So long, CanCon

The CRTC no longer requires etalk and ET Canada to cover Canadian entertainment news. But does that mean they shouldn't?

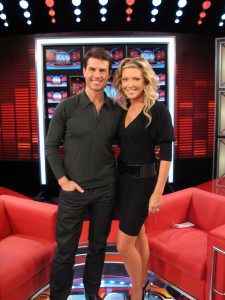

It’s a little after 11 a.m. when Cheryl Hickey enters the studio, all shiny blond hair and thick black eyelashes. Her petite, gracefully slender frame is wrapped in a knee-length, long-sleeved black dress that’s paired with opaque tights. She clicks onto the large, circular stage in black stilettos that are too big for her, she says, and assumes position. Staring into the camera, Hickey pats her long, tousled hair and awaits her cue.

A host on Entertainment Tonight Canada, Hickey is gearing up for another day of work at the show’s Toronto studio. The TelePrompTer rolls as she reads through the day’s headlines, called “links.” On this October morning, they include interviews with Orlando Bloom and Milla Jovovich for The Three Musketeers, Sandra Oh being inducted into Canada’s Walk of Fame, and, of course, the juice: the trial of Shania Twain’s stalker.

“What was he sentenced to, guys?” Hickey asks the crew when the cameras stop rolling. She looks around the room, waiting for a reply. Walls of little red lights twinkle behind her, and the freshly shined stage gleams beneath her feet. A crew member tells her that a sentence hasn’t been announced yet, but that Twain’s stalker has already pleaded guilty. “We should get a security expert to discuss what celebrities think is a big deal and what’s not,” she suggests.

“Five, four, three….”

“Demi Moore steps out alone!” Hickey says to the camera, her voice full of drama and intrigue.

•••

This is the heart of the beast, the backstage pass, the sparkle in our eye. The entertainment news show is our glimpse into the world of celebrity, from the glamourous lifestyles to the scandalous downfalls. The Canadian entertainment news show genre is still young, just a decade old this year: CTV’s etalk launched in 2002, and ET Canada (wide-eyed little sister to the American Entertainment Tonight) was created in 2005. Both have achieved varying levels of success, though, tapping into our seemingly insatiable appetite for celebrity gossip: etalkcurrently averages 601,000 viewers, with an audience of 1.9 million combined over CTV‘s three broadcasts per night; it can draw close to one million for special coverage, like the day after the Oscars. By comparison, CBC‘s The National averages 505,000 viewers per night. ET Canadawould not reveal the viewership for its main evening broadcast; it would only tell me that each episode gets about 500,000 viewers total, a statistic that combines the show’s five airings on three networks.

Until last September, that popularity was helped by the shows (along with Canadian dramas and documentaries) being designated as priority programming by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. That meant broadcasters were required to air them during prime time. For the entertainment shows, it also meant they had to follow Canadian content regulations, devoting at least two-thirds of each episode to covering Canadian entertainment news. The CRTC eliminated priority programming altogether (a decision made in 2010 but implemented as of September 1, 2011), replacing it with strict spending requirements (a certain percentage of each broadcaster’s revenue has to be spent on Canadian shows). However, the CRTC did not implement a new Canadian content regulation for entertainment news shows, meaning nothing forces them to concentrate on Canada.

“The initial idea of allowing shows such as etalk and ET Canada to qualify as Canadian content was the notion that they could be used to promote a Canadian star system and help build audiences for other Canadian content,” says Globe and Mail cultural affairs writer Kate Taylor. Now these shows presumably feel they have accomplished that goal and can move past it—and the CRTC seems to agree.

“What [these shows and their broadcasters have] done now is say, I guess, ‘We don’t need that anymore. Give us the flexibility to do what’s best for us,'” says Phyllis Yaffe, former CEO of Alliance Atlantis. “And I’m sure somebody said, ‘People know our stars more, so a regulation about what percentage should be Canadians is kind of overkill.'”

“In the last 10 years, the world’s changed, with more people watching broadcasting on the internet and with on-demand programming, so the schedule and linear service is becoming less relevant, less important,” says Peter Foster, director general of television policy and applications at the CRTC. “The thinking was that imposing exhibition requirements for specific programming is becoming less and less effective in terms of Canadian programs.”

In regards to Canadian entertainment news shows, and the fact that there are now no regulations surrounding the amount of Canadian news they cover, Foster says it comes down to the fact that such a rule was very hard to administer. “I think with the e-magazine shows, that was an attempt to work out in English Canada—not Quebec, it’s fine there—the need to try to create a star system,” he says. “I think the jury is out on whether or not that was happening. Also, [the rule that] two-thirds of each episode had to be covering Canadian issues really was a very difficult provision to enforce.” So the CRTC no longer does.

•••

Back in the studio it’s 11:30 and Hickey’s co-host, Rick Campanelli, walks in. Short and fit, with brown hair and a big, white smile, Campanelli heads to centre stage to take his turn filming the day’s links. His black dress shoes are shiny, his pinstriped suit well-fitted. He pauses after filming a teaser for a clip of Canadian actress Sandra Oh being inducted into Canada’s Walk of Fame.

“She’s a sweetheart, that Sandra,” Campanelli says to the crew when the cameras are off. “She’s so nice.” After a few more links, they film Campanelli doing some behind-the-scenes stuff; floor director Mark Bullock comes on stage and pretends to be showing Campanelli some important notes. (Picture the credits rolling overtop.) “Why do we have to smile all the time?” Campanelli jokes as they break for lunch. Everybody laughs. The lights go down.

•••

The entertainment news show has evolved since the original American Entertainment Tonight—the first of its kind—came on the air in 1981 and host Mary Hart dazzled her way across our TV screens. Robert Thompson, professor of television and popular culture at Syracuse University in New York, remembers when Entertainment Tonight was more of a trade show than a gossip one.

“The show started out as if a news broadcast had an entertainment section, and they lifted that out and made a show out of it,” Thompson says. “They used to report on which directors signed to which studios and how various shoots were going. It was some gossip but also a lot of reporting on the entertainment industry. Now that balance has shifted in favour of the gossip: pictures of a celebrity’s baby, talk about Demi’s divorce.”

The internet, undoubtedly, has dramatically changed these shows along with the rest of the media. It has affected what gets reported, how it gets reported, and how we consume it. Canadians now have more access to the celebrities these shows have been trying to highlight; almost every star these days has a Twitter account, a Facebook page, a Tumblr, or all three. And this, in turn, means the pressure is off ET Canada and etalk to make Canadian celebrities seen and heard.

•••

Even when the cameras are off, Campanelli is on; always peppy, always excited to be here. He’s aware that ET Canada is not the most hard-hitting show, but still thinks it is journalism. “We’re not saving lives, that’s for sure,” he says. “It’s obviously entertainment. It should be playful; it should be fun. It’s not a serious type of program like The National or stuff like that, but it still is journalism. We’re still reporting on things.”

Of course, there are those who disagree; Taylor thinks these shows are “not a form of news but a form of marketing,” and Shinan Govani, social columnist for the National Post, sees a lot of Hollywood-driven news “as just comedy. It’s like having a Snickers bar, and I don’t attach any more or less importance or outrage about it.”

But entertainment news shows do have journalistic qualities, according to Dave Itzkoff, a culture reporter for The New York Times. “The basics of journalism are to go out, talk to ideally first-hand sources, come back and tell me a story,” Itzkoff says. “The nature of the stories is different from what’s on the front page of The New York Times on any given day, but the mechanism is presumably the same.”

But the question remains: Is this CRTC change good for these shows, and moreover, good for the Canadian entertainment news cycle? There is no arguing that it grants the shows more freedom. “It gives us licence to give stories what they deserve. Instead of planning everything based on Canadian content, we plan it on what’s best for the show—what do the viewers want to see?” says ET Canada senior executive producer Tamara Simoneau.Still, many are upset by the change, including host Campanelli. “We started our show to build up the Canadian star system and I love that, whether it’s discovering Canadian talent or giving props to Canadians out there who are in music or acting or sports or whatever it is,” he says. “The fact that it’s no longer a requirement is kind of sad. I’d much rather promote or talk about Canadians—and the fact that we’re proud of Canadians—than talk about or promote upcoming Americans.”

Globe television critic John Doyle agrees. “I would be very wary of any outright diminishment of Canadian content regulations as they apply to Canadian commercial broadcasters,” he says. “They don’t have a history of being proactive in terms of paying attention to the Canadian culture. It is only when they are obliged to by regulations that many of them do so.”

And beyond looking at whether these shows are doing their job, we have to look at whether the CRTC has done what it is supposed to do. “I think it’s always fair for us to ask, as a society, what is [the CRTC] doing for us and are they doing enough?” Taylor says. “Because make no mistake about it, without the CRTC, without regulations, there would be no such thing as Canadian broadcasting. If you had an open market in North America, you’d sit and watch only American television.”

Despite the change, both ET Canada and etalk claim that Canadian entertainment news is still important to them and that they will carry on covering it.

“Etalk continues to act as if we are required to produce two-thirds Canadian [news], although not as stringently,” says executive producer Morley Nirenberg in an email. “The formula has definitely helped us remain number one. Why break it?”

I taped episodes of etalk and ET Canada on January 12, 2012 (a date chosen at random), and timed the Canadian coverage of both shows to see if this was true. Neither seemed to carry more than six minutes of Canadian entertainment news—a number far less than the minimum of approximately 14 minutes that would have been mandated under the old regulations.

Still, some people think the overall, long-term shift in these shows will not be that drastic. “Once we got over the hump of, ‘if it’s Canadian it must be bad’—and that used to be true—I think we could celebrate our stars,” says Toronto Star TV columnist Rob Salem. “I’m willing to bet that the mix [of Canadian and American news on ET Canada and etalk] will not change that much. The bottom line is we are not embarrassed to embrace our own talent; if anything, we’re quite proud of it.”

•••

Back in the studio after lunch, Hickey and Campanelli film together. Perched behind a shiny desk, they trade lines and interact playfully with each other. They read the top headlines one last time, film their teasers for the next day’s show, and sign off. Around 2:40 p.m., reporterRosey Edeh comes in to film her links, including a Kim Kardashian spotting in New York, and the kick-off of Toronto Fashion Week. In another 20 minutes the filming is done, and the editing crew begins to piece the show together. Links are added to their corresponding clips, voice-overs are inserted, and the sparkly ribbons are tied around the glossy package.

By 5:30 p.m. the show is sent to its central feed in Calgary and broadcast across the country: 21-and-a-half minutes of big smiles and shiny hair and expensive clothing and heartbreaking divorces—and access to it all.

Photographs courtesy of CTV/Global Television.

Sara Harowitz was the Editor of the Summer 2012 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.