April 16, 2013

Davida Ander

canada , comments , journalism , media

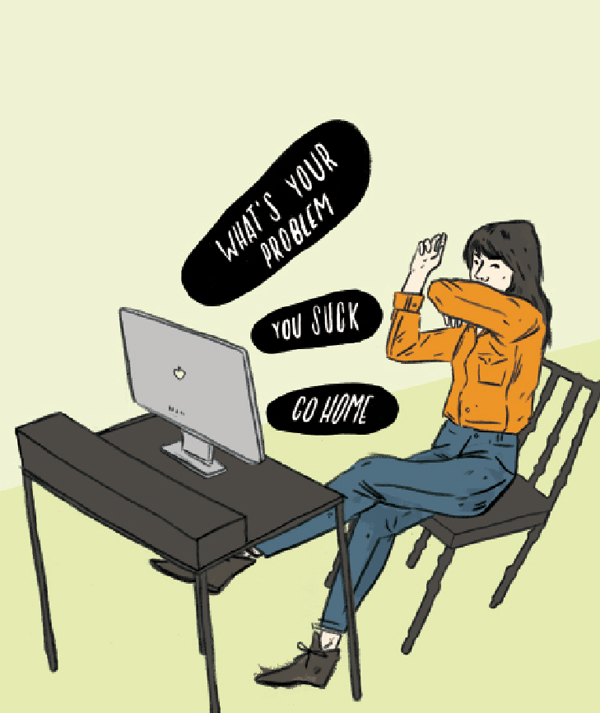

When readers attack

Why are online comments so extremely loud and incredibly verbose, and what can be done about it?

By Davida Ander

By Davida Ander

“What’s your problem?”

“Isn’t it obvious? He’s an unemployed welfare bum.”

“Grow up.”

“Once you are done you may fornicate yourself.”

“You just antagonize people to get people to react, dude. It’s what you do! You have serious issues!”

“I win every time due to your lack of brains, slightly amusing on occasion but bore quickly of you, til next time I’m bored, bye bye schmuck….”

“Bye bye, coward.”

“This comment has violated our Terms and Conditions, and has been removed.”

These are just a handful of the comments immortalized for posterity on a

November 2012 story on

The Globe and Mail‘s website. That story, ironically, was about changes to the newspaper’s commenting policy intended to make discussions more civil and substantive. It was titled “What to Do When Online Comments Get Out of Hand.”

For most people who avoid wading into the swamp of insulting idiocy and irrelevance that characterizes most newspaper comment sections on the web, the question is more whether comments have ever been in hand. They seem more like the graffiti of the internet: uninformed, semi-literate scribblings on a bathroom stall.

“We have a joke,” says Jonathan Kay, editor of the National Post‘s comment pages. “If you write an article about libertarian economic ideology, by the fifth comment there’s a guy arguing about whether Ayn Rand is a lesbian.” He’s fed up with some of the commentators he encounters, saying that they can often be angry and embittered.

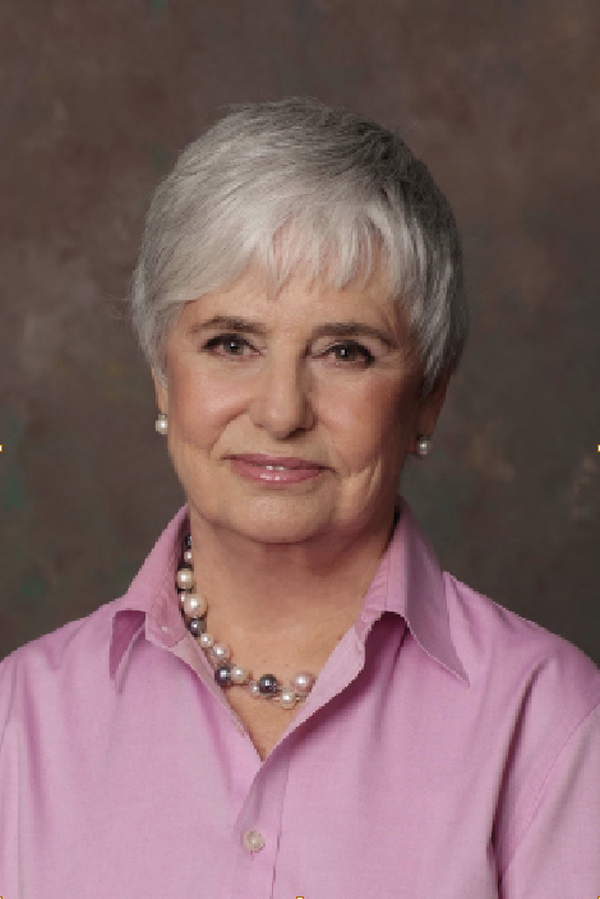

Bitter and angry spew has led journalists like Barbara Kay, also of the Post and Jonathan’s mother, to stay far away from the comments section, and to converse with readers by email instead. “The comments section unfortunately sometimes attracts the bottom feeders of society. I never engage with people who write in the comments section after the column. People with a real argument to make, respectfully, write to me directly,” she says.

For the large, silent majority of readers turned off by comments sections, the solution is simple: stop reading them. But for journalists, who are frequently themselves the subjects of discussion, and who are increasingly being pressured to moderate and participate in online discussions, ignoring the problem just isn’t an option anymore.

simple: stop reading them. But for journalists, who are frequently themselves the subjects of discussion, and who are increasingly being pressured to moderate and participate in online discussions, ignoring the problem just isn’t an option anymore.

Nor should it be. Canadian news sites need to become more comment-conscious and replace vague suggestions for comment response with positive examples, clear policies, and how-to instructions. Frustrating as comments sections can be, useful contributions should be welcomed—and deserve to be answered.

There are positive examples out there. For Kim Bolan, responding to reader comments on her Vancouver Sun crime-beat blog means getting access to exclusive information from some of her gang-involved readers. “Sometimes it’s a little tidbit of information, because people will post, for example, the name of a murder victim long before the police are prepared to give that information out publicly. So I get it and I have to, of course, confirm it, but I get a leg up, in essence, because I’m on this blog and communicate with people,” she says. And Bolan’s work has paid off. She says her blog averages 250,000 to 300,000 readers each month, one of the highest numbers in the Postmedia chain for a blog. Bolan’s participation in her blog’s comments threads has not just improved the tone and quality of the comments; it’s paid dividends for her reporting, as well as the size of her audience.

But when it comes to journalist-reader interactions in the comments sections of Canadian media, Bolan is an exception. While newsrooms encourage journalists to dip their toes into the comments sections, they’re rarely instructing them on the practical level: when to respond, and how.

At the Toronto Star, editors are working on a new comments strategy. The current guidelines say journalists “may respond” to online reader comments, but debating any issues is off limits. Any reader concerns or complaints should not be addressed by the journalist; instead, they should be sent to the public editor for investigation. “We’re starting to have a conversation around just exactly what is the comment section for,” digital editor John Ferri says. “Should there be a conversation in it? Should we consider it content? All those questions are being discussed.”

At The Gazette in Montreal, editors are developing the comments strategy and moving in the direction of encouraging reporter response. “The strategy for various platforms is kind of being unrolled right now,” Thomas Ledwell, the social engagement editor, says. “We want to proceed with caution.”

The

Globe has more lenient

community guidelines, but they are still speckled with resistance. Writers are encouraged to engage with reasonable reader comments. “Given the time constraints of their jobs, however, they may not be able to do so,” the guidelines say. Stephen Northfield, until February the deputy managing editor of digital, says, “It’s, broadly speaking, encouraged at an institutional level, but it’s left up to the journalists themselves to decide on their own how much time they want to spend on it and how important it is.”

The CBC has been among the leaders in trying to effectively harness a rowdy commentariat. CBC contracts out its comment moderation to a Winnipeg-based company called ICUC Moderation Services Inc., which screens more than 300,000 comments per month on CBC stories. Last year, the broadcaster’s community team initiated a one-month pilot program, during which the ICUC team was asked to flag any conversations that could benefit from reporter interaction. Then the community team forwarded these comments to the appropriate department for response. The trial had limited success because ICUC moderators were only able to highlight a handful of comments on a daily basis, and with great difficulty. The CBC community team says it’s analyzing the results of the trial and continues to experiment with the comments section.

Several news organizations outside of Canada are a few steps ahead. At

The Guardian, instructions to reporters diving into the comments are grounded and specific.

Best practice guidelines ask journalists to reward clever reader contributions by responding, to include additional links when necessary, and to reveal personal interests if they please. “Participate in conversations about our content, and take responsibility for the conversations you start,” they recommend.

Jon DeNunzio,

The Washington Post‘s interactivity and community editor until last year, similarly recruited staff to post in the comments, because he found it improves the tone of the threads, and the journalism.

“Readers pose legitimate questions and participate in interesting debates in the comments, and those threads offer reporters, bloggers, columnists, and editors an opportunity to elaborate on their work and the ideas behind it,” he wrote in an October 2011 Q&A article titled

“Why Don’t More Post Reporters Respond to Reader Comments?”Washington Post journalist Donna St. George found that participating herself—and even more effective, deputizing other qualified commenters—improved the tenor of discussion and made the experience less painful. When a

story she wrote on the high suspension rate for African-American students in Washington schools quickly amassed more than 2,000 comments, St. George decided she had to respond to reader questions and critiques. She addressed commenters by name, added follow-up statistics, and introduced another facilitator to the fast-paced discussion: Dan Losen, a researcher she had quoted in her story. St. George later reflected on the experience in an article published in January 2012 in the

Post, writing that the discussion set-up could be used as a model for the future, with exchanges between readers and those behind the scenes enriching the conversation. “That way, our readers [could] gain access to people with whom they don’t ordinarily get to exchange ideas. It might deepen the experience of reading and commenting,” she wrote.

Human interaction may be the most effective means of taming comments threads, but for the time-starved journalists who populate modern newsrooms, some automation is necessary too. News organizations have begun tidying up by allowing readers to rate comments based on their perceived quality. Readers are realizing that not all comments are valued equally, and that more and more, quality is trumping quantity.

An improved commenting system may be one of the reasons why comments on

The Huffington Post increased from 54 million in 2011 to 70 million by October 2012. Foursquare-esque badges were added to the comments in April 2010 to identify readers who had commented, reported abuse frequently, or networked stories with social media. At

The Huffington Post Canada, comments increased from over 40,000 in the first two months of the site launching in May 2011 to close to 25,000 comments per week as of February 2013. All these steps reward good commenter behaviour, and download some of the workload of monitoring conversations onto the users, saving reporters and editors time.

On the Globe’s website, for instance, over 6,000 comments are posted each day, far beyond the capacity of a small group of “community editors” to police on their own. These long streams are smoothly organized with a user rating system that subtracts the number of thumbs-down from the number of thumbs-up. Comments with the highest score are placed at the top, and readers can use a drop-down menu to view comments chronologically.

Before a journalist dives into the comments pool, it’s important to ascertain a purpose. “It’s not a matter of becoming part of a debate. It really is a matter of addressing concerns, filling holes in information, updating people if it is a breaking-news story, or that sort of thing,” Ledwell from The Gazettesays.

Journalists do not always get positive responses when comments diving. The way they act, the subjects being discussed, the platform for the interaction, and the commenter’s underlying purpose are all factors that can determine a civil—or uncivil—outcome. According to Whitney Phillips, a lecturer at New York University who examines the culture of “trolling,” it’s impossible to make general claims that every time a journalist interacts with readers in comments, the impact will be positive. When it comes to trolls, any attention can serve as a reinforcer. “Knowing that someone is watching only incentivizes bad behavior…the internet version of the aphorism, ‘If a tree falls in the woods and no one hears it, does it make a sound?’ updated to ask, ‘If an asshole spews his bile online and no one sees him do it, did he ever post at all?’” Phillips says. To avoid stirring up evil, she suggests ignoring ad hominem attacks that say, “You are a bad person,” but to pay attention to those that say, “Your argument is bad.”

As long as the public is involved, many comment sections will continue to be a zoo. According to the 2011 book

Participatory Journalism: Guarding Open Gates at Online Newspapers, newspapers published between 5 to 50 percent of the letters to the editor they received. Today, the majority of comments get the go-ahead online. On average, CBC publishes 75 to 80 percent of submitted comments, and at peak times receives over 1,000 comments per hour, according to the CBC moderation team.

Salon writer Gary Kamiya explained this wave of reader response in a

2007 article titled “The Readers Strike Back.” He wrote, “Before the Internet, it was easy for a journalist to behave like a sniper…firing off a shot, then ducking back down to safety. Now, people are shooting back, and it’s a bit much for the sniper to complain.”

Despite reservations, complaints, and bad experiences, Canadian news organizations cannot just ignore their comments sections. Journalists need to start changing their attitudes and recognizing the thoughtful contributions of story ideas, important questions, and identified article errors. These helpful suggestions and inquiries are overshadowed by the ghosts of bad comments past, and often get no response. When journalists converse with readers in the comments section, this can advance the journalism in ways the reporter could not achieve alone.

Commenting sections are valuable, but they are not the only platform for reader-reporter interaction. Many-to-many communication is replacing traditional journalistic one-to-many methods, and readers are now talking back. Be it Twitter, live chat, or comment response, the technology used is not as important as the outcome. News organizations are not just encouraging, but expecting journalists to engage with their readers. Comments are one oft-forgotten platform for this back-and-forth. Andrew Yates, senior producer for community and social media at CBC, explains, “In a world where there are all these platforms competing for your attention, you can’t get bogged down in one at the expense of the others.”

Ta-Nehisi Coates, a senior editor and blogger at

The Atlantic, said in

a radio interview with On the Media, he spends at least as much time curating and moderating his blog as he does writing. He repeatedly proves he values his readers’ contributions by allowing them to write whatever they please on an open blog post several times each week.

According to

an item on NPR’s All Things Considered, Yoni Appelbaum began contributing to Coates’s comments section under the username “Cynic” in 2008. Coates took notice of Cynic’s lengthy, fact-based posts and frequently conversed with him in the comments. About a year later, Coates invited Appelbaum to contribute an essay to his blog, and upon its success, approached his editor to vouch for Appelbaum. In March 2011, about three years after Cynic’s first comment, Appelbaum was offered a position at

The Atlantic, shifting from commenter to columnist. Such occurrences may be rare, but Appelbaum’s case shows there are glimmers of light to be found for journalists ready to brave the final frontier: their own readers.

Illustration by Erin McPhee.

Jon DeNunzio photographed by Maisi Julian Photography.

Barbara Kay photographed by Howard Kay.

by Davida Ander

Lindsay is a News Media Production Specialist - Multimedia at the Ryerson School of Journalism. Lindsay has been with the University for eleven years after graduating from the University with a degree in Journalism.

By Davida Ander

By Davida Ander simple: stop reading them. But for journalists, who are frequently themselves the subjects of discussion, and who are increasingly being pressured to moderate and participate in online discussions, ignoring the problem just isn’t an option anymore.

simple: stop reading them. But for journalists, who are frequently themselves the subjects of discussion, and who are increasingly being pressured to moderate and participate in online discussions, ignoring the problem just isn’t an option anymore. “Readers pose legitimate questions and participate in interesting debates in the comments, and those threads offer reporters, bloggers, columnists, and editors an opportunity to elaborate on their work and the ideas behind it,” he wrote in an October 2011 Q&A article titled “Why Don’t More Post Reporters Respond to Reader Comments?”

“Readers pose legitimate questions and participate in interesting debates in the comments, and those threads offer reporters, bloggers, columnists, and editors an opportunity to elaborate on their work and the ideas behind it,” he wrote in an October 2011 Q&A article titled “Why Don’t More Post Reporters Respond to Reader Comments?”