The Question of Rape

Heated rhetoric aside, are journalists out of touch with the risks female reporters face in conflict zones?

On Day 11 of the Egyptian uprising against the 30-year rule of President Hosni Mubarak, Globe and Mail correspondent Sonia Verma and her colleague Patrick Martin were walking through what she describes as the “nouveau riche” neighbourhood of Mohandeseen. Verma was filming a pro-Mubarak crowd marching in the streets. At first this all-male crowd seemed friendly, some of its participants even smiling and waving flags for the camera. Suddenly, though, the scene turned menacing as some armed marchers charged Verma and Martin. As she recalls, “We were basically surrounded by this mob on all sides and they were becoming violent toward us.”

On Day 11 of the Egyptian uprising against the 30-year rule of President Hosni Mubarak, Globe and Mail correspondent Sonia Verma and her colleague Patrick Martin were walking through what she describes as the “nouveau riche” neighbourhood of Mohandeseen. Verma was filming a pro-Mubarak crowd marching in the streets. At first this all-male crowd seemed friendly, some of its participants even smiling and waving flags for the camera. Suddenly, though, the scene turned menacing as some armed marchers charged Verma and Martin. As she recalls, “We were basically surrounded by this mob on all sides and they were becoming violent toward us.”

Fortunately, a security guard from a nearby apartment block emerged, firing gunshots into the air. The crowd froze. He grabbed the two journalists and hustled them into an apartment building. A woman living on the first floor took the three of them in. They stayed for several hours until the mob moved on. It was only after the security guard had escorted the two reporters back to their hotel that Verma realized she had deep bruises along her back and one arm.

Today the incident is an afterthought. But that day in the apartment in Mohandeseen, Verma’s immediate concerns were escaping and the safety of the family who sheltered her, leaving her no time to think about her daughters: Annie, then three, and Sarah Jane, two.

It was thinking about her own two children—ages one and two—that may have kept Lara Logan alive on February 11, 2011, the day Mubarak resigned from office. As is widely known, the CBS News chief foreign correspondent was not as lucky as Verma when she ventured into the celebratory crowd in Cairo’s Tahrir Square with her bodyguard, producer, fixer, cameraman and two Egyptian drivers. As she noted later about the response to Mubarak stepping down, “It was like unleashing a champagne cork on Egypt.”

But the mood wasn’t purely triumphant. Logan’s fixer, Bahaa, could hear men shouting in Arabic to attack her.

In a 60 Minutes interview, Logan recounted how, after she was forcefully separated from her crew, men began to grab her everywhere. They stripped her of clothing, pulled at her hair, scalp and limbs, beat her with sticks and raped her with their hands. She believed she was going to die and had essentially given up. Then she thought, “I can’t believe I just let them kill me…that I just gave in, that I gave up on my children so easily.” She decided to survive for them by surrendering to the assault.

In response to the attack on Logan, the Toronto Sun’s Peter Worthington wrote an inflammatory column that posed the question, “Should women journalists with small children at home, be covering violent stories or putting themselves at risk?” His answer: “It’s a form of self-indulgence and abdication of a higher responsibility to family.” Logan’s decision to report from Egypt was, he said, “the right thing for her to do journalistically—unless, of course, she had small children, which was the case. Her son…should have taken precedent over her wishes to cover the world’s biggest story for the moment.” Worthington continued, “This holds true for any woman covering wars or revolutions.” (Worthington later clarified that by small children he meant those under age five.)

Not surprisingly, the response among journalists was almost universally negative. Jan Wong, a former Globe reporter, called him a misogynist. Stephanie Nolen, the Globe’s South Asia bureau chief, was also dismissive: “It’s not 1940.… My partner is every bit as engaged, as involved, as important to my children, and it would be an equally devastating loss for my children if either of us were killed. And I think it is profoundly insulting, not only to women, but to men who are parents and care about their children, to suggest otherwise.” Wilf Dinnick, Verma’s husband, wrote an open letter to Worthington demanding an apology and indicating that Verma chose not to write about her mob experience in Egypt “because she feared sexist and antiquated views like yours might take away from the importance of the story in Egypt.” He concluded: “Perhaps it is not a coincidence that Middle Eastern dictators of your vintage are being tossed out of power for being so out of touch.”

Heated rhetoric aside, is the journalistic community out of touch with the particular risks faced by female reporters, mothers or not, in conflict zones?

Even as the New York–based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) launched an investigation into sexual violence as an occupational hazard, more incidents surfaced. A little more than a month after Logan’s ordeal, New York Times photojournalist Lynsey Addario was released from six days of captivity in Libya, during which she was repeatedly sexually assaulted. Four weeks later, CBC reporter Mellissa Fung’s memoir Under an Afghan Sky, about her 2008 kidnapping that lead to 28 days as a hostage in Afghanistan, revealed she had been raped while in captivity.

To research the CPJ paper, senior editor Lauren Wolfe spoke with more than 50 women who reported assaults ranging from aggressive physical harassment to groping to gang rape. (She notes that male reporters, to a much lesser degree, are also at risk for rape.) In the resulting report, “The Silencing Crime: Sexual Violence and Journalists,” released in June, she charged that “sexual violence has remained a dark, largely unexplored corner.”

Four years before Wolfe’s report, Judith Matloff, now an adjunct professor at Columbia Journalism School and a former long-time foreign correspondent, wrote “Unspoken,” about the sexual abuse experienced by female foreign reporters. The piece appeared in the May/June 2007 issue of the Columbia Journalism Review, but went largely unnoticed. Only in the wake of the Logan episode, when CJR featured her article prominently on the website, did 30 news organizations interview Matloff. Today, she says the Logan episode “really blew the lid off what had basically been a dirty secret in the industry for a long time.”

Gillian Findlay of CBC’s the fifth estate regrets not revealing that she found herself at the mercy of groping hands while caught in a Baghdad crowd in 1999. It wasn’t until March 2011 that Findlay publicly spoke about the incident for the first time, at a symposium on female reporters. She recalled how she had been separated from her crew and was terrified before her fixer came to the rescue. Now, Findlay describes what kept her silent: “I didn’t want my male colleagues—at the time most of my colleagues were male—to look at me differently or feel differently about me or feel they had some responsibility to take care of me. I just knew it wasn’t good if I talked about it.”

In “Unspoken,” Matloff tells a more extreme version of Findlay’s experience: the case of a photographer working in India who was set upon by a group of men “baying for sex.” Rescued at the last minute, she later decided not to tell her editors what happened. “I put myself out there equal to the boys,” she says. “I didn’t want to be seen in any way as weaker.”

Wolfe and Matloff also discuss women’s feelings of shame, their fear of being labelled troublemakers and their concern that they won’t be believed. But both highlight this issue of self-image. In her CJR article, Matloff wrote, “[T]he compulsion to be part of the macho club is so fierce that women often don’t tell their bosses.” More recently, she elaborated: “The bosses don’t know about it because the women don’t talk about it. And then because the bosses don’t talk about it, the next generation of women don’t talk about it.” Even today, those bosses are predominantly male—the foreign editors for the National Post, the Toronto Star, CTV, the Canadian Press and the Globe are all men.

Ann Rauhala was one of the exceptions when she served as the Globe’s foreign editor from 1989 to 1994. Based on her experience, she speculates that having a female boss could make women dealing with sexual abuse feel safer speaking up and more likely to seek help. She adds: “It might make editors [and] newsrooms more inclined to make sure that everybody who goes out there gets training and education that takes into account the possibility of sexual assault.”

On the other hand, Stephen Northfield, the Globe’s foreign editor for the last six years, doesn’t see safety as a gender-specific issue. “We support everybody who wants to do this kind of work,” he says. The paper has 12 staff foreign correspondents based overseas, three of whom are women, in addition to Verma, whom the paper parachutes in.

Of course, as the Globe figures suggest, it’s no longer unusual to find women in the field, unlike the days of Kit Coleman. The journalist and war correspondent for Toronto’s Daily Mail and Empire in the late 1800s to early 1900s, was credited with being one of the first female foreign correspondents. Even in the 1970s and ’80s, female correspondents such as CBC’s former Beirut bureau chief Ann Medina, who covered mostly the Middle East, were a novelty.

The types of conflicts journalists cover have been transformed too. “Things started to change in the 1990s with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the end of the Cold War, the end of formalized conflict,” says Paul Knox, a former Globe foreign editor and reporter. In an email, Sherry Ricchiardi, senior writer for the American Journalism Review and professor at Indiana University’s School of Journalism, explained the implications of the shift from wars between states to wars within them. In Libya, for example, the conflict originated within the country between opposing factions. Thanks to “no designated front lines or definite chain of command,” she says, “danger, including sexual violence, is far greater.”

Though Matloff agrees, she emphasizes that rape can happen in all kinds of situations. “Most of the cases I documented occurred in hotel rooms—from Russia to Iraq—or in rowdy crowds in such places as Pakistan and Egypt,” she says, adding that journalists can also be abused when detained.

How aggressors perceive journalists generally has also changed. Knox notes that there used to be an unwritten rule that journalists, male or female, weren’t targets. One example he gives from his days reporting in Latin and Central America is the practice of pasting the letters “TV” (an international code for journalist) on vehicles. To do that today would be like painting a “target on your back,” Knox says, because reporters are no longer viewed as independent or as likely to provide fair coverage. “They’re seen in many ways as agents of one side.” This also translates into greater peril for female reporters, according to Melissa Soalt, a women’s defence expert who was inducted into Black Belt Magazine’s Hall of Fame in 2002. The combination of reporters viewed as targets and blurred enemy lines means more risk. “When all bets are off and chaos prevails and men are armed and law and order and conventional boundaries break down, you have prime conditions for attack against journalists,” she says. “And for women that means targeted for sexual assault.”

Still, Tony Burman suggests that journalists who live and work in the developing world are more apt to be aware of the risks. The former CBC News editor-in-chief and, more recently, Al Jazeera English managing director says, “From the Al Jazeera perspective, some of our most prominent and most experienced correspondents are women and they [have been] dealing with these challenges for years.”

For everybody else, there’s hostile environment training.

To prepare their staff for modern-day conflict, many major media outlets send newbie foreign reporters to training conducted by former British Royal Marines and U.K. Special Forces who work for companies such as Centurion Risk Assessment Services Ltd. and AKE Ltd., respectively. Journalists learn how not to die of dehydration, how to identify certain weapons just by their signature noise and how to be a good hostage—essentially, how to stay alive. At Centurion, they also undergo mock kidnappings. In her 2011 book, Decade of Fear: Reporting from Terrorism’s Grey Zone, Michelle Shephard, national security reporter for the Star, recalls the week she spent in Virginia at Centurion’s U.S. camp in 2006. She writes of the instructors’ “Oscar-worthy performances” as they “threw burlap sacks over our heads and then had us march, kneel, lie motionless face down in the dirt in a drill that felt all too real.”

Such verisimilitude isn’t cheap: AKE charges $3,950 (U.S.) for a five-day course; Centurion’s fees are $500 to $800 a day. But what these courses don’t offer is much—or any—training on how to deflect or, at worst, come to terms with sexual assault. AKE takes female journalists aside for a live video chat with a female representative to address rape and sexual assault; Centurion will offer “extended closed sessions about rape and sexual assault for female journalists if wanted,” according to Carole Rees, the company’s business development manager. Since the attack on Logan, she says, there have been a lot of inquiries as to whether sexual and gender-based violence is offered in Centurion’s hostile environment training. However, according to “Unspoken,” the BBC, which Matloff calls “a pioneer in trauma awareness,” is the “only major news organization that offers special safety instruction for women, taught by women.”

This omission isn’t always the trainers’ fault, according to Matloff. Since the responsibility is on the employer to request any specific training, she says, “We can’t blame Centurion and AKE for not offering it if it wasn’t requested.” Scott White, CP’s editor-in-chief, for example, did not ask for any specialized sexual assault training beyond the regular hostile environment courses before sending his reporters to Afghanistan. The female reporters who covered that war encountered dangerous situations, but he says, “I don’t think they encountered them because they were female.” CP’s Stephanie Levitz, who did two rotations in Afghanistan, is dubious about what specialized training would look like. Is it “How not to get sexually assaulted?” she asks. “That’s impossible.”

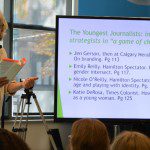

But Matloff disagrees. She is one of the primary organizers of a new course, Reporting in Crisis Zones, recently launched by the continuing education department of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Specifically designed to fill the gaps in training journalists receive elsewhere, with an emphasis on conflicts and “avoiding unnecessary peril,” it first ran last November. Topics in the first two days included cybersecurity, risk assessment, situational awareness, dealing with emotional trauma and emergency first aid. But the third day, open only to women, addressed rape and assault prevention (the pilot version of the course cost $795 for the first two days and $895 for all three days). “The goal is to provide rape prevention training for foreign correspondents so that they can avoid situations like Lara Logan’s, and better cope should the unmentionable occur,” Matloff says. The website lists delay tactics, basic self-defence and healing as part of the third day’s curriculum. Matloff explains the reasoning behind this specialized instruction: “[A]s we saw with this horrible incident with Lara Logan, where her male colleagues were beaten, she was beaten and sexually assaulted.”

Obviously passionate about the issue of women’s safety and the need for addressing the issue of sexual assault, Matloff recalls a friend who was raped while on foreign assignment but felt too uncomfortable to tell her editor. Fearing that she might have contracted AIDS, the reporter told a convoluted cover story to her boss so she could leave the country where she was stationed and then spent a fortune on anti-retroviral drugs in another country. Had she divulged the rape, her employer could have covered her expenses. “I never want to see that happening to another colleague,” Matloff says with conviction.

CP’s White calls the fledgling course “a welcome and needed addition to this type of training.” Although CP has no immediate plans to send any staff into conflict zones, White says he would consider the program in the future. And Colin MacKenzie, the Star’s political editor, says, “The rape-prevention module is overdue.”

Still, some female reporters aren’t sold on the Columbia course. Medina is skeptical about the program’s aim to teach participants how to work effectively and safely in volatile situations. “The only way to do that,” she says, “is to not work effectively or to stay home.” She’s also wary about attention given to the threat of sexual assault: “The more the academics and media and articles, perhaps, such as this [story], talk about rape and sexual assault, the more journalists will fear it,” says Medina. “If you go into a situation wearing that fear, you can invite it.”

Meanwhile, Corinna Schuler, a former Post correspondent who served in Africa, believes the course is not practical “for people who are already working as full-time reporters,” partly because when a journalist is in the field, a lot comes “down to instinct and learning on the job, on the fly.” And Stephanie Nolen says, “I think it’s really dangerous to frame this as a conversation about the vulnerability of women in this job when I don’t think women are any more vulnerable than men,” although she concedes women may sometimes be “differently vulnerable.”

One reporter who does believe Matloff’s program could teach her something new and valuable is Sonia Verma. She notes that when she did training in Kingston, Ontario, about 10 years ago, she was only one of three women in a class of about 20, so she didn’t think specific training for women made sense in that context. (She does recall that the instructor did mention sexual violence, but it was regarding male journalists being raped in Mogadishu.) Verma thinks the Lara Logan incident is a wake-up call for the industry. “There isn’t really specific training for women—the unique situations that women might find themselves in,” she says. “The question should be how can we better equip women to do their jobs.”

by Ruane Remy

Ruane Remy was the Chief Copy Editor of the Winter 2012 issue for the Ryerson Review of Journalism.