To Report and Protect

With the assistance of a confidential source, Daniel Leblanc helped uncover the sponsorship scandal that rocked the Liberal government. Now the reporter is being asked to name names Katherine Laidlaw looks at the Supreme Court case that could reshape investigative journalism in Canada

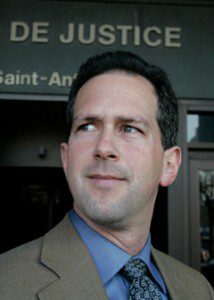

Globe and Mail reporter Daniel Leblanc arrives at court in Montreal, Quebec, on November 5, 2008

photo by: Ian Barrett (courtesy of The Globe and Mail)

“While he likes the occasional brown envelope, he is also open to anonymous emails.” That’s the cheeky one-liner Daniel Leblanc delivers at the end of his Globe and Mailonline bio. An Ottawa-based reporter since 1998, Leblanc has been fighting the absence of source protection in this country for four years. Next week, he’ll sit in the Supreme Court of Canada, but he won’t be covering a hearing—he’ll be watching his own. Leblanc could face a contempt of court charge for his role in the sponsorship scandal: refusing to reveal the identity of a crucial source in a story so influential it helped destroy the Liberal government’s chances of re-election in 2006.

The source’s name is Ma Chouette, Leblanc’s “sweetie” to Woodward and Bernstein’s “Deep Throat.” Leblanc promised he’d never reveal her identity in exchange for her assistance, the kind of deal many investigative reporters offer, and he’d rather go to jail than break his vow. “This was a source who blew the whistle—in the public interest—on massive fraud, so I’m willing to go wherever it needs to go,” Leblanc told CBC News in March. The Supreme Court, which will hear the case on October 21, can order Leblanc to reveal Ma Chouette‘s identity. If he refuses, his challenger, ad firm Groupe Polygone, can press charges, which could lead to a contempt of court charge that could mean a fine, or even jail time.

Leblanc’s not the first journalist to promise a source confidentiality, but his case highlights the absence of a shield law to protect confidential sources. Investigative journalists say they need to be able to make these promises to their sources or the whistleblowers won’t talk, and many stories will go untold. The court’s decision could be a step closer to protection for journalists and sources—or not: a ruling against the paper and its reporter threatens to perpetuate a culture of silence reporters say already exists.

“Wherever it needs to go” has been tested before. Former New York Times reporter Judith Miller is the oft-cited example of a journalist doing time—85 days—after refusing to break a promise of confidentiality. But in the United States, the laws are different. Some states have shield laws, giving reporters absolute privilege when it comes to protecting their sources. A federal shield law is before Congress, although the Obama administration has told the Times it doesn’t support the bill. No such laws exist in Canada for journalists. Leblanc’s case is one of several that will likely be ruled on this year and will shape the future of source protection.

Another case involves Andrew McIntosh. While he was a National Post reporter, he broke the Shawinigate scandal in 2001. As part of his investigation, he received a confidential document the RCMP suspects is a forgery and wants access to. McIntosh’s hearing has passed, and the Court will decide if he must reveal his source. And, in 2004, a Superior Court judge charged Hamilton Spectator reporter Ken Peters with contempt of court and fined him $31,600 when he refused to reveal a source during testimony. The source came forward and testified in the case, but Peters was still fined. The Ontario Court of Appeal later struck down the ruling.

Groupe Polygone is embroiled in its own lawsuit with the federal government, which is trying to recoup $35 million of the money allegedly paid to the company during the sponsorship scandal the Globe uncovered nine years ago. Last spring, Justice Jean-François de Grandpré of the Quebec Superior Court ordered Leblanc to answer questions about his source for Groupe Polygone. The Globe filed an appeal, which the Quebec Court of Appeal dismissed. The paper then appealed to the Supreme Court, which has agreed to hear the case.

William Brock, a lawyer for the Globe, argues that a ruling against the paper would set a dangerous precedent, where journalists would offer fewer promises of confidentiality—contingent, perhaps, on a trip to a courtroom. “The burning question is, will the next Ma Chouette step forward?”

Investigative reporters argue they need the freedom to offer confidentiality to sources in order to best serve the public. “Many times, it’s the only way you can get information in the public interest,” says Harvey Cashore, producer of the investigative content unit at CBC News. “The reality is there are certain people who cannot talk publicly, but can privately.” This is not to say reporters should be free to report anything they want. The onus, he maintains, is on journalists to check out information provided by any source, confidential or not. “It’s too simple to say we should reveal our sources if they lie to us,” Cashore says. “It allows us to get off the hook too easily for not doing our homework.”

Part of the struggle to win source protection is convincing the public it matters. Bruce Ryder, an Osgoode Hall law professor and constitutional law expert, thinks there is a lack of public awareness in cases like these, because it’s hard for readers to care about information they’ll never learn. “The effects of the failure of the law to provide strong confidentiality to journalists’ sources are almost not visible,” he says. “The effects are what we don’t come to find out.” Cashore adds that it’s challenging to convince the public this is an issue they should care about. “I think part of it has to do with how we view our democracy,” he says. “We don’t really trust the media, therefore we don’t want to give them that protection.”

Public trust aside, some argue a weak stance on source protection is an infringement of rights. For a country not to have shield laws is at odds with the freedom of expression right in the Charter, says Dean Jobb, associate professor of journalism at the University of King’s College in Halifax. “From a citizen’s point of view, it’s pretty offensive to see one of the key guys who exposed this now on the firing line. He was doing his job. Somebody took a hell of a risk to help him. It’s not easy to get people to take risks.”

The Supreme Court sped up Leblanc’s case and has not yet ruled on McIntosh’s. That’s led some to believe the judges want to establish a framework for source protection—a relief to investigative journalists such as Cashore, who says, “We need to create an environment where people will talk.”

Katherine Laidlaw was the Editor for the Spring 2010 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.