Journalism’s empty calories: why some personal essays leave us feeling guilty

When writers turn to their own lives for subject matter, they can make a quick buck and save editors time and hassle. But what about readers?

One of Hazlitt’s most popular pieces is also one of its most hated. Last July, the Random House of Canada online publication ran “How to make love in America,” a 3,619-word personal account by Sarah Nicole Prickett about her transience in her 20s. The piece had no interviews, no research and no original reporting. It simply documented Prickett’s self-searching years spent travelling, centering mostly on what happened as she and her lover sped across America during a 10-day road trip. The piece was intensely confessional: early on, Prickett recalls a time in Istanbul when “a supermodel’s baby-daddy taught me to do coke the way Marianne Faithful had taught him to do coke, on the end of moist joints like Lik-A-Stiks, while he fucked me.” It was completely self-involved, but wildly successful.

Still, not everyone appreciated the personal account. “Is it possible to be so deranged on yourself?” one commenter asked. “Too many sentences are there to be pleased with themselves rather than truly transmit meaning,” another complained. The response was no surprise: critics of personal essays regularly accuse them of being too navel-gazing.

But as freelance budgets shrink and editors need to churn out more stories in less time, personal essay writing is becoming increasingly common. This is particularly true online, where deadlines are tighter and editors fight to attract the most clicks possible. While personal essays don’t always include the research, reporting and analysis expected in high quality pieces of journalism, when they’re done well they give readers a sense of connection and identification. But in their rush to produce personal pieces, writers and editors don’t always put good storytelling first.

It’s important to draw the distinction between personal journalism and personal essay writing. “In one word: it’s reporting,” says Ian Pearson, a former editor at the Banff Centre’s Literary Journalism program. He believes that to be journalistically sound, an essay must go beyond mere confession to involve other people, facts and voices. He highlights writers such as Ian Brown , Marni Jackson and Katrina Onstad, who often insert themselves into their work, but supplement their involvement with thorough research. Their pieces are ultimately not about them, but about something much broader.

To Pearson, personal reported pieces and personal essays each have their place. Unreported essays are valuable when they are original, cleanly written, and offer insightful, nuanced or engaging takes on topics. Pearson cites the short pieces that appear in print and online in The Globe and Mail’s Facts and Arguments section as examples of worthwhile personal essays. Contributors are rarely journalists, and they seldom include any research or original reporting in their work. But Jane Gadd, the section’s editor, says readers enjoy the break the essays give them from depressing news stories. They also get a much-valued sense of connection from the candid accounts of strangers’ experiences. “It’s one of the few windows we get on real lives of the people,” Gadd says. “It’s sort of like meeting somebody on a bus or a train and having a conversation.”

The Globe benefits financially from Facts and Arguments. While the publication used to pay for each story, it’s now free content. In addition, the page is one of the most read in the paper, and often has a paid ad on it. This popularity hasn’t translated online yet, but Gadd expects that better search engine optimized headlines and more prominence on the homepage will change that soon.

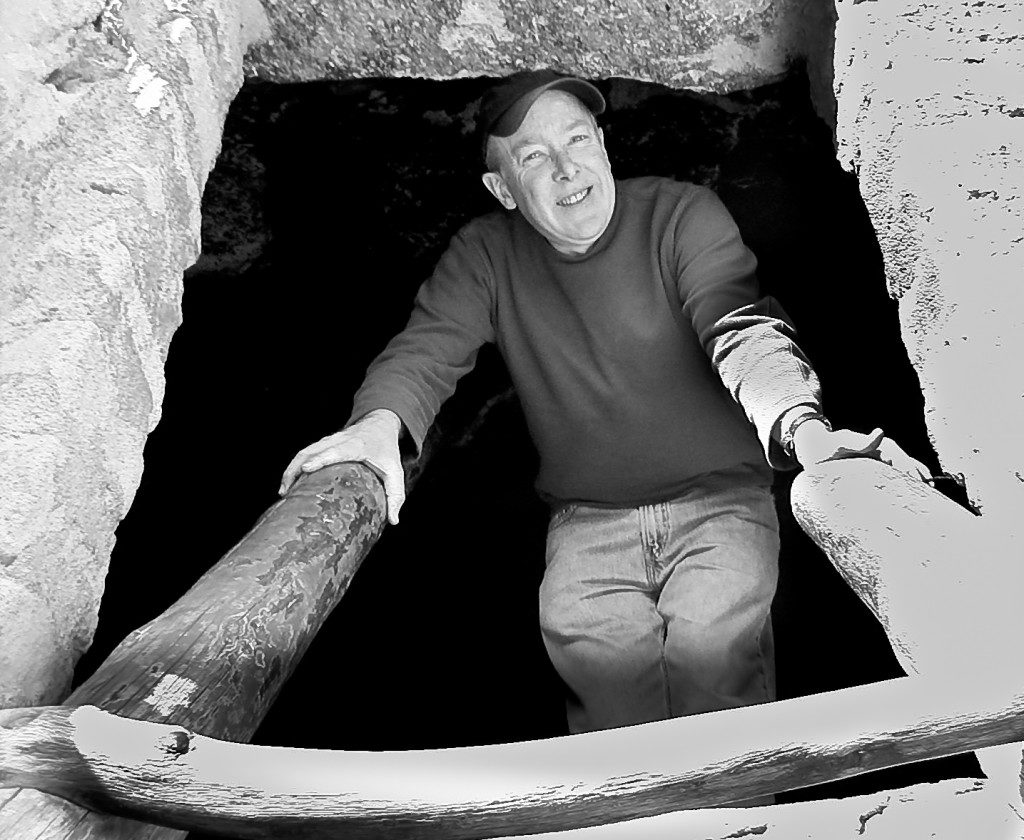

Editor Ian Pearson says personal essays can be valuable pieces CREDIT: SUE GRIMBLY

Publications also benefit from personal essays in less obvious ways. Jordan Ginsberg, a senior editor at Hazlitt, says that running a certain ratio of personal essays allows editors to post more content frequently. Often, Ginsberg says, mastheads can turn around multiple essays in the time it would take to work with a single long, reported feature. And without taking the time to research, interview and transcribe, writers can sometimes be assigned and file stories within a day.

Writers, particularly young freelancers who have to churn out as many pieces as possible to pay their bills, like that they can write personal essays quickly. The stagnation of freelance rates hasn’t helped. Pearson remembers the late 1970s, when Weekend magazine announced it would pay a dollar a word. “We were rejoicing,” he says. Three decades later, magazines that pay that rate are in the upper echelon. “It’s a joke what freelancers are paid,” Pearson says. “So if someone’s writing for a living they definitely have to consider what the quickest way to do something is.”

But what’s good for writers and editors isn’t always good for readers. Clickbait such as Salon’s “Is the Babysitter on Heroin?” and platitude-ridden confessionals such as The Huffington Post’s “Single and 40: What I Know About Love” is increasingly pervasive online. These pieces serve not to enlighten readers, but to attract eyeballs. And while their sensationalism can be exciting and their simplicity makes them easy to digest, they often offer readers nothing more. “Single and 40,” for example, is rife with generalizations: “I’ve learned that men want love too, but are sometimes unable to be vulnerable to it. I’ve learned that women want love too, but are made to feel vulnerable by it.” Thought Catalog is even more simplistic, offering readers thousands of outrageous confessionals—many written in list form—including the recent “10 Celebrities I’d Sleep With And My Friends Don’t Understand Why.” These pieces read more like blog posts or diary entries than meaningful, polished, publishable pieces of writing. For a personal piece to go beyond sensational confession or simple self-absorption, it must reveal a wider universal truth. There should be a takeaway for readers—a lesson, or a novel take on a specific topic—not just a rant about the writer’s own experience or opinion. Just as reported pieces must provide analysis of a timely issue or event, personal essays should offer analytic insights—and most importantly, no listicles. As Ginsberg says, “You don’t want to be Thought Catalog if you don’t have to be.”

Related Posts

Mental health: why journalists don’t get help in the workplace

Mental health: why journalists don’t get help in the workplace Sally Armstrong: the editor who changed women’s magazines

Sally Armstrong: the editor who changed women’s magazines Stars and Stripes: how entertainment journalism forsakes homegrown stories in favour of U.S. ones

Stars and Stripes: how entertainment journalism forsakes homegrown stories in favour of U.S. ones I don’t always play by hometown rules

I don’t always play by hometown rules I don’t always play by hometown rules

I don’t always play by hometown rules Breaking faith: are religious newspapers reporting or preaching?

Breaking faith: are religious newspapers reporting or preaching?

by Megan Jones

Megan Jones was the Editor for the Spring 2014 issue of Ryerson Review of Journalism.