What’s in it for us, though?

There's no shortage of Canadian media coverage of United States presidential candidates Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, John McCain and even Mike Huckabee. And why not—some of the horses are running neck and neck. But left in the dust is what each of these candidates might actually mean for Canada

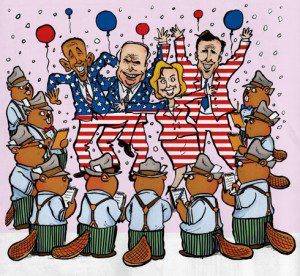

Illustration by James Grasdal

The Globe and Mail’s Washington bureau correspondent John Ibbitson vividly remembers the first time he saw U.S. Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama speak in person. On an early December 2007 day in Columbia, S.C., he was standing in a press pool 12 to 15 metres from the stage, listening intently. Obama spoke and paced the stage for 40 minutes in front of a largely black audience. He recalls the power of Obama’s speech affecting him emotionally, poking holes in his reporter’s detached objectivity. “I was mesmerized,” he says. “I found it very hard to be a reporter that afternoon.”

More like a revival meeting than political rally, Obama owned the ecstatic crowd. “I just thought,” Ibbitison says, “what a compelling presence this man is.”

Ibbitson is just one of a horde of reporters covering the extraordinary 2008 United States primaries. Horde might be an understatement. Christopher Hayes, Washington editor of The Nation, is blunt about the numbers. “This is the most covered election, I would dare say, in the history of humans on the planet.”

As a result, American media coverage of the primaries is laced with pollsters, pundits and prognosticators. Networks and newspaper websites obsess over the horse race and dedicate large amounts of coverage to it in the belief that viewers want the play-by-play commentary. But this play-by-play, Super Bowl-like coverage — Obama’s race, Huckabee’s “aw shucks” folksiness, even Hillary’s infamous quaver — benches the real substance of any political campaign: issues. In the whirlwind of coverage surrounding the candidates themselves, the issues simply aren’t getting enough play — and Canadian media are following suit. Outlets such as the Star, The Globe and Mail and CBC provide vigorous, updated campaign coverage on a daily basis, but it’s questionable whether the coverage is adequately informing Canadians of what’s important to them.

Ibbitson says he’s confident that the Globe covers the U.S. primary issues important to its readers. He isn’t trying to scoop The New York Times, he says, so he has time to write about debates over issues such as health care and immigration. And, as a Canadian columnist, he tries to avoid being obsessively comparative. “I’m trying to treat the race as a race and the country as a country,” he says, “not just as a foil for Canadian issues.”

But as the horse race continues, and as delegates consider the leadership qualities of each potential president, Ibbitson believes these concerns start to slide to the back of people’s minds. And Canadians, he says, inevitably are attracted to the same criteria used by delegates: “Whom do I trust? Whom do I think is closest to my values and concerns? Whom do I believe that, once in the White House, can handle an unexpected emergency?” And finally, “Who has the knowledge and experience?”

When that happens, Ibbitson says, the nitty-gritty of candidates’ positions becomes less important. “The issues of trust, of confidence, of reform and of leadership,” he says, “are far more important than whose health care plan is going to be more inclusive.” The political narrative of the Democratic race is intensely compelling, he says, citing Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama as being “two terrific stories” and the battle for the Democratic nomination as “one terrific story.”

Toronto Star Washington bureau chief Tim Harper began his trek on January 1 in the snowy state of Iowa. Then he hopped east to New Hampshire on the fifth, ending up in South Carolina 11 days later. Once there, he stayed put for 12 days straight. Almost two weeks after South Carolina Republicans had chosen John McCain, Harper’s trip ended with a night camped out in front of the television in his Charleston, S.C. hotel room, waiting to find out the Democratic Party’s choice for the state.

Harper is responsible for suggesting and then deciding what he thinks should be reported and why, and when and how it should be covered. Working with foreign editor Martin Regg Cohn, Harper maps out his route and coordinates who flies in to help him on the trail. Covering the races is certainly harder this time around, and requires more reporters on the ground than previous elections. “There are two to juggle,” Harper says. “In 2004, there was only the Democratic race.”

Harper says he’s made a point of going beyond the standard horse race coverage. He tries to explain to readers the specific demographics and political landscape of the state where each contest is taking place. Canadian foreign correspondents might as well be as foreign to Americans as Albanians, yet he’s had almost unlimited access to voters, and found many Americans eagerly wanting to share their opinions. At a rally in Derry, N.H., for example, he spoke with people who’d lined up for two hours to see Obama, many carrying babies. Some had driven all the way from Massachusetts. At the same rally, he saw teenage girls squished against barricades, cameras in hands, full of anticipation, too young to vote, but waiting for Obama.

Harper also says he’s tried to make the race relevant to Canadians. He’s written extensively on the candidates’ differing views of the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which are important to Canadians. He’s written stories about Clinton’s health plan proposal and compared her stance to Obama’s policies on this topic. He’s also written about the Democrats’ general opposition to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), as well as the Republicans’ obsession with border security. “I’ve tried to write about that,” he says, “because Canadians can get side-swiped by anything that happens on the immigration front.”

But, Harper admits, he hasn’t explicitly pointed out to his readers that for all their left-leaning appearances, Obama and Clinton are more conservative than Canadian left-wing politicians. For one, both are against gay marriage. “It’s pretty well-known by anybody paying attention that what’s considered left wing in the U.S. is considered moderate in Canada,” he says. “And that the Republican Party,” he adds, “is much more to the right and conservative than Canadian conservatives.”

Not all commentators think the upcoming election is of the greatest urgency to Canadians. “I don’t think it’s important,” says Chicago native Clifford Orwin, a Globe contributor and professor of political philosophy at the University of Toronto. “I doubt the fundamental character of Canadian-American relations is at stake.”

Orwin does allow that the world is in a critical state and that Canadians are experiencing it through their participation in the NATO mission in Afghanistan. In terms of coverage of where candidates stand on Afghanistan and other issues Canadians consider important, Orwin blames the candidates themselves rather than the media. He insists that candidates have not focused on policy issues from the start and instead concentrated on issues surrounding the candidates personally, which has justly been reflected in the media. While Obama is the first black contender with a serious chance for the presidency since Jesse Jackson, and Clinton is the first woman, Orwin is concerned with the unclear policy implications of these obvious factors. “Since both candidates are about change,” he says, “you might think there would be discussion in regards to the kind of changes they want.”

Along with political issues, the media could also be accused of ignoring the candidates who are not Clinton, Obama, McCain and Mitt Romney. Candidates such as John Edwards, whom Orwin describes as an underdog from the beginning, couldn’t get himself to be taken seriously. He describes the vicious cycle Edwards was caught in: “If you don’t do well, the press doesn’t pay attention to you,” he says. “And you do less well, and the press pays less attention to you.” Harper agrees with Orwin, offering this image: “Edwards was like a candle trying to find room between two spotlights.”

Orwin’s comment certainly rings true for Rudolph Giuliani as well. If Canadians wonder why they didn’t hear more from “America’s Mayor” before he dropped out, it’s because he fell off the media radar right from the start. Harper says, “It’s hard to write about a guy who isn’t campaigning in Iowa, New Hampshire or Michigan.”

While Orwin hoped for more coverage of the issues in Canadian media on Super Tuesday, the horse race coverage won out again. And that’s understandable to some degree — it is the most competitive political horse race for the Democrats in decades.

For the first time since Super Tuesday, at the Elephant & Castle Pub and Restaurant on King Street in Toronto, there’s a handwritten sign on the Simcoe Street entrance that reads “Democratic Primary Voting Back Room!” Tonight, February 11, expatriate Americans living in Toronto can vote in the primary contest and send delegates to the Democratic national convention with the Democrats Abroad organization.

Robert Bell, a committeeman, is busy handing out forms to expatriates so they can register. He bustles back and forth in the tiny room answering questions. Adrienne Jones, chair of Democrats Abroad Canada, moves around the room making sure everyone is taken care of. “We were packed last Tuesday,” she says. “There were hundreds of people here.” Even Mayor David Miller. Tonight, Mary Ellen Hebb and her husband drove in from London to vote because she missed the opportunity last week in her hometown. While Jones agrees Canadians are interested, she says, “I don’t think the Canadian media has covered the issues.”

She doesn’t blame the journalists, though, because she says, “There’s not enough time in radio and TV.” The coverage will change after the nomination tussle is over, she thinks, “because the disparities between the candidates will be bigger.” That’s when, both she and Bell agree, the Democratic candidate and party will be more receptive to Canadian issues and concerns such as the environment and universal health care.

by Nina Boccia

Nina Boccia was the Heads of Research for the Spring 2008 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.