Are letters to the editor still worth reading?

Although readers once cherished getting their words published in their favourite newspaper, the page’s migration online means more content and less substance

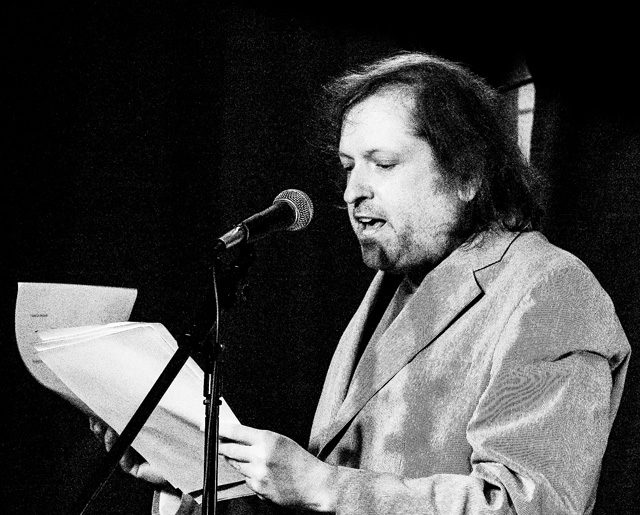

When Bob Dylan brought his Christian gospel tour to Toronto’s Massey Hall in 1980, he didn’t play his popular songs from before 1979. The ensuing controversy carried over to newspapers, where Toronto Sun reader Douglas Greenwood wrote a letter to the editor, reminding people of Dylan’s Jewish heritage. Some of Greenwood’s comments, such as, “If he is not a Christian, let’s not put too much significance in his singing about Jesus Christ,” upset 19-year-old Bobby Anderson—a poet and avid Dylan fan—who’d picked up a copy of the Sun issue at his local smoke shop.

Anderson grabbed a pencil and sheet of paper and wrote a response to Greenwood. He agonized over the grammar and syntax because he wanted to sound intelligent, not like some cultish Dylan-worshipper. He was thrilled when his letter was published. “I had entered into the adult world of public discourse,” he says today. Anderson still has the clipping of his letter beneath its own bolded headline: “Bob Dylan would not be amused.”

While letters to the editor used to be revered in newspapers and a thrill for writers who made the cut, over the years, word counts have shrunk and writing quality has diminished in the name of speed. While many mourn what’s been lost, some editors see today’s letters pages as more accessible and more democratic.

In 1980, Bobby Anderson wrote a letter to the editor defending Bob Dylan, who had just come to Massey Hall in Toronto to perform (PHOTO: COURTESY OF RALPH KOLEWE)

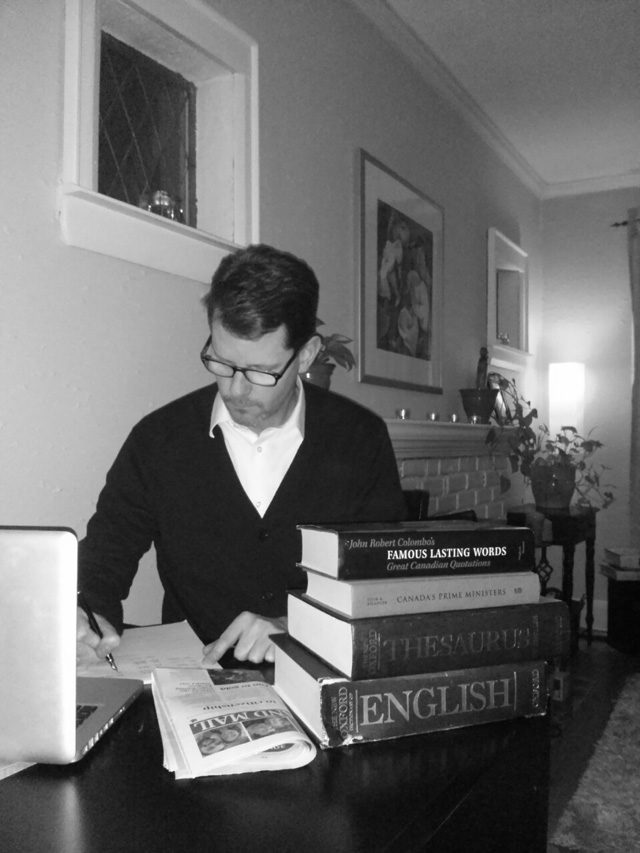

Letters to the editor have been around since the dawn of newspapers, but over the years, they’ve lost their cultural cachet. William Thorsell, former editor-in-chief of The Globe and Mail, points out that having a letter published around 1990 gave you special access to a large population and, thus, coveted influence. Today, he adds, letters are buried in so many competing viral voices. J.D.M. Stewart, a regular letter-writer to the Globe, says his new rivals are less dedicated to the cause: “Anybody can write a letter to the editor now, because in the old days, it took a little bit of effort.” Before, people with something to say needed to find paper and a stamp and walk to the mailbox. Now, they type and click send.

Aside from the transformation engendered by technology, the most obvious change to letters to the editor over the last two decades is length. Fifteen years ago, the Globe asked for 400 words or fewer; 10 years ago, it wanted 250. Stewart, who keeps a scrapbook of 200 of his letters, says he must now keep his word count to 150.

But that hasn’t dampened readers’ interest in sharing personal opinion. Robert Wright, who was letters editor at the Toronto Star from 1985 to 1987 and returned to the position five years ago, says he used to get about 100 mailed letters in a week. Now, he receives between 200 to 400 emails a day.

Yet the immediacy has increased knee-jerk responses. “In some ways, because [email] makes it easier, it cheapens some of them,” says Paul Russell, former letters editor at the National Post. Russell, who was laid off in January 2013 along with other Postmedia staff, says there were more rants out of the 150 missives he would receive each day. Clever and creative writing has also suffered: “Not that it’s disappeared,” says Wright, “but you have fewer colourful letter-writers.” About half are mindless tirades, spam or hoaxes.

Not everyone agrees that the days of typewriters and handwritten letters were better, though. “A lot of crap was sent in to newspapers then as well,” says Andrew Phillips, editorial page editor at the Star. Many letters were illegible. And with fewer to choose from, the pool of discourse was diminished. Now, a diverse array of opinions floods email inboxes.

J.D.M. Stewart is a regular letter-writer to The Globe and Mail and keeps a scrapbook of his letters (PHOTO: COURTESY OF MADELEINE STEWART)

Not all good letters can fit in a paper, but websites give a home to letters that would otherwise have been trashed. Besides the six to 10 letters that make it to the Star’s print page, another 10 to 20 go on the online opinion page. And the word constraints in the hard copy encourage more focus. “Letter writing is a bit of an arcane institution, but now you get more learned, factual-based opinion,” Wright says. “Shorter letters have also pushed readers to articulate their opinions.”

Meanwhile, online culture has led to a more relaxed tone. Tim Currie, assistant professor of journalism at the University of King’s College, says, “Today, the language is much more casual. And that’s born of social media.” This language—more approachable and less stuffy than handwritten letters of the past—is more inviting for readers. As columnist Robert Fulford recently wrote in the Post, not only are email letters “more detailed, better argued and in general more skillful,” but the writing is also more fluent—“the first step to engagement.”

Today, engagement extends to roving the Internet for public discourse, rather than going straight to the letters page to gauge discussion on hot topics. Even though more letters are available online, according to Currie, it’s important that they appear next to the articles they refer to, for reader interaction. Some may be hyperlinked to a piece, but they’re still on a separate page. Instead, comments—some more moderated than others—are more likely to catch the eye of readers.

Still, in an age when news organizations have yet to balance what the Star’s public editor, Kathy English, describes as “the demand for unfettered expression with a desire to foster civil discourse,” the letters page, no matter what medium, still offers a place for informed discussion. More opinions, carefully curated by editors, result in a liberated and nuanced debate. But with Russell’s departure, the Post no longer has a dedicated letters editor—the work is shared among people in the comments section who have their own responsibilities.

Other news outlets haven’t abandoned this position. Sifting through letters about the death of former Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon, Wright tries to narrow down different opinions for print to reflect the readership; the remainder will be posted online. Sometimes, when he’s reading the Star over the weekend, he can spot the influx ahead of time. Stories about education or Mayor Rob Ford usually entice people to express their opinions, he says, laughing. “I can go, ‘Oh yeah, that’s going to be a big one.’”

Related Posts

Mental health: why journalists don’t get help in the workplace

Mental health: why journalists don’t get help in the workplace That Was Then, This Is Now: Jian Ghomeshi

That Was Then, This Is Now: Jian Ghomeshi A novel approach

A novel approach Campus clampdown: student governments bully the papers that cover them

Campus clampdown: student governments bully the papers that cover them Sally Armstrong: the editor who changed women’s magazines

Sally Armstrong: the editor who changed women’s magazines ‘The company does not love you’: the editorial cartoon after Roy Peterson

‘The company does not love you’: the editorial cartoon after Roy Peterson

Rebecca Melnyk was the Head of Research for the Spring 2014 issue of Ryerson Review of Journalism.