Firebrand

At 19, Heather Robertson wrote an editorial that enflamed the college jocks, sparking a career dedicated to fearless reporting. A revealing look at Canada's feistiest journalist

Heather Robertson wanted no part of a football team.In 1961, the University of Manitoba was again considering forming a squad, even though teams had already folded twice due to high costs and low support. But “the football boys,” as Robertson called them, wanted to try again—at the expense of the students and administration. So, as editor of the school’s newspaper, The Manitoban, the 19-year-old wrote a fiery editorial denouncing the proposal. “Again this year they are peddling football—an easy, instant remedy for all the ills that affect Manitoba,” she began. “Are three expensive games per season in a makeshift stadium in foul weather against teams from places most of us have only heard about and wouldn’t particularly care to visit going to suddenly make us full of college spirit?”

Heather Robertson wanted no part of a football team.In 1961, the University of Manitoba was again considering forming a squad, even though teams had already folded twice due to high costs and low support. But “the football boys,” as Robertson called them, wanted to try again—at the expense of the students and administration. So, as editor of the school’s newspaper, The Manitoban, the 19-year-old wrote a fiery editorial denouncing the proposal. “Again this year they are peddling football—an easy, instant remedy for all the ills that affect Manitoba,” she began. “Are three expensive games per season in a makeshift stadium in foul weather against teams from places most of us have only heard about and wouldn’t particularly care to visit going to suddenly make us full of college spirit?”

The jocks called for her head. They wanted their team and they wanted Robertson fired for speaking out against it. So the student council called on her to justify her words. “She wasn’t objective!” the football fanatics argued. “It was an editorial!” she countered. As she stood inside the student centre making her case, she heard a dull roar outside as a group of protesting jocks shouted into a megaphone and demanded their team. Then, through the windows of the small room, Robertson watched in shock as the throng raised a stuffed figure by a rope around its neck. She quickly realized that the bundle of straw, with its long hair and skirt, was her effigy. It wasn’t enough to just symbolically hang her; the crowd outside wanted more. The mob lit a fire under the straw and soon “Heather Robertson” was up in flames. All this over an editorial?

The football boys were just the first of many opponents Robertson would face in her journalism career. She’d win some battles and lose others, be labelled a communist and get sued for libel. But when she was just a sheltered 19-year-old girl, inspiring a demonstration was incredibly exciting—journalism was exciting. She didn’t know it then, but the excitement wouldn’t end there.

Today, at 69, Robertson walks with a slight limp, has short white hair and wears slacks and loafers. She has a warm laugh, works on her garden and can’t help but talk about her kids (her son is a film editor who worked on the Angelina Jolie action movie Salt). But in many ways, Robertson is far from ordinary. For 15 years she fought two class action lawsuits against the largest media corporations in Canada—and won. She filed on behalf of all Canadian freelance writers who had their work reproduced on electronic databases without their knowledge, consent or compensation. The media giants paid millions.

Many journalists now associate Robertson with those landmark lawsuits. They celebrate her for standing up for her peers, keeping everyone updated on the case and, of course, for the “Heather Robertson cheques,” some in the tens of thousands of dollars. But plenty of the freelancers who were thrilled to cash those cheques know little about the woman who fought for them. They don’t know about her 50-year career, her 18 books and her three novels, or her role in the creation of the Professional Writers Association of Canada. Though Robertson’s lawsuits have been important to Canadian journalists, they are just the latest battle in a career marked by activism. “She was a muckraker,” says Don Obe, her editor at Toronto Life. “She was out to right wrongs and she was her whole magazine-writing career.”

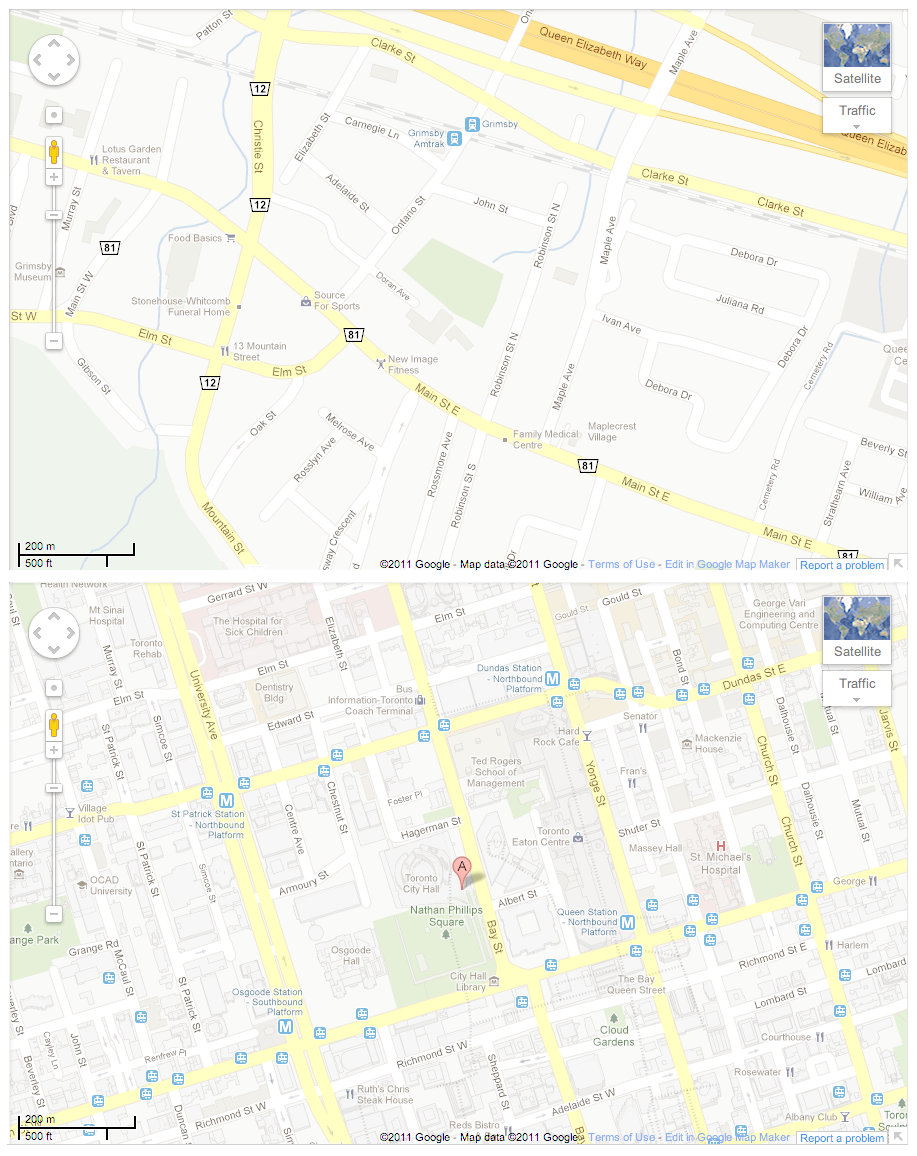

“It was in my blood to stick it to the corporation,” says Robertson, who was born in Winnipeg in 1942. Her grandfather emigrated from Scotland, worked as a pattern-maker for the Canadian National Railway and took part in the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919. “He was a proud labour man,” she says. “I still have his copy of Das Kapital by Karl Marx on my bookshelf.” Unions, the CCF, medicare—these ideas, prominent in Western Canada, were a formative influence on Robertson. She now lives in King City, just north of Toronto, but still longs for the prairie.

In 1964, after she completed a master’s in English literature at Columbia University, which she attended on a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, the school offered her a scholarship to do her PhD. Her thesis adviser told her the degree would make it easy to find work at a New England women’s college. Robertson’s whole future flashed before her eyes. “I saw myself as this hag in a black robe—spinster—teaching these girls with the perfectly coiffed pageboy, blond hair, coming from these wealthy families—the cream of the Boston crop, whatever—in some sort of rusticated, rural, ivy-covered college,” she recalls in mock horror. Then, from the depths of her subconscious, where the memory of the exciting Manitoban demonstrations lived, she blurted out a revelation that surprised both her and her adviser: “I’m tired of reading books! I want to write them.”

She got her start by landing a job at the Winnipeg Tribune, where she learned a lot from the fraternity of heavy-drinking, crude and talented reporters. “They believed in truth-telling and accurate reporting,” she says. “So they taught me a great deal about standards and being courageous to tell the story that you found, not the story that somebody thought that you should be telling.”

Robertson was part of a new generation of female journalists in the 1960s. Unlike the veteran male reporters working next to her, she was university educated. And unlike most of the women who came before her, she didn’t write about social gatherings and bazaars for the women’s pages—she reported. In her 1980 piece, “The Last of the Terrible Men,” in Canadian Newspapers: The Inside Story, she reflected on the new wave she was a part of. “We had no tits. It had been customary to measure the talent of female staff members at the Tribune by the size of their bra cups; the women’s editor was a statuesque 38D, columnist Ann Henry a stunning 36 triple C. We were all As.”

In 1965, the First Nations of Kenora staged a peaceful demonstration demanding recognition and equality. The protests captivated Robertson. Just 23, she entered a 1966 Imperial Tobacco contest to write a book about Canada in the year 2000. Her theme: the status of the country’s Aboriginal Peoples. With $3,000 and a deadline of September 1, 1967, Robertson left theTribune and set off in her dad’s 1958 Nash Rambler. The Department of Indian Affairs warned her of the “bad Indians” to avoid. She sought them out first. For eight months Robertson travelled the Prairies visiting aboriginal reserves by car, train and even plane. She kept her distance and did not stay overnight on the reserves. “I thought, I’m a journalist, I’m not a sociologist. I’m not going to pretend to be one of these people.”

James Lorimer and Co. published Reservations Are for Indians in 1970. It was the first time a white journalist had approached the social problems facing Canada’s aboriginal population in such depth. Robertson discussed suicide, alcoholism, dependency, backward government policies, treaties and culpability. In one chapter, Robertson described the “mudlarks” of The Pas, Manitoba. “These pathetic little dark girls are not seductive, bundled up against the cold in ski pants and ugly nylon jackets, shivering,” she wrote. “It is not really accurate to call these women and girls prostitutes. There is so little money involved and they are so apologetic, unassuming, and unprofessional, they will go with a man for nothing, just on a gamble that something will turn up.” Some Aboriginal readers were so offended that investigators were sent to The Pas to prove the mudlarks did not exist. But they did. When Lorimer accompanied Robertson to a public debate with aboriginal leaders in Flin Flon, he was impressed that, despite her relative inexperience, she didn’t hide from the story she wrote or the people she angered.

Though her first book was controversial, it sold. In 1971, following that success, Maclean’s editor Peter C. Newman hired Robertson to write a monthly television column. “Nobody in the country was writing as well as she,” he says. “I got into huge trouble when I was visiting Winnipeg and interviewed on the CBC. I was asked, ‘Why don’t you hire more people from Winnipeg?’ and I remember saying, ‘I’d give my right nut to find another Heather Robertson.’” A typical column included at least one jab at CBC’s uninspired adaptation of the hit novel The Whiteoaks of Jalna, but she always offered more than just what was or wasn’t good on TV. Instead, Robertson used television to present a social critique and discuss important issues, says Newman. In her November 1971 column, for example, she took on the medium’s inherent biases. “Like all class systems, television tends to exploit the people it excludes. Ethnic groups, hard hats, rural people, religious sects make it onto TV only as part of a news item or as subjects of a documentary,” she wrote. “They are categorized, observed, manipulated, interviewed, photographed, edited, scripted and packaged.” The networks, she argued, needed to put “real people” on the airwaves.

Robertson wasn’t afraid to express her opinions—no matter how contentious. In an April 1975 column titled “Confessions of a Canadian Chauvinist Pig,” Robertson voiced her intense anti-Americanism. “I am sick of all the snivelling hand-wringing cant about our good friend and neighbour to the south, the longest undefended border in the world blah blah while this good friend, violent and exploitive abroad and corrupt at home, treats us with contempt and robs us blind,” she wrote. “I suspect most of us have our revolution/invasion fantasies—I confess to a desire to toss a hand grenade into every American camper I pass on the highway.”

Months later, Elaine Dewar, the editor on the piece, found out that the column had infuriated the higher-ups at the magazine. “The plan was: throw those women out the door,” she recalls. Yet again, somebody wanted Robertson dropped. Though she and Dewar stayed, Maclean’s soon changed from a monthly to a bi-weekly newsmagazine (on its way to becoming the weekly it is today) and Robertson didn’t want to be confined to a column. “I sort of have a theory that columnists tend to burn out after a few years,” she says. “You’ve said what you have to say.”

But she was far from finished pissing people off. By 1979, working as a freelancer, she visited the Royal Ontario Museum and found it a dusty relic in disarray. “The collection is a mind-boggling hodgepodge,” she wrote in a Toronto Life story called “The Royal Ontario Muddle.” “The only motive for some of the displays seems to be vanity—the donor’s name on the label is the first thing I notice.” She saved her harshest criticisms for the dubious ways the museum attained its collection. “The cheapest way to acquire treasure was to rob tombs; much of the ROM is a necropolis.”

The magazine’s publisher, Michael de Pencier, was on the museum’s board of directors and wanted the piece killed. But Obe defended it because he believed it was “a good, irreverent piece for Toronto Life to be presenting.” Working as the middleman, he attempted to squeeze some concessions out of Robertson. “She was prickly. She was standing her ground and she wasn’t prepared to give very much at all.” Obe says de Pencier gave more than she did. In the end, she made some minor compromises and agreed to a byline that read “Opinion by Heather Robertson.” She maintains she simply wrote what she found and it wasn’t her job to keep the publisher in mind. But de Pencier wasn’t the only one upset with the piece, says Obe. “We got all kinds of letters saying that this communist from Winnipeg was out to destroy our museum.”

When Robertson started freelancing in 1971, editors could assign her a story, make her write three or four drafts, kill it and never pay her a cent. Veteran writers never saw rates increase and discussing how much a writer made was taboo. So, Robertson and some colleagues, including June Callwood, Alan Edmonds, Erna Paris and Myrna Kostash, tried to improve the situation. Their idea was that strength in numbers would lead to greater respect. “We wanted acknowledgement from people that paid us the cheques that we were professionals,” says Kostash. In 1976, they formed the Periodical Writers Association of Canada (PWAC) and created a freelancing contract that established kill fees and conduct standards. But few editors signed on and one dismissed them as a pack of lone wolves. “They said we would disappear in a matter of months,” says Robertson. Though they didn’t get much support from management, she believes the fact that freelancers would actually join together caused quite the stir in the publishing industry. Today, PWAC (which has since changed the P in its name from Periodical to Professional) still uses a standard contract and has 21 chapters and more than 600 members.

Then, in 1996, The Globe and Mail demanded its freelance writers sign contracts giving all rights to all media, in perpetuity. A freelancer for more than two decades, Robertson had always dealt with editors verbally, so she found these new contracts alarming. “For them suddenly to start wanting all of these rights, we got to thinking, well, what are they doing here? Are they trying to legitimize something?” The internet was still far from a household convenience at the time, so Robertson went to the Toronto Reference Library and asked the librarians to search her name on the InfoGlobe database. They found a recent excerpt of her book, Driving Force, which had been published in Report on Business Magazine in October 1995. She hadn’t given anyone the right to put it online; neither had her agent or her publishers. Many of her colleagues’ work was online as well. They were furious. After failed negotiations with the Globe, Elaine Dewar suggested the freelancers band together and sue.

Class action law was only four years old in Ontario when Robertson and her colleagues, including Dewar and Callwood, approached Michael McGowan (who was recommended to her by a friend because he “never quits”) and his associate, Kirk Baert, to take on their case. “The freelancers believed that this wasn’t permitted, that they had only sold a one-time use of the articles and that publishers didn’t have any right to sell it again and again and again by putting it on a database,” says Baert. The writers filed a lawsuit against Thomson Corporation, its affiliate companies and what was then Bell Globemedia Publishing. Because Robertson’s book excerpt had been printed in the Globe and her publishers had a contract, which said nothing of electronic rights, she was an obvious choice to represent the class.

And by this point in her career, Robertson had largely moved on from features to books. She’d written eight non-fiction books on topics that ranged from the life of Kenny Leishman, one of Canada’s most notorious thieves (The Flying Bandit), to profiles of four Prairie towns (Grass Roots) to Canadian art and literature of the two world wars (A Terrible Beauty: The Art of Canada at War). She also had three novels to her credit because she felt writers weren’t—and still aren’t—considered real writers unless they write fiction. Her first, Willie: A Romance, about a love triangle involving Prime Minster William Lyon Mackenzie King, won both the Books in Canada Best First Novel Award and the Canadian Authors Association Fiction Prize. Because she was primarily an author in 1996, it was easier for Robertson to agree to represent the class in the lawsuit. “I wasn’t dependent on journalism for my income. So, I could offend these people,” she says with a laugh. And she wanted to take the media corporations on. Harkening back to her Scottish roots, Robertson says, “Here I was, this middle-aged Canadian woman, suddenly being robbed of my creative work by a laird. It’s one of those blinding moments. I guess in a way, I saw it as this tremendous challenge. I reached for my dirk and off I went.”

In 2003, Robertson launched a second suit against ProQuest, Rogers, Toronto Star Newspapers, Canwest and CEDROM, which she calls “Robertson vs. Everybody Else.” Three years later, the Supreme Court of Canada found that “newspaper publishers own the copyright in their newspapers and have a right to reproduce a substantial part of that newspaper but do not have the right, without the consent of the author, to reproduce individual articles.” In 2009, the Thomson suit was settled and the corporations had to pay $11 million to the class. Almost 850 Canadian freelancers who had filed claims split more than $5 million. They received anywhere from $1 to just under $55,000; the average claim was $7,500. Every settlement was calculated using the same formula—even Robertson’s. For the hundreds of hours she put in each year toward the lawsuits, she received only the minor amount of $5,000 for the time she committed to the litigation on behalf of the class. But she doesn’t seem to mind and even downplays the significance of her role as class representative. “It wasn’t that onerous, just sort of keeping people up to date with what was going on,” she says. “It was a collective effort.”

Though freelancers are thankful that Robertson stood up for her peers, some question whether these lawsuits have actually benefited writers in the long run. Kim Pittaway, who has been working for magazines since the late 1980s, says the suits are important because they articulate writers’ rights to their own work. However, she says the suits haven’t necessarily helped anyone maintain control over those rights because lawyers have simply created more comprehensive contracts, demanding rights to all media “now known or ever to be discovered” without increasing fees. But Baert says these contracts are not the media corporations’ response to the class actions. In fact, the Globe’s contract was the catalyst that brought Robertson to court in the first place. “The fight is just beginning now,” says Robertson. “We’ve got our copyright but these contracts are still there. So we now have to deal with contract negotiations so that we get a fair compensation.”

But that’s a fight for other writers. After spending 15 years on the class actions, it’s now time for Robertson to think about her future. She’s had an idea for a new novel—a family saga—in her head for years and maybe she’ll try to put the pieces together. But her biggest task is figuring out what to do now that the class actions are over. “When you’re carrying a bag for 15 years, then all of a sudden it’s gone, it’s a funny feeling.”

Robertson sits in the middle of a canoe as her friendsand guides Paul Pepperall and Ann Love paddle her up the Nottawasaga River. It’s a miserable, cold October day in 2009 and the 67-year-old is doing research for a book. They are searching for a long forgotten waterway called Willow Creek. She later described the trip in Walking into Wilderness: The Toronto Carrying Place and Nine Mile Portage: “As we enter the swamp we are engulfed by dense, drowned forest, a monochromatic landscape of greens and browns. It has been an unusually wet summer, and rivulets are running into the river from all directions. I have been warned that canoeists get lost in this watery labyrinth.” For hours, Pepperall and Love manoeuvre between dead logs and fight the strong current while Robertson scours the landscape and her maps for the inky-black creek. At last they finally see it. “We stop, and look at each other amazed,” she wrote. “We have made a discovery!”

Nearly two years after that adventure, on a rainy June morning, Robertson sits in the front row of an auditorium in north Toronto waiting to receive her award for Walking into Wilderness from the Ontario Historical Society. The presenter says, “This is a well-conceived, well-researched, well-written and beautifully designed book of regional history.” A month earlier, Robertson learned her second class action had settled (and the class would share $7.9 million). But today, she isn’t celebrating her successful lawsuits; instead, others are celebrating her for her writing. And that’s just as it should be.

by Regan Reid

Regan Ray was the Editor for the Summer 2007 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.