Spoiling for a Fight

Two Toronto hospitals, two in-depth series, two newspapers... same day. How did it happen? How did they get access? And what was in it for the hospitals? A behind-the-scenes look

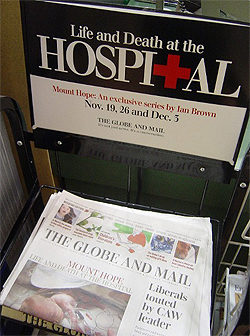

The day before her “Situation Critical” series on Sunnybrook hospital’s critical care unit was set to be published in The Toronto Star, health policy reporter Tanya Talaga caught a glimpse of an open spread of that day’s edition of The Globe and Mail on a colleague’s desk. A half-page ad jumped out at her: “Life and death at the hospital. What’s really going on in Canadian hospitals? Find out from Ian Brown on the inside. Mount Hope. Exclusive series.” The publication start date, November 19, was the same as hers. “When I saw the ad, I was filled with fear,” she says. “How is it they’re publishing the same day as us?”

Talaga was floored. More than half a year earlier, Sunnybrook had offered to open its doors to her, whose previous stories about the hospital had built her reputation among officials. In response, Talaga proposed a three-month stay with a photographer in the hospital’s critical care unit (CRCU), the largest in the country. For Talaga, it was a perfect opportunity to see the “different world” of the hospital, do justice to a complicated story and find great stories during the usually slow summer on the health beat.

Talaga was floored. More than half a year earlier, Sunnybrook had offered to open its doors to her, whose previous stories about the hospital had built her reputation among officials. In response, Talaga proposed a three-month stay with a photographer in the hospital’s critical care unit (CRCU), the largest in the country. For Talaga, it was a perfect opportunity to see the “different world” of the hospital, do justice to a complicated story and find great stories during the usually slow summer on the health beat.

Around the same time as Talaga’s April lunch meeting with Sunnybrook hospital officials, Judith John was on call at Mount Sinai Hospital for the first time. The vice-president of communications and marketing was new to the job and, upon witnessing an emergency, was amazed at how quickly and efficiently the hospital team sprung into action. John says the intensity, decision-making and lack of cynicism among hospital staff struck her as a “revelation.”

John had run into Globe editor Edward Greenspon in February and suggested the paper do an in-depth series on Mount Sinai. She sent him a follow-up email in June, reiterating the idea. “I’m kind of a pest,” she says, “but a pleasant one.” Her persistence eventually paid off, culminating in an August 15 meeting betweenGlobe editors and Mount Sinai officials.

There is no denying the story-telling power of both series, but why would a hospital give a reporter a security pass and floor plans, and do everything in its power to facilitate the reporting? When asked what’s in it for them, hospital officials are upfront. They hoped to create a “halo effect” in the minds of stakeholders, one that would also help in the recruitment of doctors and nurses. The fact that the Star and the Globe ended up competing head to head overshadowed a thornier issue – whether or not two major newspapers were being used by two hospitals, with their considerable editorial efforts ultimately being moulded into medical public relations strategies.

There is no question about the doors being swung wide open to accommodate the press. Along with Starphotographer Rick Madonik, Talaga spent three months at Sunnybrook, from July to September. Just as Talaga was wrapping up her reporting, the Globe‘s senior feature writer Ian Brown was beginning his. A couple of weeks after the meeting between the Globe and Mount Sinai, Brown and photographer Kevin Van Paassen were on site at the hospital, where they would spend the next two months. But while Talaga remained in the dark about the rival paper’s series until the day before publication, the Globe found out in September that the Star had a reporter at Sunnybrook.

This discovery prompted workers at the Globe to roll up their sleeves and work faster. “We had some intelligence from the Star that this writer had not yet begun to write,” says Brown. And when the Globe found out the Star‘s publication date, about a week in advance, it broke into full speed to match it.

This discovery prompted workers at the Globe to roll up their sleeves and work faster. “We had some intelligence from the Star that this writer had not yet begun to write,” says Brown. And when the Globe found out the Star‘s publication date, about a week in advance, it broke into full speed to match it.

“Basically what happened was that somebody said you’ve got a week, the Star‘s publishing next Saturday,” says Brown. “We didn’t want to appear after them, so we mobilized heaven and earth to get out when they came out.”

Exactly who spilled the beans about the Star‘s publication date is unclear. But, according to Globe publisher and CEO Phillip Crawley, it’s not at all unusual. “Newsrooms generally are fairly leaky places,” he says. “An awful lot of people are involved in putting together some stories… they hear about it in meetings, they see the material being processed, they see the editing roll.”

Crawley says watching what the competition is doing is a daily event, and a common feature of this rivalry is to run a “spoiler” to take the edge off the opposition’s story. Besides, what choice did the Globe have in the competitive newspaper market? If it had stuck to the original publication kick-off date in early December, “that would have looked like a copycat,” says Crawley. “We didn’t want to look as if we were running second.”

Aside from the matching start date, the series were also surprising in the amount of access given to Talaga and Brown. Traditionally, hospitals have been reluctant to grant media access in order to protect patients who are often at the most vulnerable point in their lives. Given the introduction of the Personal Health Information Protection Act in 2004, a provincial law that solidifies a patient’s right to absolute confidentiality, one might expect hospitals to be even more protective.

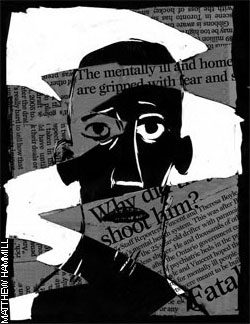

Instead, both Sunnybrook and Mount Sinai issued identity passes for the reporter and photographer assigned to the story, informed staff of what they were doing, and allowed them to accompany doctors on their rounds, in meetings, even in the operating room. Most representative of this level of access were the Star‘s photo of 19-year-old shooting victim Carlos McIntosh’s open abdomen after surgery and the Globe‘s Brown being admitted into a pandemic planning meeting to hear discussions about who would be vaccinated against the avian flu.

The primary condition of this access was that patients (or their legal guardians) had to sign consent forms before being interviewed or having their pictures taken, and a hospital official had to be the one to ask for the consent. Despite the stringent rules, Talaga and Brown were both surprised at how willing most patients were to be interviewed.

“When you’re sick, gravely ill, maybe you want to talk,” says Brown, who wonders about the government’s strict confidentiality rules. “Obviously there are very real reasons why you want the system to be confidential, but I wonder whether there isn’t an added bonus for the government in that you can never really have a full and frank conversation about the healthcare system.”

Talaga believes patients talk to show appreciation for the care they receive. “How do you say thank you to doctors or nurses or the respiratory therapist who comes in every day to suction out the mucus from your dying grandmother? By talking to the press and showing other people how great a job people at the hospital were doing, they can say thanks.”

Talaga believes patients talk to show appreciation for the care they receive. “How do you say thank you to doctors or nurses or the respiratory therapist who comes in every day to suction out the mucus from your dying grandmother? By talking to the press and showing other people how great a job people at the hospital were doing, they can say thanks.”

Taking pictures presented a whole other set of challenges. In the case of the Star‘s team, Madonik says they were able to secure a “shoot first and ask later” agreement. Because they were profiling the critical care unit, this was essential to getting any photos at all. “Most of the time people weren’t conscious or in any shape to give consent, so we had to approach family members,” he says. “And do you really want to approach them at that point when they’re making other serious decisions?” Madonik learned this when he worked on the Star‘s 2002 series about Toronto East General Hospital, “Code Zero.” He says it was “very limiting” because photos could not be taken without signed consent.

The Globe‘s agreement with Mount Sinai, which photographer Kevin Van Paassen often found frustrating, was similarly limited. “You see all these pictures happening in front of you, but unless you’ve got a pink form signed by the person you want to photograph, you can’t take that picture,” says Van Paassen. “It was sort of heartbreaking that way.”

Lynn McCauley, one of the editors on Talaga’s story, says the choice of photos used in the series was the result of many discussions. The challenge was to use pictures that were essential to the story, and that were both gripping and sensitive. She says the Star opted not to use the grittier and more troubling photos of Carlos’ injuries. “The test for me was always, if I have to go and talk to Carlos tomorrow and say why we used this photo, what was I going to tell him?” says McCauley. “You can’t just say, ‘Hell, I don’t care – it was a great photo!'”

“Do you feel like a vulture?” wonders Talaga of her experience in the CRCU. “Sometimes.” She says she did her best to tell patients’ stories in a respectful way without being exploitive or gratuitous.

Although it could always backfire on them, hospitals have recognized the importance of media coverage in raising their profiles in the public eye, especially considering most news treatments of the institutions are policy stories or cursory mentions of where victims of violence have been rushed. Brown points out that the competitive fundraising atmosphere in Toronto is a “nightmare,” and that giving the public an understanding of the services it provides is a way to raise hospital profiles. “I’ve had probably five telephone calls in the past year from hospitals saying, ‘Would you be interested in coming to the hospital and writing about us?'” says Brown. “They’re desperate to raise money.” Van Paassen says the series was a “calculated risk” on the part of Mount Sinai, since the series was anything but a “puff piece.”

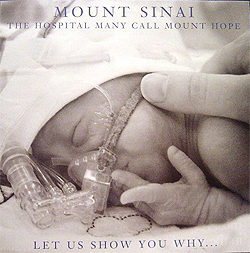

While John admits parts of the story made her wince, such as Brown’s depiction of the hospital’s cadavers and portraits of founders smoking, she was “delighted” with the series’ prominence. In fact, Mount Sinai liked the series so much it’s using it in its promotions. On December 9, an insert seeking donations for Mount Sinai appeared in the Globe. The insert used the title of the series, “Mount Hope,” quoted key characters in the articles as well as the author, and used a photo of Zachary Bastead, the premature baby profiled in the Globe series. Rob Granatstein, city hall reporter for the Toronto Sun, says he found the insert disturbing: “It doesn’t pass the smell test for me.” But Neil Campbell, the Globe‘s associate editor, says it’s routine for advertisers to use quotes from newspaper articles, as in the case of movie companies quoting reviews. “Inserts are not something we have any oversight over or really would require any oversight over,” he says.

While John admits parts of the story made her wince, such as Brown’s depiction of the hospital’s cadavers and portraits of founders smoking, she was “delighted” with the series’ prominence. In fact, Mount Sinai liked the series so much it’s using it in its promotions. On December 9, an insert seeking donations for Mount Sinai appeared in the Globe. The insert used the title of the series, “Mount Hope,” quoted key characters in the articles as well as the author, and used a photo of Zachary Bastead, the premature baby profiled in the Globe series. Rob Granatstein, city hall reporter for the Toronto Sun, says he found the insert disturbing: “It doesn’t pass the smell test for me.” But Neil Campbell, the Globe‘s associate editor, says it’s routine for advertisers to use quotes from newspaper articles, as in the case of movie companies quoting reviews. “Inserts are not something we have any oversight over or really would require any oversight over,” he says.

The same day the insert appeared, Veritas Communications commended Mount Sinai on a website called Touchdowns and Fumbles, which rates “communications plays of the week.” Granting a Triple Touchdown to Mount Sinai for the three-part series in the Globe, Veritas vice president Bill Walker wrote:

“On three consecutive Saturdays, Nov. 19, 26, and Dec. 3, the series received spectacular play. We’re talking here about the equivalent of millions of dollars worth of paid media, if you could buy it, and you simply cannot. Nor can you buy the credibility for Mount Sinai that these journalists lent through their unbiased and unfiltered reporting. Medical schools are already asking the hospital about using the series of articles in curriculum… A truly outstanding communications play. Kudos to Judith John and her communications team at the hospital for making this happen.”

While the issue of motive is a concern for editors, the main question for the reporters and photographers on the projects is which was the better story? Brown says, “I respect the Star enormously, but I think they dropped the ball, frankly. I don’t think they decided what the story was about.” Van Paassen, who says it was “nerve-racking” to find out veteran photographer Madonik was assigned to the Star‘s series, says “Situation Critical” was fantastic in its reporting and photography, but lacking in presentation. “What put us head and shoulders above the Star‘s presentation was not the content,” he says. “It was the way it was presented.”

There is no disagreement on this issue. Both Talaga and Madonik were confident in their series but jealous of the space given to their rivals at the Globe. For three consecutive Saturdays, Brown’s story was spectacularly laid out in the Focus section, with no ads, lots of white space, and more and bigger pictures. While Talaga’s seven stories ran at just under 15,000 words, Brown’s three-part series ran at about 17,000. And out of the 5,000 frames Madonik took, 22 made the paper, while 43 of Van Paassen’s 200 frames were published. Crawley says the Globe‘s series was one of the best things the paper has published in a long time, and that it needed to be given big treatment.

Giles Gherson, the Star‘s editor-in-chief, sees it differently. Happy with the Star‘s treatment of its series, he points out that because the Star has a larger circulation and a broader readership than the Globe, a more varied mix of stories is needed and there is more competition for space. “Part of the energy of a newspaper is in really adjusting to make way for breaking news,” says Gherson. “The biggest mistake you can make in a newspaper is being wedded to some advance planning that doesn’t take into consideration the news,” he says, referring to the Globe‘s front-page placement of part two of its series the weekend after the election call and during an “incredible development” in the story of the Canadian hostages held in Iraq. “In a series, you’ve got to be careful,” says Gherson. “You don’t want to overstay your welcome with readers.”

The Globe‘s promotion, which played up the series on newsstands as well as in large ads in the paper, was also much stronger than the Star‘s “tiny promos,” according to Talaga. But Gherson says the Star doesn’t need much promotion because of its large number of seven-day readers. In his view, the Globe‘s aggressive promotion was a way of obscuring the fact that the Star had a huge lead time. In fact, he says the series’ matching release date was “an act of desperation” on the Globe‘s part.

Regardless of which was better, both series have had a profound effect on all those closely involved in producing them, both in the rapport with patients and the questions raised about life and death. Talaga and Madonik visited George Hart after his wife’s funeral, and followed up with motorcycle accident victim Emily Collins in a December 22 story about her return home for the holidays. Brown and Van Paassen became good friends with Donald Townshend, who had surgery to remove cancer from his arm. “There were days we thought, ‘Oh my God, he’s going to die,'” says McCauley, Talaga’s editor, of Carlos, the gunshot victim. “I could hardly tell people the sked lines of that story without getting emotional because I just found it so tragic.” For Brown, researching and writing the series was an “emotionally harrowing” experience. “I don’t want to pretend I’m deep or anything,” he says, “but the potential was certainly there.”

Regardless of which was better, both series have had a profound effect on all those closely involved in producing them, both in the rapport with patients and the questions raised about life and death. Talaga and Madonik visited George Hart after his wife’s funeral, and followed up with motorcycle accident victim Emily Collins in a December 22 story about her return home for the holidays. Brown and Van Paassen became good friends with Donald Townshend, who had surgery to remove cancer from his arm. “There were days we thought, ‘Oh my God, he’s going to die,'” says McCauley, Talaga’s editor, of Carlos, the gunshot victim. “I could hardly tell people the sked lines of that story without getting emotional because I just found it so tragic.” For Brown, researching and writing the series was an “emotionally harrowing” experience. “I don’t want to pretend I’m deep or anything,” he says, “but the potential was certainly there.”

As Talaga ingests her required caffeine for the day in the Star‘s fourth-floor cafeteria with large glass windows overlooking the lake, I get the sense that she is wistful about her spoiled story. But she does stress, as did Brown, that the series were very different: Brown’s was a sweeping look at what life in a hospital is like, and hers had a stronger news hook, addressing issues such as gun violence.

“That was a little daunting, knowing I was going toe-to-toe with Ian Brown,” says Talaga, before adding with a smile, “but I think we danced well together.”

Sumayyah Hussein was the Head of Research for the Summer 2006 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.