MUNRO, THE JOURNALIST who first broke the muzzling story, thinks that Canada needs its own version of America’s UCS to band together and fight for transparency in government. “That group forced [the U.S. government’s] hand by keeping the pressure on,” she says. “And we don’t have a group like that here.”

Gibbs says she and her University of Ottawa colleagues are planning to start an organization with a focus on promoting evidence-based decision-making and watching the government in order to catalogue “examples of things that were particularly egregious,” like specific instances of muzzling or cuts to crucial scientific research programs. The organization would also organize events like Death of Evidence to increase public awareness of questionable government practices.

Organizations like this may improve public awareness, and it’s possible that public opinion will sway the current government from its position. The good thing, says Hsu, is that the issue is easy to explain. “I don’t think anything fancy is really required, just a lot of hard work,” he says.

For now, science reporters will have to continue working within the confines of the current system, conveying science to the public as best they can. “I can tell you, when Peter Kent was a journalist, he would not have put up with this,” says Munro. “That’s not the way the world of the media works. This is not timely access.”