The changing anatomy of a magazine

Is it time for magazines to restructure the front of book?

By Blair Mlotek and Viviane Fairbank

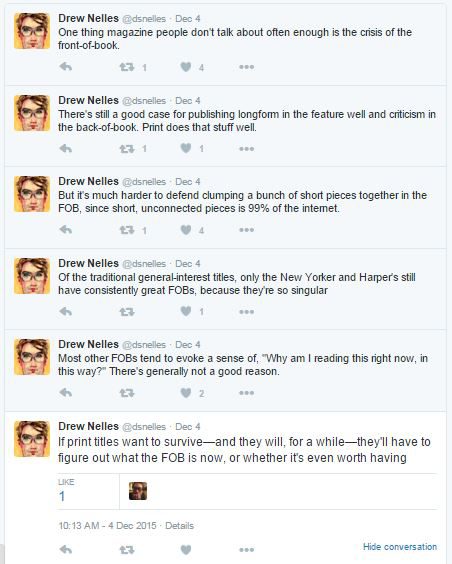

The front of book (FOB) consists of the first few pages of a magazine, with smaller pieces and graphics meant to ease a reader in before the long features. FOBs may have been relevant once, but today, when shorter articles and listicles are the majority of content found online, they don’t add value to a printed magazine. Leave FOB material for the website and longer features for the print edition, advises Drew Nelles, a freelance editor and writer now in New York, but formerly of Maisonneuve and The Walrus. Not everything is worth going to print anymore.

The solution to the “crisis of the front-of-book” may not be as drastic as cutting the section altogether (though some magazines, such as The Believer, have already taken that approach). Today, an FOB section simply has to be more singular than short, curated content. It has to have a theme or tone that is unique to a specific magazine, separate from the typical eclectic FOB style.

There’s The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town, for example, which Nelles believes to have “a life and a voice” different from others. Or Harper’s Magazine, with its Harper’s Index and Readings. Those sections are more than just padding before the crux of the magazine’s content; instead, they are part of the identities of the magazines.

But most other printed magazines, which haven’t been able to brand their FOB in the same way, may have to change their approach. Nelles says that Maisonneuve, which prints longer stories in its FOB section, was never able to determine what made something “right” for FOB, as opposed to the feature; it really only came down to page space.

Photo by Allison Baker

Catherine McIntyre handles FOB for This Magazine. To her, the FOB section has value not only for light reading material before long, text-heavy articles, but also for establishing This’s identity. “If you’re picking up a magazine and you’re reading the front section, you know what to expect to a certain extent,” McIntyre says.

McIntyre doesn’t agree that these articles are similar to web content. In fact, for This, McIntyre tries to get stories that people may have missed online. They’re not always light stories and there isn’t always a clear theme, but there is a consistency that, McIntyre says, her readers rely on. She often publishes a profile, a news story that may have been missed in daily coverage, a critical account of a certain institution and a column on feminism in the FOB section.

McIntyre thinks that readers don’t mind if the content of a magazine is similar to what’s online. The words are the same in both places, but many people still choose to read in print form. She compares it to the same romanticism that brings people to the movie theatre, even though Netflix is just a laptop away.

The argument may be old, but it applies to the entire magazine industry, including the FOB. If The New Yorker cut its Talk of the Town, McIntyre says, readers would be “unimpressed.” They would be thrown off—many wouldn’t read the magazine at all. “And yet,” she says, “you can get Talk of the Town online.”

Tell us what you think in the comments below. Should magazines get rid of the front of book?

by Blair Mlotek

Blair Mlotek is the Online Handling Editor for the Spring 2016 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.